Invisible Men – Guest Post by Shawn Hamilton

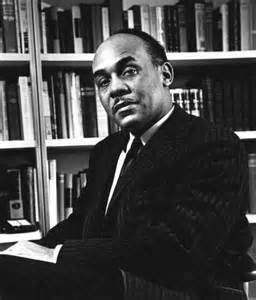

In his seminal works –Shadow and Act and The Invisible Man–Ralph Ellison created two metaphors that speak to one of America’s great dilemmas regarding African Americans: how do Americans reconcile their beliefs in ‘democracy’with certain ‘anti-democratic’practices? The first appears in Shadow and Act, a book of essays, in which Ellison describes the African American as a Giant upon whom all of American history ‘unfolds’, a ‘human natural resource’that must be restrained to preserve national power and stereotyped to preserve national innocence.[1] The second metaphor, the ‘battle royal’, appears in an earlier work The Invisible Man which explores what happens when the metaphorical giant attempts to break the chains and shape its destiny.[2] While both metaphors spoke explicitly to slavery and Jim Crow, they echo today in a variety of American institutions, the most ironic and obvious example is Big Time College Sports.

College sports is a multi-billion dollar industry with most of its revenue being created by two sports –football and basketball. So, a top football recruit is worth an additional $500k and a top basketball recruit is worth an additional $1.5 million to their respective programs.[3] The players in these sports are predominately black and get a very small portion of the wealth that they create. In the era of the student entrepreneur –Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, et al –is a bit ‘peculiar’to say the least. Our society has no problem with students profiting from their work in theory or principle, unless it involves this small group of people euphemistically labeled ‘student athletes’.

In the essay 20th Century Fiction and the Black Mask of Humanity in Shadow and Act, Ellison attempts to explain the absence of black humanity in the popular fiction of his day. Blacks were either caricatures or completely absent. To understand this dynamic, Ellison argued that the Negro should be thought of as a Giant, a bit like Gulliver’s. As long as the Giant accepted restraints and continued to provide sustenance he was not a problem. However, emancipation and the years leading up to Reconstruction gave the Giant the opportunity to exercise its will: politically, economically and also psychologically. Blacks began voting, owning property, and shaping culture. This created the need for not only countermeasures like political and economic disenfranchisement but also stereotypes to justify those countermeasures. The black would be recast as a brute that needed be monitored for the benefit of the public or a child that needed to be supervised for the benefit of  himself.

himself.

The Giant in college sports is the black athlete and he encounters similar forces. Every dimension of college sports is reframed to make the exploitation of the athlete possible, profitable and seemingly necessary for the athlete’s own betterment. The coach is recast as a kind of missionary saving wayward young men from the perils of the ghetto rather than an extremely well compensated employee. The university is re-imagined as a neutral, even reluctant, participant in sports rather than the beneficiary of free labor worth tens of millions of dollars. The NCAA is reframed as an objective enforcement organization rather than a cartel that controls college sports for a profit. Boosters are recast as an outside contagion rather than key contributors to and beneficiaries of college sports. Education itself is redefined and reshaped to fit the needs of the college sports industry, not the actual athletes. And of course the athletes themselves, black athletes in particular, are recast as young men in desperate need of control or protection. The athlete then signs away his privacy, economic freedoms, personal likeness, and potentially his health, for the longshot chance of becoming a professional athlete or the ‘opportunity’to get an education. When the athlete challenges the exploitation and paternalism of this arrangement –when the Giant pulls at his restraints –he is reminded of the Faustian bargain he has made in trading inequality for ‘opportunity’. Ellison explores this dynamic in the battle royal scene in The Invisible Man.

The Invisible Man chronicles the life of an unnamed protagonist struggling to survive in a world that refuses to acknowledge his equality, humanity and seemingly his very existence. The protagonist, a high school valedictorian, is invited to deliver his graduation speech to a gathering of white community leaders, but before he can deliver the speech he must participate in a cage brawl with a group of other young black men. The scene reads like a lurid, fever dream. The young men are goaded with liquor. They are tempted by a gyrating white stripper. Then after the initial brawl, they must again fight one another for money on an electrified carpet. When this is over, beaten and bloodied, our protagonist is given an opportunity to deliver his speech on black ‘responsibility’–and that is when the trouble starts. In his subconscious or perhaps conscious mind, he wants to lay claim to black equality, so during the speech he lapses and rather than arguing for ‘black responsibility’a vague trope, he argues for ‘black equality’infuriating his audience. When they express their outrage he quickly corrects himself, profusely apologizing. His reward is a scholarship to a local Negro college. The price of progress is brutalization, inequality, and paternalism.

Similarities between Ellison’s battle royal and college sports abound. Football has become increasingly violent over the years, particularly the seasoning process that the rookie undergoes to win the respect of experienced players. Myron Rolle, a former FSU player and Rhodes Scholar, describes his own team’s tradition of making rookie players box veteran players at the end of practice to prove their toughness. The recruiting process also mirrors Ellison’s battle royal in some interesting ways. Many schools have ‘recruiting hostesses’attractive young women who throw parties for prospective recruits plying them with food, attention, and at the University of Tennessee lots of ‘eye contact and touching’.[4] The lure of financial reward and subsequent punishment is ever present. Booster clubs, closely affiliated with the schools, pay for access to the games and the athletes often giving them jobs or money. All of the actors in this farce are there because of the athlete, but if the athlete pursues a reward commensurate with his contribution –if he demands equality –he is condemned, demonized and expelled.

Ellison, himself a varsity football player, would often sit perched in his window and watch young men play basketball on the court below his apartment building.[5] For Ellison, watching the young men play was like peering into both the past and the future. Would the young men’s abilities be considered a ‘gift’that represented an entitlement for someone else? Or would they be an asset for which they are due the rewards? The past had established a model about which Ellison had written extensively, but perhaps the future would be different. However, in transforming the athlete into a person whose ability is maximized for the sake of profit, but minimized for the sake of power, college sports grafts the worst of the past onto the present and answers Ellison’s questions in truly disturbing ways.

Shawn Hamilton is a NJ based blogger and filmmaker. He is currently producing a documentary called ‘Game Theory: Caste, Cartels, and College Sports’that looks critically at college sports as a body of institutions and ideas. He blogs at www.duelinginterests.com about politics, pop culture, current events and history. He is a graduate of Hampton University.

[1] Ellison, Ralph, and John F. Callahan. The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison. Modern Library ed. New York: Modern Library, 1995. 85.

[2] Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. 2nd Vintage International ed. New York: Vintage International, 1995. 17-35.

[3] Clotfelter, Charles T. Big-time Sports in American Universities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011. 118.

[4] Clotfelter 120

[5] Ellison and Callahan 385

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I really like the idea of applying Ellison’s ideas to NCAA athletics. It was inspired. I wonder if the analysis could get even more specific. I was thinking that part of what makes the “battle royal” scene so disturbing has to do with how the white men in the scene deal with black bodies. As mentioned, the boys are first made to watch a “magnificent blonde” exotic dancer before they fight one another blindfolded in the ring (another in a riot of Ellisonian ocular tropes in the novel). The boys are both terrified and aroused at the same time. They’re faced with the central taboo of white Southern racism: the white female body juxtaposed with black male virility. One boy has to hide his arousal. Some of the white men threaten them while others encourage them. They don’t know whether to look or look away. (The protagonist decides to look.) So they’re aroused and then made to fight one another for the entertainment of the white men. It’s a mixture of white male desire for black bodies and lust for absolute and arbitrary control of those bodies. The white woman in the scene, in this case the dancer, is a victim too. She’s nearly raped by the crowd of drunken men. Rather than the sacred, marriageable white woman of Southern white supremacist shibboleth, she’s presumably “fallen” and so also an object of their basest desires (a proxy or a fantasy for what they’d really like to do to those white women they’ve set on pedestals). By now it’s clear how this applies to the dynamics of any number of college and professional athletic contests: presumably hyper-masculine white male watchers of black male bodies in motion, objects of desire and control, the entertainment accompanied by the debasement of a certain kind of white female body and so on. The twist, of course, in the novel is that the boys are blindfolded, so jealousy of black physical prowess is made less of a problem in the ritual and instead the white men get to indulge fantasies of total (arbitrary) control and power. As the protagonist puts it, “I was without dignity.” By the time the protagonist gets to his speech, it’s pretty clear that anything resembling the imposition of black intelligence doesn’t belong in the ritual. (“He knows more words than a pocket-sized dictionary!” jokes one of the white men.)What makes the whole thing even more powerful and horrifying is that it’s also darkly comic. The protagonist is going through something unfathomably terrifying and yet he continues, over and over again, to hope that the men will like his speech. From his retrospective view, the narrator notes it: “What powers of endurance I had during those days! What enthusiasm! What a belief in the rightness of things!” He’s a Candide figure, a naif, which makes it all even more painful. The implications are more than a little disturbing and deeply problematic for college athletics.

Never thought about college sports in this manner. Thanks for the added knowledge bro.