Most commercially successful biblical epics have been films based on the Old Testament. Such “swords and sandals” films tend to attract viewers because the Old Testament is full of stories well suited to the big screen. Hollywood likes its unambiguously good-versus-evil narratives, particularly when they include sword battles and swarms of locusts.

Most commercially successful biblical epics have been films based on the Old Testament. Such “swords and sandals” films tend to attract viewers because the Old Testament is full of stories well suited to the big screen. Hollywood likes its unambiguously good-versus-evil narratives, particularly when they include sword battles and swarms of locusts.

So Ridley Scott’s new film Exodus: Gods and Kings, in theaters nationwide this Friday, is bound to fill theaters. Even a few early negative reviews shouldn’t dissuade viewers eager to see Christian Bale as (White) Moses, whom Bale describes as “schizophrenic” and “one of the most barbaric individuals that I ever read about in my life.” Scott Mendelson of Forbes writes: “Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods and Kings is a terrible film.” And Alonso Duralde of The Wrap pans: “If you’re going into Exodus: Gods and Kings thinking that director Ridley Scott is going to give the Moses story anything we didn’t already get from Cecil B. DeMille in two versions of The Ten Commandments, prepare to be disappointed.”

But surely these Debbie Downers can’t compete for attention with a trailer like this:

Whoa! Manly manliness!

Speaking of manly manliness, I suspect gender normativity is a key factor as to why the Old Testament has typically worked better than the New Testament on the big screen. It is more difficult to portray Jesus as a normative male. He is a caregiver. He is celibate. He is anti-moneychanger. Red-blooded American men are none of these things. Mel Gibson worked overtime to make the Jesus of his bloodthirsty 2004 film The Passion of the Christ a manly man through extreme sacrifice.  As Rhonda Hammer and Douglas Kellner write:

As Rhonda Hammer and Douglas Kellner write:

The representation of the strong and stoic Jesus, manly enough to be beaten to a pulp with nary a whimper, is reminiscent of Clint Eastwood’s “Man With No Name” in Sergio Leone’s “spaghetti Westerns” and his own 1973 film High Plains Drifter. The ultramacho bearer of unimaginable violence and torture is also evocative of the Rambo figure and many of Mel Gibson’s previous action adventure heroes, such as the stalwart Braveheart (1995) in which Gibson’s William Wallace character is virtually crucified at the end of the film, or any number of other Gibson figures in films like Ransom, Payback, or The Patriot, who are badly beaten, but ultimately redeemed.

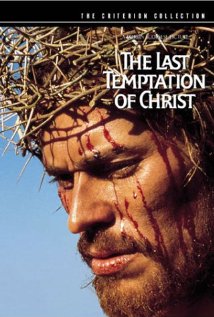

In contrast, Martin Scorsese’s interpretation of Jesus, as played by Willem Dafoe in the controversial 1988 film, The Last Temptation of Christ, seems much less capable of taking a beating or making other manly sacrifices. Scorsese’s Jesus is a gender freak, at least by the standards of the biblical epic, not to mention by the standards of American manhood. Scorsese’s Jesus often seems weak-willed. This is why a stronger, manlier Judas—played by the nothing-if-not manly Harvey Keitel—is the hero of the film. Judas whips Jesus into shape, keeps him on his mission, and scolds him into making the ultimate sacrifice. Conservative media activist Donald Wildmon accused Scorsese of making a film that “portrays the Lord Jesus Christ as a liar, a fornicator and a weak, confused, fearful individual unsure of who he is.” In this way critics of the film made even Jesus’s heterosexual desires seem effeminate.

In contrast, Martin Scorsese’s interpretation of Jesus, as played by Willem Dafoe in the controversial 1988 film, The Last Temptation of Christ, seems much less capable of taking a beating or making other manly sacrifices. Scorsese’s Jesus is a gender freak, at least by the standards of the biblical epic, not to mention by the standards of American manhood. Scorsese’s Jesus often seems weak-willed. This is why a stronger, manlier Judas—played by the nothing-if-not manly Harvey Keitel—is the hero of the film. Judas whips Jesus into shape, keeps him on his mission, and scolds him into making the ultimate sacrifice. Conservative media activist Donald Wildmon accused Scorsese of making a film that “portrays the Lord Jesus Christ as a liar, a fornicator and a weak, confused, fearful individual unsure of who he is.” In this way critics of the film made even Jesus’s heterosexual desires seem effeminate.

So although Scorsese’s portrayal of Jesus as a sex-starved, well, man was the main focus of right-wing criticism—William Buckley complained that Scorsese gave “us a Christ whose mind is distracted by lechery, fancying himself not the celibate of history, but the swinger in the arms of the prostitute Mary Magdalene” * —the fact that Jesus did not easily overcome such sexual temptations made him seem like less of a man. And this is part of why The Last Temptation generated such widespread cognitive dissonance: it disrupted the gender norms that help define the biblical epic genre. In this way and a whole lot more, it is the quintessential biblical anti-epic.

So although Scorsese’s portrayal of Jesus as a sex-starved, well, man was the main focus of right-wing criticism—William Buckley complained that Scorsese gave “us a Christ whose mind is distracted by lechery, fancying himself not the celibate of history, but the swinger in the arms of the prostitute Mary Magdalene” * —the fact that Jesus did not easily overcome such sexual temptations made him seem like less of a man. And this is part of why The Last Temptation generated such widespread cognitive dissonance: it disrupted the gender norms that help define the biblical epic genre. In this way and a whole lot more, it is the quintessential biblical anti-epic.

* The way the film emphasized Jesus’s human side did not track with longstanding traditional and conservative readings of the Bible, and is why it largely angered the Christian Right, making it and its reception one of the landmarks of the culture wars. For more details on the controversy, you’ll have to wait and read my book—which will be out in April, hallelujah! Or for the impatient among you, read Thomas Lindlof’s superb and thorough book, Hollywood Under Siege: Martin Scorsese, the Religious Right, and the Culture Wars, which has been my most important source for understanding The Last Temptation as a culture wars phenomenon.

* The way the film emphasized Jesus’s human side did not track with longstanding traditional and conservative readings of the Bible, and is why it largely angered the Christian Right, making it and its reception one of the landmarks of the culture wars. For more details on the controversy, you’ll have to wait and read my book—which will be out in April, hallelujah! Or for the impatient among you, read Thomas Lindlof’s superb and thorough book, Hollywood Under Siege: Martin Scorsese, the Religious Right, and the Culture Wars, which has been my most important source for understanding The Last Temptation as a culture wars phenomenon.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Andrew, this is great.

So many ideas running through my head on this (and I maybe ought to keep most of them there at present!).

I think the charge of “effeminacy” or unmanliness by the film’s detractors is interesting, especially given the nature (and delightful depiction) of that “last temptation.” In any other movie, the most controversial scenes in the film’s fantasy sequence would be a marker of manliness. Here they’re (bizarrely) taken as a sign of effeminacy.

I am all too familiar with the tendencies of late 20th century pop-protestant/ad hoc/fundamentalist Christology, and I’m going to try to just let that mess alone. But it is fascinating that this Jesus was damned if he did, and damned if he didn’t — his very susceptibility to temptation was seen as an affront to the notion of Christ’s sinlessness, and his struggle against/resistance to temptation was seen as a sign of weakness rather than a sign of strength.

On the whole matter of popular theology, it’s my understanding that before the film made news, Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel used to be available in independent Christian bookstores. In response to the controversy over Scorsese’s adaptation — a controversy ginned up by plenty of people who never read the book, never saw the film, and never planned to see it (of course) — Christian booksellers pulled the copies from their shelves. (I know this only via anecdote; no archival corroboration.)

For me, as filmic depictions of Jesus go, I’m torn between Last Temptation and Jesus Christ Superstar. Though both these films are different, they do push the envelope on Jesus/Mary Magdalene/disciples along somewhat similar lines. Of course there’s the whole Jesus people / hippie / rock opera thing going on too.

In any case, both the portrayals show a Jesus acutely aware of the goodness and the griefs of embodiment. Beyond the kind of under-theorized (or just idiosyncratically theorized) theological conceptions of the personhood of Christ that seemed to take various implications of a human nature off the radar screen for a lot of people — and those conceptions are no small thing — I’m wondering what other ideas or notions might have gotten mixed up in the fraught discourse of masculinity to make this grittily human portrayal so objectionable at that particular time. (And then fast forward to Mel Gibson, and people can’t get enough of embodiment.)

I do think it’s worth pointing out that Evangelical Christians did finally have a “canonical” portrayal of Jesus in the 1979 film Jesus — popularly known as “the Jesus film” and very widely used in Protestant missionary outreach to this day. Maybe Lindlof covers this in his book? In any case, that Jesus is a lot more conventional than either Neeley’s or Dafoe’s.

Really enjoyed this, and I’m looking forward to reading more about the controversy in your book!

Unless this will mean providing some spoilers (of your book, not the film–I’m assuming everyone knows how it ends), I’m wondering if you could say a little about how Scorsese’s reputation as a director contributed to the film’s reception? There was, as you say, a cognitive dissonance between the generic conventions of the biblical epic and TLTOC, but there must also have been a cognitive dissonance between the expectations many people might have had about what Scorsese’s Jesus would look like (robust, tough, maybe crazy) and what viewers got, right? Unless the novel’s content was well-known enough to give potential critics a sense of what was coming?

Thanks for the comments, LD and Andy. I’m looking forward to your contributions to biblical epic week. (LD, by the way, has already contributed in a way, off site at her personal blog, with her remarkable and hilarious essay about Moses’s foreskin, or something like that.)

LD: I agree that charges of effeminacy leveled against Dafoe as Jesus as channeled through Scorsese were weird and contradictory given that the dream sequence at the end of the film–“the last temptation”–is full of Jesus having sex, getting married, making a family, things that men are normally supposed to do. But weirdly, the Christian Right version of manliness for Jesus was him being resolute in not succumbing to temptation–it was him suffering mightily for us, him gushing blood for us (as Mel Gibson envisioned). The fact that Jesus ultimately does not succumb in The Last Temptation is ignored of course. The fact that Scorsese dwelled on Jesus dreaming of temptation was enough to render the Christian Right apoplectic, for a whole host of reasons, one of which is found in gender expectations. In my book I do not dwell on the gendered aspects of this, and have only made these connections more recently, but hope to write more about them at some point.

I’m not sure how American Christians read Kazantzakis’s novel in the years proximately preceding the film’s release. When the novel was first translated into English in the early 60s, it was banned on many libraries for many of the same reasons the filmic version was later rejected: because it presented Jesus as too human, not divine enough. Kazantzakis’s novel was popular in the sixties for the same reason as existentialism was so widely read in American culture at the time–Kazantzakis’s Jesus was searching out his humanness.

Answers to your questions about embodiment may have to wait. Or other readers should chime in!

Andy: Scorsese’s reputation as a director is the only reason the film was made. Paramount backed out of its contract to produce it in 1983 as filming was set to take place, and most other studios wouldn’t touch the script, because conservative groups were already mobilized against it. But Universal wanted to sign Scorsese up to a multi-picture deal due to his past successes, and Scorsese made clear he was open to such an agreement as long as Universal would allow him to make Last Temptation.

In terms of Scorsese’s reputation relative to the reception of the film, not much was said about that in relation to his portrayal of Jesus. Much more, though, was said about how Scorsese’s apostles seemed stolen from the mean streets of New York, accent and all. I mean, Harvey Keitel as Judas! So this is just another layer to add to the weird complexities of gender at work in the film, and the even weirder gendered responses to the film.

(I won’t share more because I do want people to read my book! Or you can read Lindlof–he deals with all of this.)

A lot of weird in that comment.

Andrew, thanks for the reply, and for linking to my post. (As you well know, my blog post is an appreciation of the illustrations in a children’s Bible story book, and how they depict masculine embodiment!)

But, yes, embodiment — a problematic enough issue in the history of Christian theology in the abstract, but made peculiarly concrete by actors in these roles. And, as Ed Blum and Paul Harvey remind us in Color of Christ, Jesus in Hollywood is very, very white (though “white Jesus” was certainly not invented by Hollywood, he has been “immortalized” as such on film.)

It seems to me that no filmic portrayal of Biblical narrative can ever be “authentic” — but what these different portrayals authorize can do some authentically powerful cultural/ideological work.

And I too hope (and fully expect) that people will read your book!

If we’re going to talk of a manly, American Jesus, surely we should mention Bruce Barton and The Man Nobody Knows (1925), which was in large measure an attempt to reimagine Jesus so that he might conform to 1920s middle-class American ideas of manhood and business success. In the book’s introduction, Barton explains (writing about himself in the third person) that, as a child, he felt that Jesus was “sissified” compared to the heroes of the Old Testament, but that as the years passed he came to realize that Jesus was just misunderstood and the historical Jesus was all things Barton would want a man to be:

Has anything like Bruce Barton’s version of Jesus ever made it to the silver screen?

I think you could make an argument that Gibson’s “superhuman endurance Jesus” (outlined in my post) fulfills at least one part of Barton’s wish for an on-screen revision. – TL