Editor's Note

This interview is the first in a two week Salon on Dr. Blain’s book Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle With Freedom.

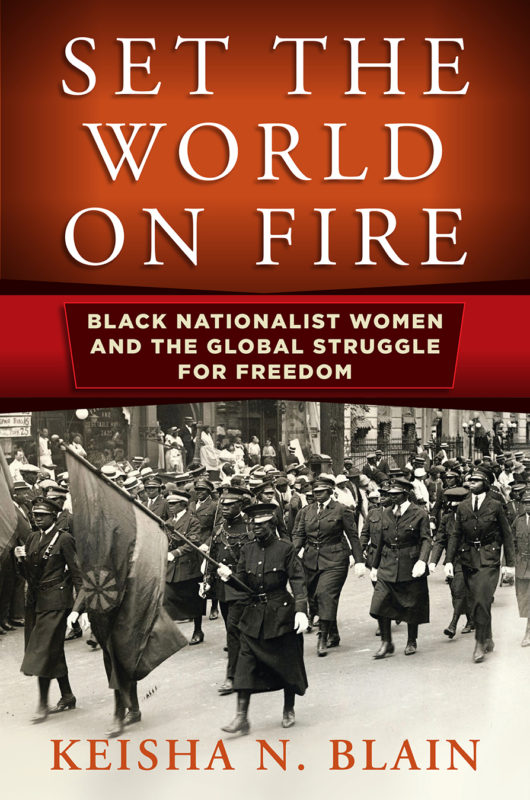

Keisha N. Blain is an award-winning historian who writes on race, politics, and gender. She obtained a PhD in History from Princeton University and currently teaches history at the University of Pittsburgh. She is the author of Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and co-editor of Charleston Syllabus: Readings on Race, Racism and Racial Violence (University of Georgia Press, 2016); and New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition (Northwestern University Press, 2018). Her work has been published in several academic journals such as the Journal of Social History and Souls; and popular outlets including the Huffington Post, The Washington Post, and The Feminist Wire. She is the president of the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS) and senior editor of its popular blog, Black Perspectives.

An Interview with Keisha N. Blain

An Interview with Keisha N. Blain

Holly Genovese: How did you come to your topic? As a graduate student I have been thinking a lot about how we come to and shape our choices of topics. Was this what you had originally planned to write about it?

Keisha N. Blain: As an undergraduate student, I wrote a research paper on women in the Garvey movement of the 1920s. I eventually expanded the paper into an honors thesis, and even published two articles on the topic. I wanted to write a dissertation on women in the Garvey movement, but a few mentors advised against it because several scholars were already working on the topic. The irony is that I ultimately found myself right back to where I started—and I think it was fate. During my first year of graduate school, I reached out to several archivists and librarians to ask for leads on collections that might shed some light on black women’s internationalist activities. One archivist at Duke University suggested that I look at a collection that included letters from Mittie Maude Lena Gordon. I quickly planned a trip to Durham and the rest is history so to speak. I was determined to find out more about this fascinating black woman and her organization, the Peace Movement of Ethiopia. I was (pleasantly) surprised to find out that she had been active in the Garvey movement and I started to see a story unfold before me. I took my first attempt at articulating my ideas in a paper I wrote for a graduate seminar with Tera Hunter, my dissertation

advisor. Hunter shared my excitement and encouraged me to pursue the topic further. With her support, as well as the other members of my committee, I completed a dissertation that examined black nationalist women’s national and global politics from 1929 to 1945.

HG: Was this your dissertation? If so, could you talk about that process of converting it to a book?Is it largely the same?

KNB: Set the World on Fire is certainly an outgrowth of my dissertation, but I made significant changes to it. These included refining my arguments; revising (and in some cases, rewriting) the chapters; extending the chronology; adding new historical figures; and integrating new primary and secondary sources. I also removed a chapter that simply did not fit, and I changed the structure of the narrative from a thematical

approach to a chronological one. The process of revising began immediately following my defense. Naturally, dissertation defenses ignite feelings of anxiety and stress, but they are more than a rite of passage; I think they are especially useful for helping scholars identify the gaps in their knowledge as well as the areas of weaknesses in their projects. Immediately after the defense, I made a list of things I needed to address in the book and I spent considerable time thinking about how I would craft the book differently so that it would be significantly better than the dissertation. A year-long postdoctoral research fellowship (without teaching obligations) gave me time to revise the dissertation into a book. During this period, I found it helpful to secure a new set of readers who had no attachment to the project and even a few readers who had no attachment to me personally. This sometimes meant reaching out to scholars I admired but didn’t know well to ask if they would read a chapter or two and offer honest feedback. In one case, a very generous senior scholar read the entire dissertation and we later spent hours discussing its strengths and limitations. Surprisingly, my experience on the job market also helped—I was fortunate to have several interviews and campus visits and those were unique opportunities for me to discuss my project with others who had a chance to read the dissertation. The questions they asked helped me refine my ideas (and better articulate them) and I think those kinds of experiences made the process of revising a smoother one. And finally, I found great advice and strategies in William Germano’s From Dissertation to Book.

HG: Your book fits into a broader discussion in intellectual history, and particularly in African American intellectual history, about expanding the nature of who we categorize as an intellectual. Did you receive pushback?

KNB: I received some pushback. I vividly remember giving a talk about my project while I was still ABD and on the job market. I was so excited to discuss the project before a group of a historians I respected. Immediately following the talk, one senior scholar started questioning me about the work in a very combative tone. He took issue with my decision to frame the women as intellectuals and did not shy away from letting me know that these women were not ‘theorists’ as I suggested. Activists, yes. But not theorists. Karl Marx was a theorist, he went on to argue, but not “these women.” He ultimately accused me of trying to “exaggerate the importance” of my historical subjects. It was a difficult experience, but it was evidence that I was going against the status quo and in so doing, I was making some people feel uncomfortable. I knew then and there that it would be a long road ahead and I would likely encounter the same resistance throughout my career. However, I firmly believe that no one group has a monopoly on the term “intellectual” (or theorist). More importantly, I think we do a disservice to the history when we fail to acknowledge the range and diversity of individuals who shaped national and international thought.

HG: You write about such dynamic women and activists with interesting histories! How did you find them? Did you have a favorite (or favorite part to write?)

KNB: The process of finding these women’s stories was very difficult—it required a lot of digging and certainly a lot of traveling to piece the story together. I tried to make good use of an array of primary sources, including archival materials, historical newspapers, census records, government records, oral histories, songs, and poetry. I analyzed these sources with a fine-tooth comb, looking for clues and bits of information to help me craft the narrative. I think Mittie Maude Lena Gordon is my favorite—not because I

agree with everything she believed, but because she left such a robust trail of material that allowed me to develop an in-depth understanding of her ideas. I got to know her well—as well as a historian can get to know a historical figure without ever getting a chance to meet them. Although I often disagreed with her approaches, I grew to understand them.

HG: What do you hope people take away and learn from the book?

KNB: My hope is that people will read this book and learn something new. I certainly learned a lot in the process of writing it. I also hope that people will develop a better sense of how black women, particularly members of the working poor and individuals with limited formal education, have functioned as key leaders, theorists, and strategists in US and global history. I hope these women’s stories will broaden readers’ understanding of American and global politics by challenging the neat frameworks that so often dominate mainstream historical narratives.

0