I had the pleasure of viewing the film Interstellar this week with a few fellow history graduate students. To say that the film left us with plenty of questions would, well, be an understatement. But today’s post will only make cursory remarks on the ending. Other reviews have talked about the American hero and Interstellar or how gender is an important part of the film. What I’m much more intrigued by is the vision of the United States of America as presented in Interstellar. Suffice to stay, spoilers follow—so you were warned.

Interstellar is filled with callbacks to the past—more often than not, a uniquely American view of the past. That past is never divorced from the America portrayed in the film. A broken, dirty, dusty nation, the United States of the future suffers with the rest of the world from a condition called the Blight. Destroying crops and humanity’s food supplies, the Blight has created a world of suffering and starvation, ridding the world of the need for armies or navies. After all, Interstellar suggests, who has time for war when everyone is afraid of starvation? Interviews from Ken Burns’ The Dust Bowl are interspersed through the film, at times disorienting the viewer as to whether or not the elderly interviewees are talking about humanity’s grappling with The Blight in the film or if they are, in fact, talking about the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. I suspected while viewing the film that we were, in fact, watching the latter. However, that twisting of the past with the future did not prepare me for a scene early on in the film which showed how even history itself has changed to adopt to a depressing future.

a depressing future.

When Cooper’s (Matthew McConaughey) daughter, Murphy, has a parent-teacher conference, he is stunned to find out what she is being taught in schools. According to “updated” textbooks, the Apollo landings were faked to trick the Soviets into believing the United States had won the Space Race. It would not do, in other words, for people in the Blight-riddled present to believe that the United States, at one point, had a robust space program—and, by extension, spent billions of dollars in the stars and not on Earth. And Murphy’s teacher not only teaches this as fact but, as far as I could tell, believes

the narrative the new textbooks offer. Cooper, a former member of NASA (an organization that, by the start of the film, most Americans have been led to believe is no more) is of course not happy about this.[1]

I suppose there’s a silver lining to this—it shows that, even in a future where humanity faces destruction, there’ll be a place for historians (a point I shall come back to at the end of my review). It’s not quite the apocalypse of 2012, but the end of the world as portrayed here is nearly biblical in scope. The Blight isn’t an attack of locusts sent by God—at least, that’s not explicitly stated in the film. But a sense of the unknown, of the sublime comes through in many of the scenes set off Earth. Meanwhile, a greater force is thanked for the appearance of a wormhole near Saturn, which might be humanity’s salvation—the beings referred to merely as “They.”

Still, as much of a science fiction fan as I am, and as thrilled as I was by the portrayal of space travel and strange planets in the movie, I was more often intrigued by Interstellar’s portrayal of America. The space program, as mentioned before, has been publicly starved of funds. Farming, and not engineering, is seen as the most needed skill at the moment (perhaps a slight commentary on the current focus on STEM fields—can’t get at a more basic, or necessary, STEM field than farming). Connor laments over and over how Americans have given up on exploring. His father (played by John Lithgow) even tells him that he was born forty years too late—or, in a brief but noticeable moment of optimism, forty years too early.

To make a long story short, Connor and Murphy stumble upon America’s answer to the Blight: a Hail Mary space mission to save humanity. Or, perhaps, to merely save the United States? One element of the film that puzzled me was how the United States was able to take on the awesome mission of sending ships to Saturn and through a wormhole and to planets in a distant galaxy—without any help from the rest of the world. I love seeing America win in the movies. But I was a bit incredulous—how the heck can the USA get this project off the ground in the future when the space program of today is so weak?[2] And, yes, it’s just a movie. But there’s a history of science fiction stories where the US joins with other nations to solve problems in space.

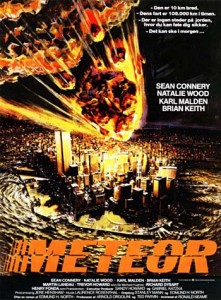

Films such as the, ahem, “classic” 1979 movie Meteor

show the United States working with the Soviet Union to deflect a meteor heading towards Earth. Deep Impact (1998) also showed the US and Russia working together to destroy a comet heading  towards Earth. The more bombastic Armageddon, also released in the summer of 1998, barely featured the Russians at all. They merely came into the film as comic relief with the destruction of the MIR space station—although it’s worth pointing out the Russian Cosmonaut who comes along for the ride in that film does become a hero by the end of the movie. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, the 1990s television series Space: Above and Beyond has humanity fighting an alien invasion with Earth’s various militaries retaining their uniforms, but with the United States very much leading the way. With the exception of Jean-Luc Picard, the captains of the various Star Trek series have been Americans—but all working as members of Starfleet, the exploration and military arm of the United Federation of Planets.[3]

towards Earth. The more bombastic Armageddon, also released in the summer of 1998, barely featured the Russians at all. They merely came into the film as comic relief with the destruction of the MIR space station—although it’s worth pointing out the Russian Cosmonaut who comes along for the ride in that film does become a hero by the end of the movie. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, the 1990s television series Space: Above and Beyond has humanity fighting an alien invasion with Earth’s various militaries retaining their uniforms, but with the United States very much leading the way. With the exception of Jean-Luc Picard, the captains of the various Star Trek series have been Americans—but all working as members of Starfleet, the exploration and military arm of the United Federation of Planets.[3]

In short, America’s place in the world is often reflected in how America sees itself in science fiction. This summer’s Edge of Tomorrow portrayed the US and our European allies about to storm the beaches of Northern France to liberate Western Europe from an adversary of unimaginable power—sound familiar? Edge of Tomorrow shares with Interstellar a nostalgia for the past—a uniquely American past in which we were powerful and either led the way (as in D-Day) or operated on our own to explore the stars (as in the case of the Apollo missions, which we’re supposed to see as fake by the time of Interstellar

). Today we want to uphold America in science fiction precisely to deal with the fears facing the American people in the real world.

As an example, the idea of Hollywood reflecting the fears and hopes of America is explored by English professor Paul A. Cantor in his book The Invisible Hand in Popular Culture (2012).[4] A sense that America can win is seen in Interstellar—especially when you notice the American flag flying on planets in another galaxy.[5] But, at the same time, a fear of government secrecy is at the heart of Interstellar. First, the secrecy behind the Lazarus missions; second, the bigger secret—that there is probably no hope for the people of Earth, and humanity may only continue thanks to test tubes and incubation units.

But “They” save humanity—a “They” which turns out might just be human beings on a different plane of existence, far in the future.[6] And here there’s still more hope for historians—at the least, historic preservationists and public historians have a future in transporting the home of Connor and Murphy to a space station, and explaining it to tourists in the future. History—a story of America as one of ultimate triumph through exploration—serves as the backbone of Interstellar. It’s no surprise such a film comes out today, with fears about America’s place in the world buttressed by a space program

struggling for funding and concern over climate change becoming a serious political issue.

For the last week the blog has discussed Biblical Epics. The science fiction epic—films such as Interstellar or Star Wars—say as much about the mind, and the soul, of America as those epic films set deep in humanity’s past.

[1] Of course, this doesn’t even get at the fact that during the late 1960s, the American people were far more ambivalent about the Apollo missions than popular memory portrays. See No Requiem for the Space Race by Matthew Tribbe.

[2] Thinking about this more, a line from the parent-teacher scene sticks out. Connor says to the principal, and I’m paraphrasing from memory, “Where are my tax dollars going? There’s no more armies.” Perhaps all the money that once went to America’s armed forces is being funneled, secretly, to this renewed NASA effort.

[3] And yes, I know Captain Picard says repeatedly that Starfleet isn’t the military. But when the Federation is attacked…who picks up the slack?

[4] Paul A. Cantor. The Invisible Hand in Popular Culture. (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012) Full disclosure: I reviewed this book for the Journal of Popular Culture in 2013.

[5] I’d be lying if I didn’t say seeing the Stars and Stripes flying on a celestial body millions of light years from Earth was a great moment.

[6] Although, as one of my friends pointed out, considering how the film ends humanity may ascend to the 5th

dimension shortly after Connor returns to our solar system.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I also find it interesting that in some of the more recent apocalyptic science fiction epics the heroes come from extraordinarily ordinary background. While, Cooper (McConaughey) in “Interstellar” was a NASA pilot and engineer his life as a farmer is far more visible within the story, the heroes in “Armageddon” were a crew of rag-tag oilmen, John Cusack in “2012” is a failing author and limo driver; Jeff Goldblum’s character who discovers how to defeat the invading alien species in “Independence Day” worked for a cable company, and perhaps to a lesser extent in “Deep Impact” the teenaged amateur astronomer Leo Biederman (Elijah Wood) originally discovered what became the asteroid—in the science fiction epic “Star Wars” who was Luke Skywalker before the introduction of C3PO and R2D2 in “A New Hope”? Yet, their heroics were only possible through international effort on various degrees of scale and magnitude. I would suggest that this also says lot about how Americans envision, imagine, and remember the past and project in onto the future as well. At any rate, really enjoyed your review!

I think you’re completely right. A review over at We’re History–which I’ll try to insert into my post (and forgot to originally do) makes precisely that point. The American Everyman needs a little help after all.

Thanks for the comment and the kind words!

I enjoyed your reflections on the movie. As a Star Trek fan, I always pay a lot of attention to how the US is portrayed in future-oriented sci-fi. That series strongly implies that nationalism is a relic of a bygone age, and that the nation formerly known as the United States no longer exists. The entire premise of The Hunger Games, by contrast, is based on the non-existence of the United States. But there this decline is supposed to represent a horrible declension rather than a welcomed utopia. And have you been watching Ascension? They reference history with kind of a “Mad Men in space” aesthetic and feature an American flag with a different configuration of stars! What is that about?

In the case of Interstellar, I admit that once they clearly established that there still is a United States, I stopped paying attention to those issues. So I appreciate the questions that you raised. They are good ones, though I’m not exactly sure what they say about the movie’s attitude toward American nationhood.

Finally, I don’t mean to quibble, but it wouldn’t be a comments section without a point-missing correction. As I recall, John Lithgow’s character was not the father of Matthew McConaughey’s character, but the father of his dead wife.

These are some great points. I’ve been meaning to watch “Ascension,” but the night it premiered I was still so perplexed by the ending of “Interstellar” I had to take a break from science fiction! But yeah, I was intrigued by the fact that the mission in the miniseries was an American one, being launched in the 1960s! I’ll have to check it out sometime. As for the USA in “Trek,” that’s an important point. There are numerous moments across the various series when Starfleet crew members encounter American emblems, and there’s not much of a sense of nostalgia for the characters, at least none that I can gather. America seems to be, at best, a memory from Earth’s past.

Then again, there’s also Ben Sisko in “Past Tense” talking about the Gabriel Bell riots–something I wrote about in one of the posts I linked to above. He mentioned those riots as being a crucial moment in Earth’s journey to being a peaceful world. Add to the fact that he didn’t want to enter a Holosuite program in Season 7 because it was set in 1962 Las Vegas–therefore he knew if it was realistic, it wouldn’t exactly be a welcoming place for him–and there’s a sense among a few character’s of America’s past. All intriguing facets to consider!

As for Lithgow’s character–I think you’re right. My apologies, guess I just plumb forgot that.

Really enjoyed this take, Robert.

To Mike’s point — the father/daughter pairings in the movie were super important. [spoilers ahead]

There were three pairings intertwined — Lithgow’s character and his absent daughter, Michael Caine/Anne Hathaway, Jessica Chastain/Matthew McConaughey. That first absence was like the blank space in one of those tile puzzles that let everyone else shift position, one character (well or poorly) filling the role left vacant by another, until in the end Murph takes Dr. Brand Sr’s. place, and becomes a mother to her father and a father to Brand’s daughter, who (we understand) will fill the place left absent by Murph’s mother. The father-daughter bond is the emotional gravity holding the whole thing together. It was a very touching film.

Thanks for the kind words! And the father-daughter relationships are the backbone of the movie. I considered briefly touching upon the role of women in the film in general–but as you can see, I’d written more than enough. But I’m glad you brought this up, because it’s a completely different film without those relationships.