In the 1970s, Jerry Falwell and other conservative evangelicals built their brand on cross-town busing.

I’m not talking about federally-mandated school busing to achieve desegregation – not yet, anyhow. For now, I’m just talking about the “bus ministry,” one of several evangelistic/outreach programs Falwell deployed in the late 1960s and early 1970s to turn Thomas Road Baptist Church into one of the fastest-growing congregations in the United States.

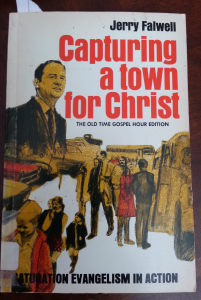

Falwell’s “bus ministry” features prominently in this cover illustration from a book he coauthored with Elmer Towns.

What is a bus ministry? Basically, it’s a program through which a church provides free bus transportation to its Sunday services for members and/or visitors. Falwell did not invent the idea of bringing in the sheaves via bus, and his was not the only church using bus routes to boost Sunday attendance and garner new converts.[1] But his very visible success surely helped make bus ministries one of the go-to tools championed by leaders of the church growth movement among evangelicals in the 1970s.

A key leader in the 1970s church growth movement was Elmer Towns, a member of Falwell’s church and a co-founder of Liberty University. In 1973, Towns co-authored a book with Falwell describing the ministries of Thomas Road as models that other churches could follow to see similar growth. “The Sunday-school bus ministry has the greatest potential for evangelism in today’s church,” Towns wrote in Capturing a Town for Christ (Fleming H. Revell Co., 1973). “More souls are won to Jesus Christ and identified with local churches through Sunday-school busing than any other medium of evangelism” (34). This is a broad statement about the evangelistic potential of bus ministries in general. Towns follows up this general endorsement of church bus programs with an explanation of what makes the bus ministry at Falwell’s church stand out:

Many bus workers only work in the housing projects, ghetto areas, and among the poor in the slums. All people within a community must be reached, the poor as well as the affluent. Thomas Road Baptist Church has sixteen buses that operate in middle-class neighborhoods of twenty-five-thousand-dollar homes and above. One bus brings in thirty-five riders from the status Boonsboro district, while the next bus that unloads on Sunday morning is from the Greenfield Housing Project, and the bare feet and dirty clothes indicate a poverty level.

Lynchburg has only fifty-four thousand people and some feel the Sunday-school bus ministry has reached its saturation point. Now twenty-one buses leave the city limits and bring children in from rural areas and distant towns such as Bedford, Alta Vista, Appomattox, Amherst, and Thaxton. One reaches fifty miles to Roanoke (35).

There’s a lot

going on in these two paragraphs, and a lot going on around them. Housing projects, ghettos, and slums – in 1973 (and today as well, I guess) these words could be used to introduce race into a discourse without ever naming the issue. So I think Towns isn’t just talking about “the poor as well as the affluent” here – he’s also talking about black urban poverty and contrasting it with white suburban affluence. The assertion that “all people within a community must be reached” is not offered here as an argument that more churches should use busing to bring the black urban poor into their midst, but rather as a justification for churches to consider providing free bus service to white affluent suburbanites who might wish to become members. Busing can bring people of “status” into the church. And busing over long distances – well, that’s not a problem. What’s wrong with busing new members into a church located fifty miles away from where they live, if that’s where they want to be on a Sunday morning?

Is it just me, or does anyone else see the irony of this apologia for long-distance busing coming from white Southern Baptists in 1973? Even if I were to read Towns’s description of the bus ministry as a celebration of the church’s ability to bring black and white and rich and poor together in fellowship, it would still seem like an odd argument for church leaders from the Religious Right to be making in 1973, in the midst of nationwide controversy over federally-mandated busing to desegregate schools.

More to the point, did anyone else see the irony of such pro-busing arguments at the time? Did people see these two issues – church busing and school busing – as in any way connected?

As it turns out, some people did see a connection. For example, a 1972 article

in the “Religion” section of the St. Petersburg [FL] Times

opens on this ironic note: “Cross busing, a hot political issue this year, has taken another turn on the Suncoast as many churches institute or expand their own programs of cross busing, busing children and elderly people to church and Sunday school for Jesus.” The opening lines of the article aren’t just a newswriter’s hook; they reflect the oppositional – or at least skeptical – stance of some people who had attended “bus outreach clinic” sponsored by the Pinellas Baptist Association. During a Q&A session about bus ministries, the newspaper reports, “[a] woman sitting near the back of the chapel asked pointedly, ‘Do you bring in colored?’ ‘We bring in black and white,’ the minister replied. ‘We don’t check them. The kids don’t check them by race though I’m sure some of the deacons do,’ [the Rev. John] Pelham added as laughter cleared the air of tension.” Apparently, the tension wasn’t cleared for long. The article continues: “A young man asked if [the minister’s] church had any trouble. The minister tossed the question back to the youth who blurted out, ‘Have you had any trouble with the colored – fighting or anything?’ Pelham shook his head, perhaps more at the question than the answer, ‘No.'”

A few years later, the local newspaper in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, ran an article discussing various bus ministries in the region. The article quotes one minister who pointed out the irony of some Christians’ contradictory position on busing issues: “Some of those who condemn busing in the public school system heartily endorse busing from areas outside their community which is an interesting conflict of viewpoint, to say the least.”

I think so too. I think this is a historically interesting conflict, or at least a historically interesting juxtaposition of two very different ideas about what buses are and aren’t good for.

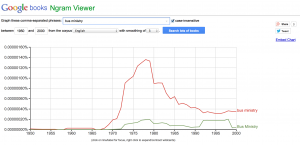

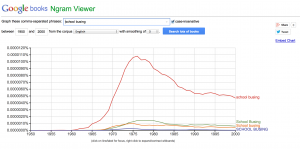

Out of curiosity, I ran a Google ngram to compare the frequency of usage of the terms “bus ministry” and “school busing”. Here’s what the results looked like (click images to enlarge):

These graphs show that usage of these two terms rose and fell almost in tandem. What they don’t show – indeed, what they can’t show – is what people using these terms might have meant by them at the time, or what the paralleled temporal trail of these terms might mean for understanding that time now.

I am interested in exploring this problem further. In the meantime, I’d like to hear what you all think.

__________________

[1] For example, according to a 1974 article from the Austin American Statesman, First Baptist Church of Dallas started a bus ministry in 1952, and a few large churches in Texas had been operating bus ministries before the 1970s. See Jack Keever, “Texas Churches Run ‘Ministry on Wheels,'” Jul. 11, 1974, Austin American Statesman, p. 64.

9 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

This is a fascinating piece, LD. Thanks so much for writing it, because I think what you have here is another intriguing perspective on the 1970s.

From what I can tell, this is an interesting moment in the history of evangelical Christianity in the late 20th century. As you know, the mid-70s was the era in which these groups were first beginning to flex their political muscle. However, this particular idea of “cross-busing” in terms of bringing people to the church is an interesting one to contrast with busing going on in regards to bringing people to schools.

My apologies for rambling a bit–I’m just trying to tease my own thoughts out here, because Sundays have been described as the most segregated day in America due to the racial composition of churches. So to see them pursuing a strategy to potentially bring in people across a racial and class divide is interesting. I know you point out that it’s just as important for them to be bringing in the well off as well as the poor (and black)–but the potential for interracial, as well as cross-class, interaction in these churches in the early 70s is something to think about.

I think, in some sense, it points back to Cowie’s argument in “Staying Alive”, where he argued that the politics of the 1970s weren’t quite liberal or conservative–they were simply an attempt by Americans to grasp at and face problems that seemed intractable. Here, I can’t help but think about the fact that all this is happening right as the Civil Rights Movement has ended, the War on Poverty is essentially dead, yet Falwell’s church is trying to save as many souls as possible. I’m intentionally putting all of that into one statement–my brain is thinking that all of that together might have produced an interesting intellectual (and spiritual) stew that, in the 1970s, meant cross-busing of one type was just fine, while the other (government-mandated) was virulently opposed by many people, black and white.

My apologies for rambling–but I wanted to start the conversation on this. You’re right, there IS a lot going on here. Do you have any idea when these programs ended, if they ended at all?

Robert, thanks so much for the comment.

We are on the same page, I think, in terms of thinking that untangling some of the knots of American cultural history will require following the ties that bind American evangelicals across the color line. (Untangling some of the knots of present cultural crises might well require the same perspective.) I tried to get at this in my “pastoral work” posts, and I think that’s where I’m headed next with this line of inquiry, so I probably should tag this post accordingly.

Last night I skimmed the first few chapters of William Martin’s smart, smooth book, With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America. He spends some time discussing the intersection of burgeoning evangelical influence and the struggles of the Civil Rights era — for example, he interweaves the reminiscences from Falwell et al with the recollections of Black evangelical leaders in Lynchburg. Wright mentions Falwell’s bus ministry in passing, framing it as an outreach effort aimed primarily at bringing African Americans into the church. That’s not the impression I got from reading through the 1973 book. Usually Martin pushes back against some of Falwell’s retrospective refashionings of his earlier positions on segregation — but it seems to me that “bus ministry as an effort to attract African-American members” might be a bit of revisionist memory that slipped past Martin’s radar screen.

Nevertheless, the evangelistic aims of people like Falwell were not just convenient “cover stories” for their “real” intentions. I think Falwell believed the gospel he preached. And — as Sokol pointed out in *There Goes My Everything* — the Civil Rights movement confronted many white evangelical Christians with a situation where some of their deepest beliefs were brought into conflict with each other. It seems that some tweaked their faith to accommodate their prejudices, but some tried to set aside their prejudices to accommodate their faith. These changes of heart might look like a case of political expediency, and they might very well be just that, viewed in a certain light. But they might also have been sincere efforts to live up to the ideals of Christian fellowship. (As David Hollinger reminded the assembled USIH faithful last fall, Galatians 3:20 is right there in holy writ — not to mention Rev. 7:9-10.)

Anyway, I think part of the uneasiness that comes through in some of these news articles from the time — I only quoted two, but there are plenty out there — is an awareness that offering a bus ride to whoever wants one might very well open a door across that color line. The uneasiness comes not just from people’s prejudices, but maybe also from the realization that once that door is open, they can’t in good faith close it. I don’t know though — I have to look at this more.

As far as bus ministries go, there are lots of mega churches that still operate bus programs, including several big ol’ Baptist churches in the Dallas area. I just did a quick local google, and found this one from a DFW-area church: Lavon Drive Bus Ministry. However, my sense is that church growth experts have shifted focus to taking church to people where they are, rather than vice versa. I hope to write about this some next time, but it occurs to me that this shift “back” to reaching out locally via small groups (as opposed to getting everyone to drive half way across the county to attend one of the half-dozen services running round the clock at the megachurch) is not coincidentally connected to gentrification and the “flight” of affluent and hip gen-Xers from the suburbs back to the cities. That’s my hypothesis anyhow.

Thanks for the response! Good idea mentioning Sokol–your post points to an intriguing intersection between Southern history, the 1970s, and the rise of the Religious Right.

Hopefully more folks will chime in. A great deal to think about here!

LD,

Thanks for this great find and for your (and Robert’s) excellent analysis of the complexities involved here.

I found myself wondering not just about race, though, but also able-bodiedness. Was part of this busing initiative an attempt to reach out to those who needed assistance–and not just transportation–to get to church on Sundays? If so, that might smooth out some of the irony of this strong advocacy of long-distance busing in the midst of the school-busing controversy.

Nice post, LD. Bus ministries were very popular in fundamentalist circles in the 1970s. From what I can tell, they were all imitators of a pastor in Hammond, Indiana named Jack Hyles, who started a bus ministry in the late-1950s. Even if you account for the inflated numbers–he counted pretty much everyone who “prayed the prayer” as part of his church–he had at least 20,000 people in attendance on most Sunday mornings. He also became notorious in fundamentalist circles in the 1980s for promoting “KJV-onlyism,” but his bus model was widely adopted. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Hyles

Andy, good question. Bus ministries were (and still are) a way to provide transportation to church for the elderly, for those who can’t drive, etc. — including younger children who obviously can’t drive themselves to church. So such programs were a “ministry” in the “pastoral care” sense — ministering to the physical needs/circumstances/limitations of people. The programs were “evangelistic” in the sense that the “bus captains” would go out into the neighborhoods on their route on Saturday mornings to knock on doors and invite people to ride the bus on Sunday — parents were welcome to come with the children — with the idea being that you would bring in people who weren’t attending any church or who had never “heard the gospel” or “made a decision for Christ” (terms which I am just going to leave sitting here for now!). The “pastoral” aspect of the bus ministry is discussed at a few places in the Towns/Falwell book, but the emphasis throughout the book is ministry as a means of evangelism. At any rate, the discourse within churches about what these programs were for would have been more complicated — the conversation would have been “about” many things besides race relations (and maybe not even about that explicitly). But I wanted to isolate that particular strand for further study.

Paul, thanks for the comment and the link. And yes, my understanding is that the 1970s were the heyday/highwater mark of bus ministries. This coincides not only with busing controversies, but also with the fuel crisis — maybe that made bus rides more attractive for people who wanted to attend church, but it would have made these programs more expensive to operate.

Also, I wanted to mention that Erik Loomis picked up this post over at Lawyers, Guns, and Money — you all might want to check out the discussion there. (And I saw that John Fea linked to the post as well — much appreciated!)

I have long perceived that, for evangelical Christians, there are lots of terrible evil things that become awesome when they are about the Bible or Jesus: sexy movies (DeMille), violent movies (Passion of the Christ), haunted houses (Hell House), rock music, and many more. Not really a double standard so much as a single standard. So busing may have been another example.

LD: Thanks for this article. A great find and an interesting juxtaposition. I am currently working on a book about local control of schools in the postwar era, and race-based busing obviously plays a pivotal role in the narrative. How religious communities conceived of localism is an interesting layer to add.

A couple of thoughts:

1) As several scholars have pointed out, despite its diehard commitment to “states rights,” the South actually had very little tradition of localism in education. To the contrary, Southern districts were often established on a county-wide basis with widespread busing as early as the 1920s, initially as a way to bolster segregated schools (counties ensured enough children to maintain separate systems, as well as enough money to do so.) The irony is that without legal segregation, county-wide districts made busing for desegregation much more effective in the South than elsewhere. Moreover, as Lassiter argues in “The Silent Majority,” many suburban communities approved of busing as a moderate/modern solution to the race problem. One is reminded of the silence greeting Ronald Reagan’s anti-busing line (“a failed experiment that nobody wants”) when he visited Charlotte. So it is not SO remarkable that Southerners would favor busing for the Lord.

2) In addition to the impulse to save as many souls as possible, I wonder whether this does not reflect some ambivalence on the part of Southern Baptists about their changing congregations and the effects of what Bill Bishop described as “The Big Sort.” For a denomination with working-class, down-home roots the rise of the New South, suburbanization, and country-club conservatism may have represented something of an identity crisis, requiring a reach across geographical and demographic divides for their own authenticity and self-conception.

Anyway, thanks again for the post!

–Cam.

Cam, thanks for this added insight about the history of busing and schools in the south. It makes sense, and in some ways adds to the irony of the national situation in the 1970s. The wonder may not be that Southern Baptists favored busing for church. The bigger surprise might be that, with the increasing involvement of some SB leaders in national political debates/concerns, they found themselves arguing “the other side” of the busing issue. Adds to the irony, reverses the polarity.

On point #2 — If I understand you correctly, you’re saying that maybe as Southern Baptists’ mainstream clout grew, they grew nostalgic for the sense of community and the sense of purpose that came from being part of an “outsider” or low-status group, and busing people in across the class line, if not across the color line, was a way of reconnecting with their history — or, perhaps, nostalgic “memory” — of humble origins. I see the logic of that hypothesis, but I don’t know that I’d look for evidence in these 1970s “church growth” strategies. At my blog I posted a few graphs of a Washington Post article on Falwell that talks about his ambitions to build a “Christian empire” (his words) and raises the question of whether/how his congregation would vote — the article conveying the sense that Falwell’s church, at any rate, was all about increasing in power/influence. In the “Capturing a Town for Christ” book (what a martial and acquisitive title!) there’s a marked conflation of quantity and quality — that God’s favor/blessing is evident in growing numbers, that numbers (attendance, giving, baptisms, etc.) are in fact a reliable metric for gauging the spiritual vitality of a church. More than anything, that fixation on numbers — and does that ever have a long history in Southern Baptist life! — may be the lingering legacy of the “wilderness years” of being on the periphery of power rather than at the center, especially in a democratic society. The more Southern Baptists there are, the logic would go, the more they “should” have proportionate influence in matters cultural and political, and their (perceived) lack of influence/clout despite their numerical increase would be a proof of “persecution.” That is a win-win for Falwell et al — viewing growth as a sign of God’s favor and a proof of the efficacy of preaching the gospel, but also viewing growth as evidence of marginalization as the direction/drift of the culture defies the will of the “moral majority.”