Few bands can lay claim to visuals as striking as Black Flag’s, and that imagery is central to Black Flag’s anti-systemic working-class conservatism. Greg’s brother Raymond Ginn (nicknamed Pettibon by their father) not only came up with the name, but also produced the iconic, vicious pen and ink artwork that first adorned countless photocopied flyers for shows, Black Flag and other SST bands’ record sleeves, and soon thereafter bound volumes and gallery walls. Pettibon’s art, together with Black Flag’s producerism and Carducci’s writings on rock, coalesced to forge a new working-class counter-culture in the long shadow of the counter-cultures of the 1960s.

Reverberations of the New Left in the ‘80s Underground

The legacy of the “sixties” as a cultural and political phenomenon looms large in Pettibon, Carducci, and Black Flag’s work. Pettibon drew stark and, typically single panel illustrations modeled on political cartoons and made homemade movies that frequently featured such infamous ‘60s figures as Charles Manson and his Family, the kidnapped Patty Hearst’s SLA alter ego Tania, and the Weather Underground.

Pettibon savagely deploys these subjects to mount a scathing critique of what he saw as the era’s prevailing privileged, white counter-cultural elitism. Each of these figures underpinned Pettibon’s belief that the ‘60s did not represent a lost dream of radical change, but a moment in time best remembered by the blinding delusions and overwhelming narcissism of people who never stood a chance of changing the world in the first place.

Like his highly influential drawings, Pettibon’s forays into filmmaking in the late ‘80s explore in great detail a cynical and conservative vision of the ‘60s as decadent, ludicrous, and above all exceptional moment in American history. Shot on camcorders and peopled with various SST artists and hangers-on, these purposefully amateurish, homemade movies illustrate an era out of step with an almost Hartzian notion of consensus. Pettibon’s suggests that the broadly collectivist ethos of ‘60s antiauthoritarianism stood awkwardly apart from a stoic individualism at the core of American political culture.

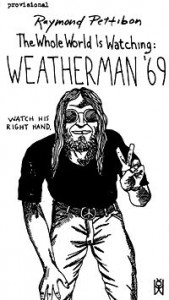

To explore these themes, Pettibon seized on the sectarian implosion of the Students for a Democratic Society for his first full-length movie, 1989’s Weatherman ’69: The Whole World is Watching.

A pitch-black, Americanized parody of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise, Pettibon imagines the urban guerillas of the Weather Underground—including Bernadine Dorhn, Jeff Jones, and Mark Rudd—hunkering in a grubby, claustrophobic apartment somewhere in LA. Like Godard’s groovy, Maoist character study of radical French university students, Pettibon’s rambling vignettes follow the ideological rants, denunciations, self-criticism sessions, paranoia, and interpersonal psychodramas of a self-described revolutionary vanguard on the run from fascist pigs.

This vanguard leadership, as Pettibon eagerly reminds the viewer time and again, is made up of petulant kids, “Yale econ majors” and “social engineering” students from Columbia, the children of professors of “Marxist mathematics” at Harvard. Dedicated “To stop being honkies, and [becoming] stoned revolutionaries,” the group spends its days convinced Amerika will fall any minute as they sit cloistered away from the tyranny of the capitalist “motherland.”

Demanding to know “what you’ve done for the revolution?” the gathered tally their work serving the people. One cadre declares, “I’ve read a lot of Marx, I got paper cuts from the Little Red book.” Jeff Jones (played by Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth) proudly reports to killing four janitors bombing ROTC buildings. Another rank-and-file Weatherman, played by Mike Watt of the Minutemen, upholds the cell’s one communal toothbrush. When offering the visiting Allen Ginsburg a tab of acid, the Weathermen claim LSD manufacturing is the group’s primary source of income—aside from what they still get from their fathers.

Dorhn, portrayed by Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth, is depicted as the group’s de facto leader. Dorhn is bent on enforcing strict sexual discipline, denouncing monogamy as bourgeois individualism and premature ejaculation “as a symptom of late capitalist, racist white man’s rule.” Otherwise, Dorhn’s most bitter struggle is with Jane Fonda over who will be the Movement’s leading celebrity.

Likewise, Pettibon frames the urban revolutionaries’ direct link to the struggle for racial equality and Black Power as nothing more than a facile outgrowth of their own consumer habits. While smoking a joint they sort through the cell’s record collection. Louis Armstrong is deemed an “uncle Tom.” The Supremes are dubbed “an embarrassment,” and, as one Weatherman claims with dubious authority, “Bobby and Stokely want us to waste it.” A snarling Jeff Jones decries James Brown as a “Nixon supporter,” while admiring Muddy Waters and Isaac Hayes as “far out.” Meanwhile another very stoned cadre looks aghast at white Detroit blues-rock group Frijid Pink and gasps, “Is this politically correct?”

In the end it’s all revealed that the Weather Underground are merely cultivating their connections with the children of media moguls to see that their self-styled revolution will in factbe televised on CBS. Dohrn celebrates by snorting lines of cocaine cut into the shape of a swastika. And fin.

Two decades on from the Days of Rage and the ’68 Democratic convention, Pettibon looked back and saw only a clutch of deluded and self-absorbed adolescents isolated in Ann Arbor and Cambridge and thoroughly disconnected from the mainstream of American society—especially working people themselves. In Weatherman ’69,the Weather Underground’s politics, and with it much of the era’s utopian ideals, are discarded in fell swoop as the inane byproduct of bored and affluent white kids.

Pettibon underscores what he sees as the spoiled childishness of the revolutionary left by literally opening the movie with a young child lecturing the camera about the meaning of communism:

“I don’t want to grow up in a world without communism. If I’m a communist, I don’t have to work or anything, I can play all the time. I can set bombs off all the time and blow up churches. …I don’t think it’s that serious, I just do what I want.”

This clichéd and conservative caricature of communism meshed with the celebrations of self-sufficiency, manly hard work, and individualism that underpinned Black Flag’s producerism and Carducci’s rockist attack on liberal elitism. Pettibon, Carducci, and Black Flag imagined themselves creating a real working-class counter-culture that by definition would be a rejection of the inherently foreign collectivism fetishized by affluent, collegiate white youth.

The Weather Underground, Pettibon asserts in his savage satire, never had a clue what working people wanted, and never could hope to connect with them politically, culturally, or aesthetically. But working people are assumed to be white men. Though Pettibon takes great delight in lampooning the Weathermen as they curse their white skin and wallow in white guilt, the civil rights movement and Black Power are themselves also presented as something just as alien as the white New Left. Thus, the big joke of Weatherman ’69 is an answer to that perennial question of “why no socialism in America?” The farcical case of the Weather Underground ultimately illustrates that a basically white, conservative, anti-collectivist ethos drives American political culture.

Weatherman ’69 does often works as a very funny black comedy puncturing the truly laughable pretensions of student revolutionaries. But Pettibon mobilizes his vast working knowledge of left politics to make Weathermen ’69 a sweeping and savage generational statement, sharply separating the working-class children of the ‘60s from the always already doomed dreams of their parents’ social betters. It’s at once a bitter condemnation of elitism and privilege, and, in Pettibon’s hands, a deeply flawed argument for the inherent conservatism of American society.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Kit–once again, a great post!

I was watching a great documentary on John Waters’s muse Divine today, and one of the interesting details of that film was that one of their earliest collaborations was a comic reenactment of the Zapruder footage (with Divine as Jackie O). Apparently, no one found it as funny as they did (I thought it was pretty funny).

That got me wondering about historical re-enactment as a certain modality of the grotesque. Since the double is always uncanny, it makes sense that trauma-LARPing would be a favored practice within the repertoire of aesthetic transgression. It strikes me that this sort of procedure has something to do with the sense of history-as-delirium that many people who grew up as kids during the 1960s speak about (I am sure that a version of this also true of those born in the late 1990s, for whom the Bush Era was an ambient childhood background)… It sees true that this sense of delirium is very important in the aesthetic of Sonic Youth (with which, admittedly, I am much more familiar than Black Flag), whose members, you point out, are featured in these films. This is true, too, of the art of Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy, and the novels of Denis Cooper, all of which overlapped with the personnel and times and places you discuss above… I wonder how this broader context helps us make sense of the class politics of Black Flag?

Or, perhaps, to put it another way, if there is a meaningful distinction to be drawn between the working class art of the 1930s (which sought to penetrate beyond the delirium of capitalist history to the truth of class struggle) and that of the early 1980s (which sought to reproduce that delirium as against the artificial narratives of, I don’t know, Peggy Noonan and Milton Friedman?)

This is a great post, and I’d like to echo Kurt’s sentiments above. This seems to be part of a larger conservative project to shape how Americans remember the 60s–one that was aided by the retreat of the Democratic Party in the 1980s on a variety of issues (a retreat that, many moderate and liberal Dems would argue was necessary to remain a viable choice in the 1990s). My statement isn’t to suggest some sort of conspiracy. But my own work on the 1980s, and how partisans in that era remembered the 1960s, backs up what’s being talked about here.

Heck, the section in this Jacobin piece on liberalism in the United States that addresses the ways in which liberals remember Mandela and MLK speaks to your argument too: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/07/why-im-not-a-liberal/

Thanks so much, Robert and Kurt. I really appreciate your comments, and they greatly helped clarify my thinking.

To Kurt’s question I think the comparison with the Cultural Front is a very useful point of comparison. And Robert’s point that ’80s conservatism required rewriting “the sixties” is right on. I hadn’t thought of the quality of delirium that you mention, but on second thought that’s precisely what distinguishes the film as an expression of working-class conservatism. Whereas the Reaganite bourgeois/ruling class conservatism of the ’80s insisted that “the sixties” changed too much in American society, the surreal and bizarre nature of Weatherman ’69 is meant to underscore the point that nothing about the era ever threatened to radically upend anything. Pettibon et al.’s working-class conservatism rests on a weary cynicism that any change would probably be at the expense of working people because it’s elites (including their dissident kids) who make history.

Also, for those who are interested, Weatherman ’69 is available on youtube (apparently with Pettibon’s permission):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JI_Y_1NCwCw

Hi Kit,

I’m a freshly minted English Ph.D. with an article forthcoming on Black Flag in the journal “Criticism,” and have read your posts with great interest. I think this idea of “anti-systemic working class conservatism” is an interesting one. Is it your own coinage or were you influenced by other scholars? I agree that BF and their handlers don’t fit into a typical paradigm of classical liberalism, but what would you say about classifying them merely as anarchists or maybe anti-systemic working class radicals? One concern I had about your posts is that they didn’t seem to account for the diversity of political opinions or ideologies in the band. For instance, I think that Chuck Dukowski, who wrote many of their original songs, has a much different perspective on these things than, say, Rollins or Ginn, let alone their producer SPOT, Kira Roessler, Keith Morris, Ron Reyes, or Bill Stevenson (the list goes on…), all of whom were important contributors to the band’s sound. And speaking of sound, would you really consider THAT conservative? And isn’t sound the primary sense modality through which the band was consumed? I think that it’s important to consider the band’s visual style and presentation, but I worry that you’re giving too much weight to the ideological opinions of those who surrounded the band, Carducci and Pettibon in particular, and not the band themselves. After all, Pettibon has virtually severed his ties with the group and Carducci has always been something of a fringe figure, no matter how brilliant his writing is. (For what it’s worth, he claims in the introduction to “Enter Naomi” that BF embodied Randian libertarian ideas. Although I don’t exactly agree with that point of view either, I understand what he’s saying.)

As a scholar who focuses most of all on the radical and transgressive aspects of the BF/SST project, I found your posts to be a necessary reminder of the ways in which they did not always live up to these ideals, but I still worry that your classification of the band as a whole as conservative lacks subtlety. For instance, you mention that the Ginn family were “Eisenhower anti-communists,” but how many other “Eisenhower anti-communists” do you think were listening to BF in the eighties? Similarly, I agree that there is a radical hostility towards the New Left in “Weathermen ’69,” but I’m not sure if that’s really conservative. To me, it seems just as likely that Pettibon and his co-stars Kim Gordon and Mike Watt, for instance, were attempting to outflank the Weather Underground. Whether that strategy is successful or not is another question, but it’s certainly not conservative in the same way as, say, Reagan or Bruce Springsteen, who I think the film criticizes indirectly through its ironic reappropriation of the 1960s.

I’d love to continue this conversation on or offline, and though I may seem critical, I loved the posts.

–S

Thanks for the thoughtful comments and critiques, Shaun. I really appreciate it. You pose a number of important questions, so I’ll start with a few preliminary responses. It would be great to continue the discussion here as well as offline.

By using anti-systemic working-class conservatism (a term coined by none other than Kurt Newman) I intended to frame Flag’s aesthetic primarily as a reaction against the cultural and ideological systems of postwar US society–primarily the homogenized corporate mass media and brutal, technocratic Robert Mcnamara-style liberalism of the 1960s. Again, the legacies of the 1960s are crucial in framing the band’s political imagination. Thus Black Flag’s condemnation of racism, police brutality, stifling suburban conformity, etc. are directed backwards to the failures and atrocities of Great Society/Vietnam/Chicago ’68 liberalism rather than forward to the unfolding Reaganite-bourgeois counteroffensive. While drawing on anarchist and libertarian ideas and attitudes, Dukowski’s famous quip “anarchy for me, tyranny for you” is similarly backward looking and a basically conservative response to the decay of relative postwar working-class affluence (and at same time not an embrace of New Right California conservatism).

You’re absolutely right that Dukowski deserves more attention because he really was the band’s spokesperson and theoretician in its heyday. Though as you say somewhat peripheral, I do think Pettibon and Carducci capture the sentiments swirling around the band in the 1980s. In turn they made something ideologically coherent, but perhaps not wholly representative, out of the disparate influences brought to the band.

As for Watt and Gordon in Weatherman ’69, I think you’re on to something about their own interventions in that film that break with Pettibon’s own agenda (certainly Watt and D. Boon made up the Popular Front left bloc in the SST world).

Sonically, my take is that Black Flag’s aggressively far out reimaginings of punk via metal and jazz remained similarly invested in recreating a more adventurous interpretation of ’70s hard rock. Reading the recollections of different members, especially those of Keith Morris, in Steve Chick’s Spray Paint the Walls highlights how the band hoped to use punk as a short cut to recreating the stadium jams they all really dug.

Much of my thinking about Black Flag has been focused on their later years (which I admit is my favorite). I find myself drawing on the interviews and candid moments captured in Markey’s Reality 86’d to get a sense of the band’s sensibilities, but that’s not the most representative moment in the band’s history.

You’ve given me much to mull over, and these preliminary responses will keep me thinking about all of this. Let’s keep the conservation going. I’d love to read your forthcoming article on Black Flag, too!