The first few title cards of D.W Griffith’s 1914 film Home Sweet Home set forth the work’s subject matter and aim.[1] The film’s story, we are told, is “suggested by the life of John Howard Payne and his immortal song, ‘Home, Sweet Home.'” Here a songwriter and his song get equal billing as the inspiration for the unfolding drama. In mentioning the songwriter first, the text presumes some audience familiarity with the name and perhaps the life of John Howard Payne.

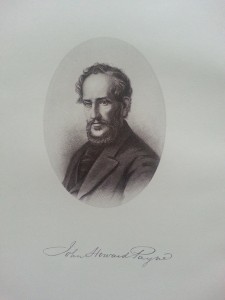

A child actor on the American stage in the early years of the nineteenth century, Payne was considered a prodigy by his contemporaries. He achieved wide acclaim throughout the Republic for his precocious performances as Norval and Hamlet – he was, in fact, the first native-born American to play Hamlet on the New York Stage.[2] In 1813, at the age of 20, Payne sailed unaccompanied to England, where he was, in his own words, “given celebrity.”[3] After a few years, with fewer and fewer leading roles coming his way, Payne turned to writing for the stage as a way to earn money. In 1823, his musical melodrama, Clari, the Maid of Milan, opened on the London stage, and he gained near-immediate fame in the English-speaking world as the author of the song “Home, Sweet Home,” an instant hit on both sides of the Atlantic. Though Payne wrote many successful stage plays during the two decades he lived abroad in Europe (including Brutus, later a vehicle for Booth family fame), and though he was subsequently appointed twice as the United States’ consul to Tunis, where he died and was buried, Payne was chiefly known and later remembered as the author of “Home, Sweet Home.” The song made its writer matter.

Griffith’s introduction to his film implies as much: he gave writer and song equal billing, but only the song is “immortal.” Furthermore, in framing the life of the songwriter, the film’s intro cautions that the ensuing narrative will not be “biographical” but instead a “photo-dramatic and allegorical” presentation which “might apply to the lives and works of many men of genius, whose failings in private life have been outweighed by their great gifts to humanity.” Thus, besides promising a visual treat, the film pledged to present some version of Payne’s life as a sort of parable or moralizing tale along the theme of the morally flawed artist who is in some sense redeemed by the goodness of his work. And the film proceeds to do exactly that – and more.

The allegory of the film unfolds in five brief episodes, the first and longest of which portrays a simplified biography of John Howard Payne. In Griffith’s version of Payne’s story, the artist leaves mother, home and sweetheart (played by Lillian Gish) to seek his fortune in the world as an actor, a profession which drags him into a dissolute life. His mother and sweetheart find him in dissipation, and he promises to amend his ways. However, he reneges on his promise, and the next sequence shows him “in a foreign land” – England is implied — where he meets with professional and financial success. But in that place far from home he is seduced by “the worldly woman,” and ends up in debtor’s prison. Meanwhile, his sweetheart at home continues to wait and pray for him. Upon his release from prison, he finds himself deserted by all his former companions. Friendless and penniless, his thoughts turn homeward. He takes up pen and paper, and “adversity spurs the writing of the song.” At this point in the film, the lyrics of the entire song are displayed in a series of cards on the screen so that the audience can sing along with the piano. The sequence ends on the repeated refrain:

Home! Home! Sweet, sweet home! There’s no place like home!

This sequence is followed by a scene showing Payne’s mother receiving “evil news of her boy.” The evil news concerns Payne’s imminent death. No longer merely in a foreign land, Payne is now in “an alien land.” We see him on his deathbed, indifferently attended by two men in vaguely Arab garb. As the two men fan him on his bed of fever, Payne clutches his song to his chest, breathes deeply, and dies. Another caption card adds pathos to pathos: “The true and the false alike went into equal silence.” Following those words, we see Lillian Gish’s character laid out for burial, surrounded by lilies – hardly a happy ending.

This bleak biographical sketch is followed by three short and unrelated episodes depicting everyday people who were saved from committing horrible moral failures by chancing to hear, in their moment of crisis, the music of “Home, Sweet Home.” A fortune-seeking miner who almost betrays his promise of betrothal, a mother who is on the verge of taking her life when she finds both of her sons dead after a bitter duel, a young wife who has foolishly agreed to keep a tryst with a lecherous suitor while her good and loving husband sleeps – all these are saved from moral ruin by the intervention of Payne’s song. The miner in the boom town hears an accordion player singing “the old familiar song” and abandons his search for fortune to return to the woman he has promised to marry. The “grief-crazed mother” hears a wandering peddler singing “Home, Sweet Home” and drops her knife from her hand, so that thanks to the song she becomes “the remnant saved.” And in “the wife’s moment of weakness,” when she is headed out the door to meet her suitor at last, she hears the neighbor across the hall playing “Home, Sweet Home” on his violin. She remembers the song from her wedding day, and instead of going to meet her lover she goes and wakes up her husband. Apparently she found in him the answer to her desires, for the next scene shows them ten years later, surrounded by a brood of happy children. In each of these cases, “Home, Sweet Home” serves a salvific function, redeeming sinners from the error of their ways and setting them securely on the path of righteousness.

In a visually and thematically astonishing and imaginative “Epilogue,” Griffith extends the redemptive reach of “Home, Sweet Home” to its doomed author. The epilogue opens with a question: “And so, for countless services like these, shall not his faults be forgiven?” We then see John Howard Payne in hell. He is one of a crowd of nameless, numberless souls, all wearing robes, all bowed down, trying to claw their way out of a sulfurous pit but slipping back down the steep, smoldering walls of mercilessly dry earth. We see a close-up of Payne’s face as he desperately tries to “rise from the pit of evil.” It looks hopeless. But then a title card recalls to us the earlier promise of Gish’s faithful love: “I will await thee, dear my boy.” Next, we see Gish as an angel hovering over the landscape – film layering techniques render her semi-transparent, and costuming and lighting make her luminous. When Payne sees her, he is able to stand up and stagger out of the pit. Then Gish is joined by a host of diaphanous angels. She reaches down, and Payne climbs up to her in the sky. He is now as ethereal and transparent as the “angel” whose love has redeemed him. She embraces him, and together they fly upward and fade into the clouds. “The End,” says the final title card, as the piano accompaniment swells to a crescendo on the chorus of “Home, Sweet Home.”

This is a remarkable early feature film, and it merits further study alongside Griffith’s later and more famous works – shades of the nativism which emerges more clearly in The Birth of a Nation, and traces of the aesthetic ethos defended in Intolerance, are both present here.[4] But as useful as this film might be in providing additional insights into Griffith’s future endeavors, it offers a great deal of insight into how Griffith’s audience had appropriated the past. For the narrative of Home, Sweet Home presumes certain shared cultural referents among the film’s intended viewers. For one thing, Griffith seems to have expected his audience to accept the song’s ubiquity and popularity as a crucial premise underlying the story. Indeed, the story’s dramatic impact depends upon the audience’s willingness to believe that the song “Home, Sweet Home” was so well known and so often sung that people from all walks of life might be expected to hear it.

More subtly, but no less significantly, the film is premised upon the audience’s acceptance of a particular moral judgment of the “life story” of John Howard Payne. Griffith was not de-mythologizing a highly esteemed cultural icon, nor did he expect his audiences to balk at his depiction of the songwriter’s character. Rather, as I will demonstrate in subsequent posts, he was drawing upon a widely-held view of Payne’s life as less than exemplary, so that audiences would be moved by the spectacle of this flawed artist redeemed by his flawless work. As a cultural artifact, then, this film captures even as it attempts to shape what “John Howard Payne and his immortal song” had come to signify for Americans in the early 20th century: the importance of (staying) home.

The process by which this early 19th-century writer and his best-known work became identified with a sentimentalized vision of the family home as the center of virtue, and of America as the homeland of the virtuous, was well under way decades before Griffith got hold of Payne’s story and song. But the process of cultural enshrinement was not quite the same for the song and the songwriter. As we will see in subsequent posts, “Home, Sweet Home” entered the cultural lexicon almost immediately after its 1823 debut, and was instantly imbued with a meaning upon which there was wide cultural consensus. The biography of John Howard Payne, however, was less amenable to a straight and simple appropriation by 19th-century audiences. Indeed, the “meaning” of Payne’s life story was contested while he was still living it. Moreover, some of the same plot points which Griffith and his audience viewed as in need of redemption – Payne’s sojourn overseas to pursue his acting career, and his death “in an alien land” – also posed a challenge to 19th-century writers who sought to draw a didactic link between the artist and his song. However, their approach to the problematic aspects of Payne’s life was quite different from Griffith’s later interpretation. And standing squarely between earlier moralizations about Payne’s life and death and the Griffith film is the dramatic intervention of William Wilson Corcoran, who bankrolled and choreographed Payne’s exhumation from Tunis and reburial in a Washington, D.C. cemetery.

To be continued…

[CUE DRAMATIC MUSIC]

[1] D.W. Griffith, Home, Sweet Home, 1914, available on DVD as Rare Films of D.W. Griffith, Vol. 2. (Pleasanton, Calif.: Classic Video Streams, 2009). This is, of course, a silent film–all quotations are taken from the title cards/caption cards containing the film’s narration/dialog.

[2] I will discuss Payne’s stage career in more detail in an upcoming post. On Payne as Hamlet, see Grace Overmeyer, America’s First Hamlet (New York, N.Y.: NYU Press, 1957; Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1975).

[3] [John Howard Payne], Memoirs of John Howard Payne, the American Roscius; with Criticisms on his Acting in the various theatres of America, England and Ireland. Compiled from Authentic Documents (London: John Miller, 1815), 5. Google Books.

[4]For an excellent overview of the production history of Home, Sweet Home, including information about budget and locations, as well as a somewhat different take on the liberties Griffith took with details of Payne’s biography, see Ben Brewster, “Home, Sweet Home,” in The Griffith Project, Vol. 8, Films Produced in 1914-15, ed. by Paolo Cherchi Usai (London: British Film Institute, 2004), 28-39.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Movie stuff at USIH = I approve!

Q: President of the United States when Lillian Gish started making movies?

A: William Howard Taft.

Q. President of the United States when Lillian Gish died?

A: William Jefferson Clinton.

That’s some life.

Well, it was either this or a meditation on “Blue Is the Warmest Color” and the problems of historical narrative. Not joking. As you can see, I went with safe and boring. Stay tuned next week for a disquisition on doilies.