I.

Two weeks ago I promised a brief series of 3-4 posts on what it means to have “a great books sensibility.” The first post outlined some theoretical considerations. I noted that my thinking about “sensibilities” is informed by the recent work of Daniel Wickberg, who in turn was inspired by the work of other historians and the writings of William James. I also laid out some characteristics of those with a GBS: a style of critical thinking, perhaps but not strictly linked to Adler’s How to Read a Book

; awareness of deeper ideas: components of reason and affect; the citation of prominent “names” and authorities in writing and conversation; positive and negative imitative behaviors; and the demarcation of legitimate thought using great books authors and works.

Given those preliminary considerations, I now turn to cases and examples. My hope is that these will both enrich and challenge my theory, or my hypothesis, about a GBS. I want these examples to show that this sensibility could have a ‘bottom up’ formulation—even while it was also proposed and promoted by intellectual elites. Again, my prior work on mid-century great books liberals focused on those elites and the top-down movement they helped create.

What follows is a revised extraction from a section on 1970s Chicago that I had to excise from the book. It’s drawn from the same section wherein I had written on Shimer College, posted here some weeks back.

II.

Chicago’s continued affinity for the great books idea found expression in many registers—in concerns over the fate of great books-based Shimer College, as well as in cuts to school great books programs and in reading group participation in the 1970s. It also arose in the case of a lifelong Chicagoan, Mary Lou Wolff. Rather than the top-down, universalist common-sense realism of Adler, the “local knowledge” of Wolff and these other enthusiasts constituted a regional sensibility, or even a regionally-colored common-sense great books liberalism. It can be seen as culturally “organized body of considered thought,” historically conditioned and defined, in the spirit of Clifford Geertz’s anthropological theorizing.[1] The story of Mary Lou Wolff demonstrates both how great books reading groups maintained legitimacy in Chicago in this era, as well as how those groups could inspire individuals into thoughtful political activism.

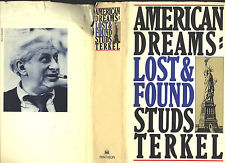

Who was Mary Lou Wolff?  She first gained notoriety in the late Sixties and early Seventies as president of the Saul Alinsky-inspired Citizens Action Program (CAP).[2] In telling her story to Studs Terkel, published in American Dreams: Lost and Found (1980), she recounted how she grew up the granddaughter of Italian immigrants in Chicago’s West Humboldt Park neighborhood, on Chicago’s West Side. She attended St. Mary’s High School, an all-girl school which existed from 1899 to 1976. It had a great books program, but it’s unclear whether, or in what form, that program existed while Wolff attended. After graduation she worked on a magazine at the Chicago headquarters of the Young Christian Workers.[3]

She first gained notoriety in the late Sixties and early Seventies as president of the Saul Alinsky-inspired Citizens Action Program (CAP).[2] In telling her story to Studs Terkel, published in American Dreams: Lost and Found (1980), she recounted how she grew up the granddaughter of Italian immigrants in Chicago’s West Humboldt Park neighborhood, on Chicago’s West Side. She attended St. Mary’s High School, an all-girl school which existed from 1899 to 1976. It had a great books program, but it’s unclear whether, or in what form, that program existed while Wolff attended. After graduation she worked on a magazine at the Chicago headquarters of the Young Christian Workers.[3]

Wolff eventually married.  After that she concentrated on her family, having nine(!) children and settling in Chicago’s North Side Mayfair neighborhood. In the words of a condescending, trying-to-be-clever female news reporter, the “outstanding achievements” of Wolff (a “fiery readhead” aged 45 in 1972), had been “fruit pies, children, and [a] clean home.”[4] But Wolff, a Roman Catholic, experienced an awakening after Vatican II in the mid-1960s. That awakening extended beyond religion and into politics when she created the Mayfair Civic Association (which was the occasion for the reporter’s visit and story). That group’s purpose was to resist the Daley Democrats’ “massive machine,” as it operated in her neighborhood.

After that she concentrated on her family, having nine(!) children and settling in Chicago’s North Side Mayfair neighborhood. In the words of a condescending, trying-to-be-clever female news reporter, the “outstanding achievements” of Wolff (a “fiery readhead” aged 45 in 1972), had been “fruit pies, children, and [a] clean home.”[4] But Wolff, a Roman Catholic, experienced an awakening after Vatican II in the mid-1960s. That awakening extended beyond religion and into politics when she created the Mayfair Civic Association (which was the occasion for the reporter’s visit and story). That group’s purpose was to resist the Daley Democrats’ “massive machine,” as it operated in her neighborhood.

Some members in that group, however, also expressed a desire for intellectual enrichment. They wanted a Great Books reading group. Wolff narrated to Terkel how it happened:

Another little bunch of women said: ‘Why don’t we have a Great Books discussion class?’ We all laughed. No people in this neighborhood would be interested. This is not that kind of a neighborhood. Within a few weeks, we had a Great Books discussion class made up of just the regular working-class people. One of the first [documents] we read is the Declaration of Independence. We spent three hours discussing the first half of the first sentence. This is the first time I, as an adult, ever discussed with other adults what the Declaration of Independence could possibly mean to me. There were intelligent people thinking about the same kind of things we were thinking about.[5]

The great books reading group helped Wolff transform her local Mayfair doings into something larger—i.e. joining Alinsky’s CAP group, which led Wolff into eventually co-chairing CAP’s Anti-Crosstown Expressway Association in 1972. The Crosstown Expressway was long championed by Mayor Richard J. Daley and would have existed as a north-south route along the Cicero Avenue corridor.[6] Wolff does not mention to Terkel whether her awareness of the great books idea was linked to her studies at St. Mary’s high school.

What did Wolff’s Great Books discussion group do for her and her fellow readers? In the context of her civic activism, as inspired by Alinsky and Vatican II, it seems that the great books idea gave Wolff what Sara Evans and Harry Boyte described as a “free space” to think. To Evans and Boyte “free spaces,” made concrete for Wolff in Great Books Foundation discussion groups, “are public spaces in the community” where “people are able to learn a new self-respect, a deeper and more assertive group identity, public skills, and values of cooperation and civic virtue.” They add: “Put simply, free spaces are settings between private lives and large-scale institutions where ordinary citizens can act with dignity, independence, and vision.”[7]

Wolff participated, then, in her own iteration of Adler’s midcentury great books liberalism (broadly defined), via the Foundation’s reading groups. She used the great books idea to craft a vision of a participatory democratic culture. For Wolff, great books also filled free mental space wherein she gained a greater understanding of liberties and responsibilities—her duties as a citizen. The great books idea enabled Wolff, returning to the evocative words of Tribune reporter Cornelia Honchar, to “jump from the frying pan to the fire of political action without batting an eyelash.”[8] Even while enthusiasm for the great books idea across America slipped in the 1970s, Wolff’s activities are exemplary of Mortimer J. Adler’s hopes and dreams for a critically-thoughtful American citizenry, as expressed in his earlier works Time of Our Lives, The Common Sense of Politics, and How to Read a Book. And it is no accident that Mary Wolff existed, as something of an exemplar, in Chicago. For Chicago had been the epicenter of the Great Books Movement since the 1930s.

Is Wolff merely a singular, if powerful, example of the outcomes of a great books-informed movement for civic engagement? Is it unfair to extrapolate from her? Perhaps.

Wolff distanced herself from Adler’s great books liberalism. She positioned herself to Terkel, rather, as an “awakened” citizen: “I’m a part of the awakening silent majority of black and white middle-class Americans who are tired of paying taxes, voting, [and] writing polite letters in hopes of getting change. …I’m not a college graduate, or a Woman’s Libber. I’m not radical or even liberal. I just want a break for the common people.”[9] Like many whose political yearnings and commitments were awakened in the crucible of the Sixties, Wolff sought a civic space, or sphere, outside of conventional left-right, Democratic-Republican politics. But she also wanted that space to be independent of cultural movements with a political valence. Although Wolff deliberately and consciously distanced herself from liberalism, her evocation of ‘the common people’ echoed Adler’s call for a common-sense philosophy based on universally accessible common experience. Wolff’s activism and great books-based thought existed in, and for, the shared public sphere.

Wolff distanced herself from Adler’s great books liberalism. She positioned herself to Terkel, rather, as an “awakened” citizen: “I’m a part of the awakening silent majority of black and white middle-class Americans who are tired of paying taxes, voting, [and] writing polite letters in hopes of getting change. …I’m not a college graduate, or a Woman’s Libber. I’m not radical or even liberal. I just want a break for the common people.”[9] Like many whose political yearnings and commitments were awakened in the crucible of the Sixties, Wolff sought a civic space, or sphere, outside of conventional left-right, Democratic-Republican politics. But she also wanted that space to be independent of cultural movements with a political valence. Although Wolff deliberately and consciously distanced herself from liberalism, her evocation of ‘the common people’ echoed Adler’s call for a common-sense philosophy based on universally accessible common experience. Wolff’s activism and great books-based thought existed in, and for, the shared public sphere.

While Wolff was no ‘intellectual’ and even exhibited traits of anti-intellectualism, she nevertheless exhibited some characteristics of a Gramscian organic intellectualism. She explicitly linked her mental and political empowerment to her own community of discourse, relaying that they asked about the Great Books reading group. Up to this point in the twentieth-century history of the great books idea, most claims about empowerment via that idea come from the top (e.g. Lubbock and the Workingmen’s College; Erskine and World War I soldiers; Everett Dean Martin, Adler, and the People’s Institute; Great Books Foundation reading group enrollee propaganda). Direct claims from great bookies like Wolff, as well as the aforementioned Shimer graduates and Malcolm X (mentioned in my book), are scarce as of the early 1970s—though more will come later through the work of Earl Shorris and his “Clemente Course in the Humanities.”[10]

Wolff, then, is a colorful, unique example of Shimer graduate Mary Caraway’s aphorism that “if a person is to be free, [s]he must be able to think.” The great books idea had inspired Wolff to live out, in a thoughtful fashion, her full responsibilities as U.S. citizens—as Adler and his community hoped. Yet she exhibited a personalized great books sensibility derived from her own reading and local experiences.

III.

Terkel’s attention to Mary Lou Wolff puts one in a Marxian and Gramscian frame of mind. While Wolff’s home work may not be a popular topic these days in labor history (in accordance with my limited knowledge of that field—i.e. Ruth Schwartz Cowan’s excellent work), and she’s not exactly indicative of any Denning-esque “laboring” of 1970s American culture, her experience demonstrates something of labor’s craving for theory. She desired a what I will call a ‘Gramscian organic intellectual climate’ that would help her think through, and act on, her living conditions. She achieved that climate, in part, through the great books idea. And specifically through the reading group format as championed by the Great Books Foundation, Adler, and his community of discourse. Wolff’s awakening, and her articulation of it to Terkel, indicate an heart-mind-and-soul engagement that gets to the heart of what I mean by a bottom-up great books sensibility.

In my next post I will explore how Dorothy Day’s great books sensibility, and how it manifest in the Catholic Worker movement. – TL

—————————————————–

Notes

[1] Clifford Geertz, Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology, 3rd ed. (New York: Basic Books, 1983), 75-76.

[2] I would like to thank Stephen M. Hageman

, history instructor at William Woods University, for first making me aware of Wolff’s story. Hageman has written about Wolff and others for his dissertation (working title), “Confronting Backlash, White Flight, and Urban Decline: The Catholic Neighborhood Movement and Community Organizing in White Ethnic Chicago, 1966-1990” (University of Illinois).

[3] Studs Terkel, American Dreams: Lost and Found (New York: W.W. Norton, 1980; reprint, NY: The New Press, 2005), 265–272; Cornelia Honchar, “Silent Housewife Leaves Kitchen to Fight City Hall,” Chicago Tribune, November 5, 1972, B6.

[4] Honchar, “Silent Housewife.”

[5] Terkel, 268-269.

[6] Honchar, “Silent Housewife”; Jon Hilkevitch, “Madigan Revives Crosstown Highway Talk ; Shelved since 1979, Project this Time would be Toll Road,” Chicago Tribune, February 21, 2007, 2C9; Peter Negronida, “300 Citizens Roast Officials on Taxes, Political Waste,” Chicago Tribune, October 14, 1972, S_B20; Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor, American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley – His Battle for Chicago and the Nation (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2000), 544-545.

[7] Sara M. Evans and Harry C. Boyte, Free Spaces: The Sources of Democratic Change in America, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 17–18.

[8] Honchar, “Silent Housewife.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] For more on Earl Shorris, see Riches for the Poor: The Clemente Course in the Humanities (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000) and New American Blues: A Journey Through Poverty to Democracy (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997).

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Tim, this is a great story. I’m really struck by some of Wolff’s phrasing: “another little bunch of women” proposed a Great Books program, and then “we all laughed” because “this is not that kind of a neighborhood.” There’s so much here, all mixed together — courage and aspiration bumping up against self-consciousness and self-doubt, a longing for broader horizons unfolding side by side with a reassertion of the ties of home (“home” meaning place/neighborhood, but maybe also relationships and social roles, the sense of themselves as a “bunch of women,” housewives, neighbors, etc.) It’s a neat moment she is describing.

I’m struck also by how she describes her reading: “This is the first time I, as an adult, ever discussed with other adults what the Declaration of Independence could possibly mean to me.” So much here too. Her emphasis on adulthood carries with it the implication that she had read this text before, in school, but also underscores how this reading was different — not imposed or assigned, but chosen, taken up willingly. And the end of that line — what the text “could possibly mean to me.” Here, I think, is where you see the contours of a larger sensibility. “What does this book/document/passage mean to me?” — that’s a particular, shared way of approaching texts that you might find in Great Books reading groups or neighborhood book clubs or home-based Bible studies too. A very different way of reading, a different hermeneutic, than that practiced and promulgated through other institutional structures — through school, church (or, some churches), university, and even through the formal organization of Great Books institutes or programs.

“What does it mean to me?” — that’s a tell, or a marker, for a certain sensibility, a certain “feeling for books,” to borrow Radway’s title if not her argument. That idea of reading would have become salient at a particular historical moment, and as the calling card of a “sensibility,” it would have left traces all over the place. I would be really interested to hear where else you find it in your researches.

LD: There is indeed a lot to unpack in Mary Lou Wolff’s interview with Terkel. The politics are muddled, and I know that my brief attempt above to untangle them is inadequate. But the bigger issues are related to gender. There’s a LONG history (as you know) of reading groups as gendered female. My citation of Evans and Boyte was an attempt to unpack that a bit—along the lines of consciousness-raising (though I didn’t use that term above). – TL

Wait — gender plays a role here? If you say so, Tim.

😉

But on reading groups, gender, and self-culture — one of our fab profs at UT Dallas, Erin Smith, has a book coming out soon, What Would Jesus Read?, which will look at Evangelical (and also, I believe, “heterodox” Protestant/generically “spiritual”) reading habits in post-WWII America. IIRC, she has a chapter on Oprah book clubs. In any case, I know the title will be of great interest to 20th c U.S. print culture/history of the book folks, as well as U.S. religious history folks, and I’m guessing it would be of value to your study of “Great Books culture” as well.

Okay, so my gender point was a bit obvious in light of your comment. My (personal/professional) problem with really getting granular on gender here is that I don’t know her family situation, neighborhood, and the full dynamics of her GB reading group. So I was hesitating to say too much

It’s clear, however, that the group empowered her and her friends, who clearly felt “little” and non-feminist (not a “women’s libber,” an interesting juxtaposition) and not radical as they positioned themselves against the “Daley Machine” (clearly gendered male). Wolff associated power with feminism, but she couldn’t embrace that association (despite the embedded ‘liberation’ in Libber). – TL

And thanks for the tip about Erin Smith’s forthcoming book. I’m sure we could enroll Kathryn Lofton in this conversation. Maybe I’ll send her this link. – TL