The following is an exchange between

The following is an exchange between Mark Edwards Cara Burnidge (co-chair of 2014 S-USIH conference committee) and Kathryn Lofton, the keynote speaker for the 2014 S-USIH conference. We are grateful to Professor Lofton for being willing not only to give the keynote but for thinking through her relationship to intellectual history in this brief exchange below.

1. Currently, you are completing several research projects. Could you give us a brief preview?

Two projects occupy my present research. First, I’m working on a statement about the Goldman Sachs Group. This will consider the history, training practices, and civic presence of The Goldman Sachs Group as a case for students of religion. This project reflects my ongoing obsessive interest in the relationship between economic life and religious culture. In my book about Oprah, I focused more on consumer practice as contributing to religious identity; in this project I think about financial management as a locus of religious knowledge.

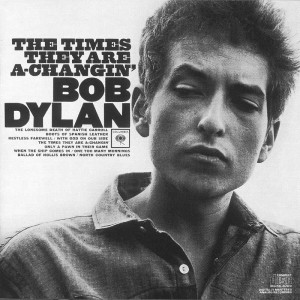

Second, I’m working on a short book that examines Bob Dylan as an orienting figure for American religious history since World War II. Here I want to think, in particular, of how incarnations of charisma become personalized allegories in modern media culture.

Second, I’m working on a short book that examines Bob Dylan as an orienting figure for American religious history since World War II. Here I want to think, in particular, of how incarnations of charisma become personalized allegories in modern media culture.

And third, I have for eleven years been meditating on this very particular example drawn from the archive of early fundamentalism, a Presbyterian pastor and university president named John Balcom Shaw (1860-1935) who was remitted from the in 1918 under accusations of sodomy. The case initially attracted me for the predictable prurient reasons, but over time the story has become much denser and stranger, something more about the end of theology than about the inauguration of the homosexual as a social type. But I have been lost in this material, frankly, and at times I despair that I’ll never find myself atop it. I have wagered many different theses, and shifted chapter outlines nine times.

This struggle reveals to me two things: first, writing revisionist history in a field of dense, capable monographs is not for the faint of heart; second, I don’t know yet what I truly want to say. So I pick up other projects alongside the Big Project as a way of trying to refresh my thinking amid the baseline gloom of dense documentary labor.

2. How do you see your work as a part of US Intellectual History?

I want to answer this question in a roundabout way. Which is to note that I referee a lot of manuscripts in religious history, and I review a lot of published books. And I’ve noticed about myself that I have pretty consistent peeves when I’m reading something. (I say this aloud in the hopes that maybe I’ll stop being so tediously repetitive in my complaining and move on to better critique!)

My first irritation is formalist: I hate it when I don’t think the author has reflected about the relationship between the structure of their book and its thesis. These two things — form and argument — are inextricable, and religionists should know this better than anyone!

My second related irritation is when authors don’t fight, strongly, to answer a “why” question in their work. I personally loathe when faculty press this as a “so what?” prompt, since I think “so what?” should be left to teenagers as a shirk of dialogue. To answer “why” something is as we have described it to be is our hardest, hardest work, and I have failed to do this in my own work, time and again, a point which Tracy Fessenden made in her spot-on critique of my first book. But we must do it. And I tend to think that the “why” is the intervention of the intellectual remarking upon the abstractions of the case. This is, to me, intellectual history, U.S. and not. It is the prompt to think conceptually about the case. And everyone, even if they slug in the material facts of labor history, should be in partial service to that command.

3. What do you see as the purpose/significance of Intellectual History as a realm of inquiry?

If Intellectual History is a bibliography of self-identified students of ideas, then I think it has a purpose of a certain expertise which we rely upon for its explanatory capability. I have read Perry Miller and Richard Hofstadter, David Noble and Martin Jay, David Hollinger and James Kloppenberg, and been quite simply floored by the ways those men (leaning gently, there, on the gender demographics) prove a profound relation between abstractions and material reactions, the way an idea engages and can create social facts. Those historians are experts because of their peculiar brilliant absorption in the metaphysical claims made and the lives that produce them.

If Intellectual History is a bibliography of self-identified students of ideas, then I think it has a purpose of a certain expertise which we rely upon for its explanatory capability. I have read Perry Miller and Richard Hofstadter, David Noble and Martin Jay, David Hollinger and James Kloppenberg, and been quite simply floored by the ways those men (leaning gently, there, on the gender demographics) prove a profound relation between abstractions and material reactions, the way an idea engages and can create social facts. Those historians are experts because of their peculiar brilliant absorption in the metaphysical claims made and the lives that produce them.

But if Intellectual History has significance it is not on the grounds of such expertise. It is only if Intellectual History proves that the intellectual is not an exclusive category — that is, if it proves that its premise is not a mere matter of expertise, but a practice of life shared by all — that it gains significance. Probably the best new work in this vein is Molly Worthen’s history, Apostles of Reason. Now, I don’t agree with Molly about everything that she argues in that book — this is the good stuff of academic debate — but I do agree with, and deeply admire her commitment to the democratization of the intellectual, the retrieval of it from NYRB stratospheres. Nobody who has had a thought (which is everybody) is removed from the archive of the Intellectual History.

But if Intellectual History has significance it is not on the grounds of such expertise. It is only if Intellectual History proves that the intellectual is not an exclusive category — that is, if it proves that its premise is not a mere matter of expertise, but a practice of life shared by all — that it gains significance. Probably the best new work in this vein is Molly Worthen’s history, Apostles of Reason. Now, I don’t agree with Molly about everything that she argues in that book — this is the good stuff of academic debate — but I do agree with, and deeply admire her commitment to the democratization of the intellectual, the retrieval of it from NYRB stratospheres. Nobody who has had a thought (which is everybody) is removed from the archive of the Intellectual History.

4. How do you conceive of US Intellectual History’s relationship to other fields and disciplines (including especially American Studies, Religious Studies, and Cultural Studies)?

I think historically the relation has been vexed and hierarchical. The cultural turn included, as one of its worst habits, a kind of reflexive populist snobbery toward Intellectual History, and this diminished enormously the intellectual consequence of many works that could have been better if only they hadn’t been so frightened of being associated with ideas (as opposed to movements, practices, habits, affects, or modalities). Yet at the heart of all the fields you mention is a central definitional drama (what is America? what is religion? what is culture? what is study?) that cannot evade intellectual history as practice and purpose if ever it is to be resolved. Put another way: Name a U.S. religious historian, and I’ll show you someone who is — whether they know it or not — practicing intellectual history.

5. Some consider the creation of specific subfields to lead to the marginalization of those areas of study. As a scholar whose works speaks across several subfields, do you think this is the case? More specifically, do you see the creation of a US Intellectual History subfield as a sign of intellectual history’s marginalization?

When I look at the past presidents of the AHA and OAH, it doesn’t seem to me that intellectual history is marginalized. But perhaps this is a lousy metric of centrality. I suppose I think the development of subfields is more about the development of expertise — the field exists in part to control (largely, I assume, through the proposition of graduate curriculum) what is proper to know. Given what I have already said about the possible reach of the concept Intellectual History, it seems right to me that a subfield forms; just when it could be Everything, the world rushes to specify its Something.

The unfortunate thing here isn’t the potential marginalization, but the canonization, which perhaps tends to lead to the reiteration of certain saints (like Martin Jay, for example) to the expense of other ideas of the intellectual or the historian. To take extreme examples, how many graduate students studying U.S. Intellectual History read either Jacques Derrida or Audre Lorde as components of their required curriculum? A safe argument could be made that both have had much stronger impacts on the history of ideas than Jay, yet Jay (who again, I think is masterful in his craft) is required reading.

The unfortunate thing here isn’t the potential marginalization, but the canonization, which perhaps tends to lead to the reiteration of certain saints (like Martin Jay, for example) to the expense of other ideas of the intellectual or the historian. To take extreme examples, how many graduate students studying U.S. Intellectual History read either Jacques Derrida or Audre Lorde as components of their required curriculum? A safe argument could be made that both have had much stronger impacts on the history of ideas than Jay, yet Jay (who again, I think is masterful in his craft) is required reading.

6. What US Intellectual History books or scholars influenced your scholarship most?

Besides those I’ve already mentioned, I would say that that Laurie Maffly-Kipp and Jackson Lears imprinted themselves upon me during my graduate student years (Laurie through her writing and pedagogical person, Lears through his occupation of my bookshelf) and continue to form my concept of the relation between social formation and intellectual argument. But there are so many in my peer group — like John Modern and Brendan Pietsch — who are working on or have written works I would call intellectual history, and I am regularly emboldened by their work.

7.I know it’s a bit early, but, if possible, could you share a bit about what issues you are most excited to discuss in your keynote address?

What I want to solve is whether pop music has a meaningful place in U.S. Intellectual History. Expect examples to be drawn from the discography of Mr. Dylan, Mr. Yorke, and Ms. Knowles, among others.

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Fantastic interview. Cannot wait for the conference. Great job, Mark and Cara!

I found myself copying and pasting little enlightening phrases from this article here and there. Flashes of brilliance, call it. But regardless how I feel about the work (or what she feels it is), the “that’s impressive” moment came when I realized, every time Cara starts a sentence with “If” … there’s a “then” in the middle. Mark of a thinker. I liked that “why” peeve too.

I meant Kathryn. It’s 5 oclock somethere

There has been an unfolding conversation on Facebook about Kathryn Lofton’s intriguing interview, much of it centered around two potentially contradictory ideas that she puts forward. These are, as identified and quoted by Andrew Hartman:

1) “It is only if Intellectual History proves that the intellectual is not an exclusive category — that is, if it proves that its premise is not a mere matter of expertise, but a practice of life shared by all — that it gains significance.”

2) “The cultural turn included, as one of its worst habits, a kind of reflexive populist snobbery toward Intellectual History, and this diminished enormously the intellectual consequence of many works that could have been better if only they hadn’t been so frightened of being associated with ideas (as opposed to movements, practices, habits, affects, or modalities).”

These two quotations generated debate about whether they were paradoxical—the first gesturing to a populist democratization that Lofton suggests is still required in intellectual history; the second seeming to take almost the opposite position as a critique of the populist anti-intellectualism Lofton views as present in historical inquiry after the cultural turn. Is there a need for still more democratization in the study of the intellect across broad sections of society (quotation one) or is there a need to recover intellectual life even if it exists at elite levels (quotation two?)? The debate touched on earlier debates and discussions on the topic of intellectual history’s boundaries that have occurred on this blog; and perhaps it also broke new ground (I’ll leave that judgment to others).

In any event, as requested by USIH’s fearless leaders here are my comments, transported through the magic of cut and paste from Facebook to the original USIH blog post comments section.

Note that these will read a bit out of context until the other commentators on Facebook (hopefully) post their engagements with Kathryn’s interview. But for now, here’s what I had to say:

Comment #1:

To me what Kathryn doesn’t say, though I suspect she’d agree, is that intellectual history, at its best, has sophisticated and nuanced modes of addressing the very (vexing) question of how ideas, power, equality, and hierarchy relate to each other.

Comment #2:

This is quickly written, so subject to tweaking and clarification (and continued critique and debate), but I think there are three positions lurking here: one is Nils’s and Ben’s insistence that we draw strong boundaries between thinkers who approach ideas in systematic ways (Kant) vs. the surfacing of ideas in other forms (poor Honey Boo-Boo, once again!)–in this position, so far as I can tell, one of the fears is that it’s a slippery slope from Honey Boo-Boo and Oprah to Roger Ailes, Zhadanov, and Goebbels as intellectuals; the second position is the one that Kathryn at once gestures toward and criticizes–she is arguing that intellectual history needs at once to be democratized in its sensitivity to the intellect in play across many settings, both systematic and less worked out, while at the same time she wants the field to avoid adopting reflex populist positions that are glibly and simplistically populist and anti-intellectual (I’m more in this camp, though I am willing to listen carefully to the concerns raised by Nils and Ben and others); the third position is an important one–to me it is that we can grant that there are different levels of systematic intellectual reasoning, but that there are also complex intersections among these levels of systematic thinking and more loose and even dodgy surfacings of intellectual activity (again Kant vs. Oprah), and that sometimes it indeed takes not a scalpel to discern them but rather new, more subtle ways of thinking about the intellect and how it moves around, cross-cuts boundaries; in other words to make the very kinds of moral and ethical inquiries that Ben sand Nils call for, to distinguish between, say, the intellectual (and ideological) workings of Oprah and that of Ailes (Goebbels, come on!) without falling back on hierarchies that seem, in their way, to reinforce other kinds of social, political, cultural inequalities that really are just elitist.

Comment #3:

PS Maybe position two and three are the same in the above?

Comment #4:

I think Ben makes a good point. We’re discussing all thus in the provisional space of interviews and Facebook posts. So all is understood as dialogue and (if Nils will grant us this! That’s a joke) *unsystematic* exploration of ideas Kathryn broached, ideas that continue long-running debates in usih land about the contours of intellectual history.