a review by Alan Wald

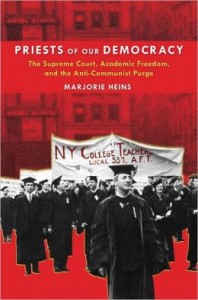

Priests of Our Democracy: The Supreme Court, Academic Freedom, and the Anti-Communist Purge

by Marjorie Heins

384 pages. NYU Press, 2013

Many professors in 2013 are teaching in colleges and universities episodically embroiled in controversies that run the gamut from the content of our courses and educational events on campus to the criteria used for tenuring faculty and admitting undergraduates to our institutions. Yet we are often woolly about the particulars of the legal notion of “academic freedom.” On a practical level, we may pride ourselves in being acutely mindful of the need to square our personal political commitments scrupulously with professional responsibilities, especially in our classroom comportment. But is that sufficient? Do we really have a conceptual understanding of potential threats to our livelihoods relative to our rights of freedom of expression and association?

Why doesn’t the First Amendment adequately protect faculty members from punitive job loss if we are performing our official duties well? Does the “freedom” in academic freedom refer mainly to the safeguarding of a teacher from retaliatory sanctions implemented by one’s own internal administration? Or is it about the shielding of the university itself from external pressures arising from the government, angry sections of the public, and business? Why have the courts failed to understand that there can’t be free inquiry if one is under the threat of losing one’s job for holding—or having once held—certain political views? Why does there appear to be an unconscionable distinction between our rights and those of high school teachers?

Curiously, as constitutional lawyer Marjorie Heins demonstrates in Priests of Our Democracy, the rulings that define the present legal framework of academic freedom as a special concern of the First Amendment do not go back to the foundational 18th century devising of the Constitution or the 19th century creation of the university system. On the contrary, the Supreme Court, which never used the term “academic freedom” before 1952, adhered to the view for over a century that free speech has nothing to do with the right to hold one’s job. The justices were blind to the fact that, in a capitalist society, one can be blackmailed into timidity and inhibition out of fear of being economically punished. The protections we have today, somewhat under renewed attack since 9/11, emerged a mere five decades ago from ruinous Cold War debates about “Communist subversion,” a pummeling of mostly Jewish teachers in New York City with relentless roundhouse jabs.

These were years when many of us, like fellow baby boomer Heins, were students in public school and then college. We later came to realize that that the range of acceptable politics in the United States had dramatically withered from the vibrant Popular Front culture of the pre-war era, and, as a generation, those of us in academia set out to insure breadth, complexity, and a critical edge in university life. Up until the culture wars of the 1980s, it seemed certain that things had changed fundamentally for the better, despite marring by occasional occurrences of over-zealous “political correctness.” But now one wonders if it was only in our imaginations that we had relegated the years of McCarthyite bullying and intimidation of teachers and scholars to the status of a dead dog among all enlightened people.

In her richly documented work, magnificently negotiating the many tripwires of an intricate story, Heins asserts that this McCarthyite political yesteryear has indeed not gone entirely away. What we are bequeathed is generally known as a sequence of Supreme Court decisions between 1952 (Adler v. the Board of Education) and 1967 (Keyishian v. the Board of Regents), and a popular persistence of ingrained habits of thought (such as a belief that faculty can easily corrupt the minds of students, possibly even more so if the teachers are conscientious scholars and fair-minded in the classroom). But the knot of subtleties of what really happened in the 1950s and early 1960s continue to shape the matrix of the cultural present for academics and students in ways about which many of us are less aware than we are about events of World War II and the Great Depression. It seems that Tom Irwin, the young teacher in Alan Bennet’s 2006 play The History Boys, got it right when he remarked, “There is no period so remote as the recent past.”

Heins insists that it is the inside story of the ambiguous legacy of this fifteen-year battle that remains critical to the here and now. Her contention is particularly buttressed by at least one mind-bending arguement of the narrative: The fight to establish academic freedom is not simply a battle of ideas but above all a story of the American Left. From the advent of the twentieth century, it was the efforts of radical professors to act humanistically in supporting labor rights and opposing war that ignited the first efforts by governmental bodies as well as university administrators (sometimes at the behest of business interests) to punish faculty (for example, Edward Ross and Scott Nearing) for speaking out in public. The first part of her book, “Prelude to the Deluge,” reviews this history up to the turning point of the Rapp-Coudert Committee (named for its chairmen) of the New York State Legislature from 1940 to 1942.

This infamous investigation of alleged Communist influence in publicly-funded higher education focused mostly on City College but included Brooklyn College, Hunter College, and Queens College. The Rapp-Coudert committee established an influential paradigm by its use of a private hearing with no legal counsel, no right to cross examine other witnesses, and no right to maintain transcripts of the proceedings. Since the Rapp-Coudert Committee had no mechanism to punish the targeted individuals on its own, there was only a short pause before the New York Board of Higher Education took the collaborative position that membership in the Communist Party, as well as a refusal to testify co-operatively, was grounds for immediate job termination. Forty faculty and staff were summarily fired.

The issue of academic freedom, in the sense of political opinions expressed outside the classroom and one’s freedom of association, became the common concern of teachers in both the public schools and in higher education right after World War II. At that time President Truman, the actual instigator of the anti-radical witch-hunt, issued his 1947 executive order calling for federal employees to be investigated for their loyalty. This inspired New York State to follow suit with its “Feinberg Law” (named after State Senator Benjamin Feinberg), which called for the dismissal of any teacher (or other public employee) simply for belonging to an allegedly “subversive organization,” mainly groups that were declared to be so by the U. S. Attorney General Tom C. Clark. Although the Communist-led New York Teachers Union was successful in challenging the Feinberg Law’s constitutionality in the New York State Supreme Court, Feinberg was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in a 6-3 decision in 1952 known as “Adler [after mathematician Nathan Adler, the first plaintiff listed alphabetically] v. Board of Education.” Following this, Adler himself and hundreds of other public school and college teachers, most of whom refused to answer questions about their political affiliations because they did not wish to name names and incriminate others, were variously purged.

This battle over Feinberg continued on the legal front, both locally and nationally, until someone decided to do something about it in 1963. A Shakespearian scholar named Harry Keyishian, who as a student in 1952 had protested the firings of economist Vera Shlakman and literature professor Oscar Shaftel (his advisor) from Queens College, was asked to sign an anti-Communist loyalty oath at the State University of New York at Buffalo. Keyishian and four colleagues simply refused, and were summarily fired. They then took their case to a very different US Supreme Court led by Earl Warren, which in 1967 rendered a 5-4 decision effectively reversing the 1952 Adler decision. Heins describes Keyishian and his associates as “ornery professors,” very much in the tradition of Adler, Shlakman, and Shaftel, although of a new (non-Communist) generation of Leftist rebels.

Priests of Our Democracy, a masterpiece of legal journalism, takes its title from a statement of Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who was not especially courageous in the 1950s but did dissent in the Adler case. He used the phrase that same year in a subsequent deliberation that successfully invalidated a “test [loyalty] oath” for professors in Oklahoma. Frankfurter argued that teachers deserved the widest latitude in expression because as “priests of our democracy” their special job was to “foster habits of open-mindedness and critical inquiry” (8). This opinion was in effect shared by justices William O. Douglas and (later) Earl Warren, and several pro-civil liberties decisions of 1957 were pivotal in undermining repression. Still, the majority of the court was mostly held hostage to two prevailing “climate changes” in national politics, first to the Right in the 1950s, and then to the Left in the 1960s.

The contradictory sequence of legal disputes in these two periods led to the establishment of the current form of academic freedom, still imperfect and with an uncertain future, with several heroes and villains as protagonists. But mostly Heins writes about ordinary humans with mixed motives and conflicting loyalties. She belongs to that recent school of radical scholars, represented by Yeshiva University historian Ellen Schrecker, who believe that it is better to treat the saga of the Left by candidly revealing the facts rather than hiding behind euphemisms and evasions. Many of those targeted by the Right were Communist Party members, or had been so in the past, and several lied to protect themselves, family and friends. Communism itself was a Janus-faced phenomenon; the teachers fought the good fight to improve the school system and eliminate racism, but such laudable values were bound up in near-unshakable delusions about the Soviet system. When pro-Commuist teachers marched in lock-step with the Party switch in political line at the time of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, they played directly into the hands of those who said Communist teachers were hypocrites and could not be trusted to think for themselves. After all, despite a different ideology and economic system, the USSR in its 1939 actions appeared to have an expansionist agenda coordinated with Hitler’s.

Some of those who refused to co-operate in the hearings had certainly quit the Party, or had never been much involved, and perhaps had grave doubts about Stalinism. But in the honorable act of refusing to name names, they found themselves handcuffed to a political movement adulating a police state nearly as brutal to its own population as Nazi totalitarianism. As a group, those resisting the Feinberg Law were more burdened by integrity than secret acts of disloyalty. But it would not be surprising to discover that the “free speech” values of the pro-Communists were in many ways as dogmatically circumscribed as those of their antagonists when it came to the rights of individuals believed (by Communist standards) to be anti-Soviet, racist, and anti-working class.

Some of the witch-hunters seem to have had the hearts of sharks, pathologizing dissent and pursuing decent people with a vengefulness that verged on the Biblical. But they saw themselves as soldiers in a moral crusade and were correct in judging Soviet Communism as a danger to international human rights. Nevertheless, once prisoners of “the metaphysics of Communist-hating,” they embarked on a slippery slope of undermining domestic freedom and supporting US international policies adversarial to colonial independence in Latin America, the Middle East, South East Asia, and elsewhere. U.S. liberalism was surely at its ugliest hour; many liberals failed to defend the Jewish teachers, even as Justice Hugo Black, a one-time member of the Ku Klux Klan, came firmly down on the side of Adler! The failure of Cold War liberalism, especially the “anti-Stalinist” variety, when actually put to the test, would understandably make this brand of politics abhorrent to the New Left that emerged just a few years later.

While Priests of Our Democracy is far from a psychological narrative, Heins captures some of the complex emotional drama of those who were targeted and purged. Freud was probably accurate that biographical truth will never be had beyond doubt, but Heins shows us a labyrinth of tangled lives that makes her story attention-grabbing and compelling. One never gets the sense that complicated or embarrassing issues are being sidestepped, or that some wool is being pulled over one’s eyes. In her telling, the Red Scare is not some inexplicable spectacle or monstrosity but grows out of comprehensible events, decisions, and accidents.

Heins concludes her book with a brief survey of some of recent controversies in academic freedom still entangling us in this painful past. The anti-radical offensive after 9/11 resembles the anti-communist crusade in that it is driven by forces whose objectives, like those of the Red-hunters, are broader than the eradication of the named target. In the 1950s the devil was supposed to be the Communist Party, and now it is “Islamic terrorism.” Nonetheless, just as a radical’s desire to “overthrow” existing socio-economic relations can mean different things to different people, so it has often turned out that one person’s “terrorist” is another’s “freedom fighter” (as the example of Nelson Mandela, also a former Communist, should remind us).

One may sign on to the anti-radical Zeitgeist, rebooted by the “war on terror,” due to reasons that are rationalized as legitimate national security concerns. Yet the resulting collateral damage of this emotional and ideological lurch to the Right encompasses what are primarily humane measures championed by the Left. In the 1950s these sometimes unintended casualties were mainly the rights of labor and anti-racism, while today they are more likely to be multiculturalism, affirmative action, choice for women, an end to sexual discrimination and racial profiling, the teaching of evolution as scientific truth, and free space for controversial ideas (including those that one hates). To the newly-emboldened activists of the Tea Party, fundamentalist, and neo-conservative movements, many of these appear subversive and to some they are un-Christian.

Yes, we thought we killed off McCarthyism in academe, but, like a zombie, it won’t stay dead because its characteristic habits of thought, nurtured by an element of legitimate fear, are available for service in what may be yet another political climate change. Heins writes: “As at other moments in our history, it is sometimes argued that the need for political loyalty trumps free speech, including—or especially—speech by teachers….A primary lesson of the history recounted in this book is that the American political system is all too vulnerable to political repression and to demonizing the dissenter, both on campus and off” (282). Academic freedom is never truly attained but must be assiduously guarded, and qualitatively enlarged, if it is not to lose ground. As the anti-Nazi Dutch scholar Pieter Geyl observed, “History is indeed an argument without end.”

At the University of Michigan, Alan Wald is the H. Chandler Davis Collegiate Professor, named in honor of the McCarthy-era political prisoner. His most recent book is American Night: The Literary Left in the Era of the Cold War (University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

14 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this very interesting review — interesting, and very timely for my own reading, as I am knee deep in the NY intellectuals.

I’m wondering if Heins addressed, even if only by way of introducing the chief focus of the argument, the divisions within university faculties over this issue. I guess I’m thinking specifically of people like Sidney Hook, versus people like Henry Steele Commager.

Thanks for this wonderful review. I’m very excited to read this book. I have two thoughts.

First, I think it is fair to say that we still do not narrate the rise of Marxist and New Left scholarship in the late 1950s against the background of state repression and the overlapping set of prohibitions and proscriptions in the humanities and social sciences after World War II; we do not attend to the early interventions of Genovese, Weinstein, Sklar, et al as knowledge produced under considerable duress.

Second, I wonder how many key figures in the intellectual history of the postwar Left are children of Jewish teachers who lived through McCarthyism. Among my professors at Santa Barbara, I know that Dick Flacks was shaped by this experience, as was George Lipsitz. It would be valuable to think about this further as a historical variable.

The justices were blind to the fact that, in a capitalist society, one can be blackmailed into timidity and inhibition out of fear of being economically punished.

The Framers would have found that idea laughable. Besides, the only truly courageous speech is that for which you’re willing to take the consequences.

Man up. Like The Nuge.

http://www.nhregister.com/articles/2013/07/31/news/new_haven/doc51f9d97d0e84c435274862.txt

Just tacking onto Kurt’s comment above, you can add Eric Foner to this cohort: “Shortly before I was born, my father, Jack D. Foner, and uncle, Philip S. Foner, both historians at City College in New York, were among some sixty faculty members dismissed from teaching positions at the City University after informers named them as members of the Communist party at hearings of the state legislature’s notorious Rapp-Coudert Committee… A few years later, my mother was forced to resign from her job as a high school art teacher” (“My Life as a Historian,” in Who Owns History? Rethinking the Past in a Changing World {New York: hill and Wang, 2002}).

For proper context, Andrew, we should note that this particular “Red Scare” was not our “McCarthyism,” but in 1940-42, in the wake of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. As a result, the Communist Party USA pivoted from opposition to Hitler and fascism to a call for “neutrality” in Europe.

CPUSA membership was quite tied to bloody world events, not just abstract political theory. Poland was invaded and carved up as a result of the pact: we didn’t know it yet, but the Second World War had just begun.

Of course, errors and excesses such as McCarthyism are easy targets, but they don’t directly bear on the point. Foner’s phrasing might leave some people with the impression that the dismissed faculty [some resigned] we not members of the CPUSA, that this was a “witch hunt.” However, that’s accurate only insofar as some were indeed witches, that is, some were indeed Communist Party members.

Two questions arise, first the thought experiment about how far we’d go to defend the “academic freedom” of racist advocates of say, apartheid. Or the case of Nobel prize winning scientist

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn12835-james-watson-retires-amidst-race-controversy.html

whom the academy sent on his way.

The second is similar to the first but more on point, since City College was a taxpayer-financed institution–whether there’s a natural [god-given?] right to be paid by the American government to be an apologist for murderous tyranny such as communism/Sovietism/Maoism. Does the Constitution demand, or should it demand, that the US Government subsidize the rope to hang it with?

From the comfort of our 21st century armchairs–where in reality it’s pritnear impossible for even a radical Marxist to be dismissed from the academy (or a racialist like James Watson to enter it), this whole discussion is indeed an abstraction. We fancy ourselves back in the good old days of McCarthyism, or of Bull Connor, or of the Vietnam War, where we’d have been beacons of moral clarity, intellectual fairhandedness, and great personal courage, freely risking all for What is Good and What is True.

But this moralistic kabuki isn’t all that impressive 50 or 100 years later, armed with historical hindsight, where we’re always on the side of the good guys, the winners of intellectual history. Look, we came through clean–Communism was no threat after all, just a bogeyman of The Powers That Be!

In the 1950s the devil was supposed to be the Communist Party, and now it is “Islamic terrorism.”

LATE ADD, today 8/5/13:

US closes 21 embassies

Threat of “Islamic Terrorism” Blamed

So it goes.

Tom, I’m not sure if you’ve read Ellen Schrecker’s work on McCarthyism, but I’m presuming you read Alan Wald’s post above, which clearly links the Rapp-Coudert committee to later McCarthy-era purges and which, in reference to Schrecker, addresses completely the objections you raise.

Acknowledged, Andrew, followed by the inevitable BUT. The thesis is still always McCarthy, therefore x, never Julius Rosenberg therefore…

A link to possible real-world events is customarily missing, as though it’s always an abstract question of intellectual freedom.

As we see, the lesson is now that “Islamic terrorism” is the bogeyman put forth by the Powers That Be,

The anti-radical offensive after 9/11 resembles the anti-communist crusade in that it is driven by forces whose objectives, like those of the Red-hunters, are broader than the eradication of the named target.

where the essay devolves into the usual featureless indictment of its own bogeyman, the faceless “offensives” of the benighted (read: happily, not the author or his unbenighted reader. 😉

The irony of the US closing a couple dozen embassies today because of the aforementioned scare-quoted “Islamic Terrorism” required noting, I hope you agree. FTR, I say this as one who was rather in a agreement that al-Qaedaism has/had been largely headed off since 9-11.

But as the Venona Papers revealed the Commies really did have something going in America afterall, “common wisdom” is often neither.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/venona/intercepts.html

Until the Venona revelations in 1995–50 years later!–the common wisdom among the many of the unbenighted was to defend the Rosenbergs.

Believe me, I’d prefer that none of these witches and bogeymen were real. That would make it all easy.

And BTW, I thought the biggest recent failure of “academic courage” [besides in re Charles Murray] was Ward Churchill. It couldn’t have come at a more inappropriate moment, but his “Litlle Eichmanns” argument is quite tenable.

Thx for the reply.

Excellent review. I wonder if Marjorie Heins discusses anti-intellectualism in the academy as a larger, integrative topic for those opposed to Communism? Or perhaps the tension between legal practitioners/professionals and those intellectuals concerned with chasing ideas (i.e. the ancient tension between praxis and theory) in the context of Communism?

Random discussion addition:

In his history of academic freedom in America The Metaphysical Club, Louis Menand writes, “Coercion is natural; freedom is artificial.” The tenure system is an elaborate construction.

From here.

I thought that was an odd description of The Metaphysical Club, no?

To piggy-back on Andrew and Kurt: I’d go so far as to say that the political valence of the New Social History was shot through with a fundamental defensive quality that was the product of Cold War repression. The project of disproving the American liberal consensus was bound to be most compelling to people nursing the wounds of forced quiescence.

Just consider the names you associate with the founding generation of the New Social History. To take a stab: David Brody, Natalie Zemon Davis, Eric Foner, Linda Gordon, Herbert Gutman, David Montgomery, Gerda Lerner, Eugene Genovese, Nathan Huggins, Nell Painter, Vicki Ruiz, or Joan Wallach Scott (in her initial iteration). These were not suburbanite middle-class left-bohemians, but people bearing living memories of migrant proletarian neighborhoods and working-class radicalisms. Take the dedication of Ruiz’s Cannery Women, Cannery Lives: Mexican Women, Unionization, and the California Food Processing Industry, 1930-1950: “In memory of my grandfather, Albino Ruiz, beet worker, coal miner, Wobblie.” Or, as Linda Gordon put it simply enough in her Visions of History interview: “My parents were leftists, and Jews, and immigrants, and rather poor.” Agency and hegemony, the thematic concerns of this generation of historiography—borrowed from its two crucial methodological figures, E.P. Thompson and Gramsci—reflect these social origins. On the one hand, the dominant preoccupation with ordinary people’s agency bespeaks the centrality of working-class movements in forging these historians’ worldview. On the other, the concern with hegemony, the lingering question of “why no socialism,” reveals an anxiety about the permanence of the defeat of the Popular Front, I think, and beneath that, a pained relationship with the question of ethnic assimilation.

“In the 1950s the devil was supposed to be the Communist Party, and now it is “Islamic terrorism.”

Though it is possible to view the communist movement, or the Communist Party, in terms of the annihilation of the U.S. resulting from a nuclear holocaust, I don’t think this is the most politically thoughtful way of thinking about communism. Communism posed a political threat to the U.S. because it actually presented an alternative social vision of how to organize society differently. However much we might like to disparage the form the actual reality of the experiments in socialism assumed in Russia and elsewhere, no one can deny that the Soviet Union, in particular, represented a radical alternative to the capitalist U.S., a fact evident in the wide support the Communist Party USA enjoyed in the 30s and 40s. By contrast, Al-Qaeda is a reactionary fringe group with no coherent social vision nor interest in vying for political hegemony. That’s all to say, I don’t think it is analytically useful to think of communists as zealots on par with religious fanatics. I prefer Michael Denning’s sober treatment of fellow-travelers in his excellent book on the Popular Front to the simplicities peddled by Richard Crossman’s The God That Failed. I wish that Alan Wald, given his extensive research into the communist movement and its intellectuals, had pushed against the false equivalence of equating the communist movement as a latter-day counterpoint to today’s terrorist cells. In regards to the political concerns animating the U.S.’s foreign policy approach to terrorist groups, which is geared solely towards execution, the U.S. government, in its erstwhile struggle against communism, had to set up front organizations to engage the Soviet Union on a war of position, a testament to how seriously the U.S. felt threatened politically.

Luis: I wonder if a “first as tragedy, second as farce” model would make the countersubversive/anti-Islamist spirit of today a viable repetition of an earlier anti-communism? Exhibits: the massive interest among right-wing legal and political types in “creeping sharia”; the rationales proffered by liberal defenders of NSA snooping like David Simon and Kurt Eichenwald (perfectly ADA-esque); the logic at the heart of shows like 24 and Homeland.

Communism and Islamism have murder in common, as well as presenting their hegemony as a cure for what ails the human condition. Sometimes a comparison works just fine on the first level–every analogy need not be stretched to breaking.

What they also have in common is

“In the 1950s the devil was supposed to be the Communist Party, and now it is “Islamic terrorism.”

the reaction on the part of some folks to minimize—if not ridicule—concerns about this kind of stuff. [I personally am not terribly concerned about the Muslim Menace in America, but in other western countries I’m not so sure.]