The following is the final installment of Kurt Newman‘s guest posts on “Pragmatism and the Class Politics of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.’s Copyright Jurisprudence.”

Part One… Part Two… Part Three

Part Four: “Without Distinction: Pragmatism and the Class Politics of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.’s Copyright Jurisprudence, Concluded”

I’m very grateful for Andrew Hartman’s generosity in allowing me to air my ideas out here, and for the hospitality shown to me by this blog’s readers and contributors. Here is the final section.

Heresy, Yes—Conspiracy, No

The task that remains is some reflection on the class politics of Justice Holmes’s pragmatist innovations in the field of copyright jurisprudence. First, we should note that while Holmes’s embrace of “aesthetic relativism” dovetailed with an emerging corporate capitalist consensus, there is no “base-superstructure” dynamic to be found here. Holmes’s turn to “aesthetic relativism” was not a foreordained outcome, nor was it dictated, in any straightforward way, by the perceived needs of capital.

The task that remains is some reflection on the class politics of Justice Holmes’s pragmatist innovations in the field of copyright jurisprudence. First, we should note that while Holmes’s embrace of “aesthetic relativism” dovetailed with an emerging corporate capitalist consensus, there is no “base-superstructure” dynamic to be found here. Holmes’s turn to “aesthetic relativism” was not a foreordained outcome, nor was it dictated, in any straightforward way, by the perceived needs of capital.

There were as many commercial motivations to limit copyright in popular culture’s mass reproduced texts (which could be heard loudly from piano roll manufacturers, for example, who wanted to sell Sousa marches without having to pay Sousa any royalties, or from lithographers like Donaldson, who wanted to be able to freely copy popular designs) as there were pressures to modernize copyright. No one, in 1903, knew that the Hollywood studio system and national network radio lurked around the corner. In other words, while class discourse suffuses the arguments and analyses at the heart of the Bleistein case, we would do better to think of Holmes’s pragmatist innovations as class heresy rather than class conspiracy.

Class heresy, because given Holmes’s Brahmin background, a betting person in 1902 might have guessed that in Bleistein Holmes would either embrace a (“left”) critique of emergent mass culture, or a (“right”) turn to a defense of tradition and the preservation of a high threshold for “originality” in copyright law, rather than insisting, as Holmes did, that “the taste of any public is not to be treated with contempt.”

For context, we turn to Daniel Czitrom’s classic 1982 study Media and the American Mind. Czitrom reminds us that in the period immediately preceding the Progressive Era, the dominant discourse on “culture” centered around an Arnoldian defense of refinement and “self-tillage” against the perceived barbarism of the rabble. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, for example, wrote in 1867: “Culture is the training and finishing of the whole man, until he sees physical demands to be merely secondary, and pursues science and art as objects of intrinsic worth.” For Higginson, Arnold’s attacks on American middle-class philistinism hit the nail on the head: the US lacked “an atmosphere of sympathy in intellectual aims [1]”

American culture was the world of vulgar materialism (“the material or the sensational or the hysterically emotional,” as A.A. Stevens wrote in Harper’s in 1903) against the noble and elevated pleasures of aesthetics. It was not uncommon for cultural commentators to point to the need for a leisure class in order for an authentic American culture to finally develop. As Czitrom notes, advocates of the doctrine of culture “perpetually worried about its degradation of their audience, the educated middle and upper classes… The transformation of an ideal process into a mere commodity deeply troubled the upholders of culture.”

American writers, Czitrom observes, frequently struck Arnoldian chords. For example, Charles Dudley Warner in 1872 wrote: “Unless the culture of the age finds means to diffuse itself, working downward and reconciling antagonisms by a commonness of thought and feeling and aim in life, society must more and more separate itself into jarring classes, with mutual misunderstanding and hatred and war.” The educated man thus had a responsibility to the masses: “His culture is out of sympathy with the great mass that needs it, and must have it, or it will remain a blind force in the world, the lever of demagogues who preach social anarchy and misname it progress.” In 1892, F.W. Gunsaulus insisted that culture was needed to teach laboring men that the accumulation of wealth by the few was natural, and to fill the worker’s brain with “noble ideas and impulses.” Alfred Berlyn wrote (in language that should call to mind the debates around Bleistein): “The restless rush of present day life, its constant distractions, its perpetual movement, its ubiquitous newspapers, with their ever shifting kaleidoscope of events and interest—these things are inimical to the contemplative mood in which alone the companionship of good books can be sought with profit.”

At the same time, the elite impulse to strengthen a traditional “highbrow”/“lowbrow” cultural split was, as we saw in Part 3, consolidated in a series of copyright cases after the landmark Jolli v. Jacques. This was the effluvium in the air in bourgeois metropolitan America at the turn of the century, and its museums, universities, and local cultural societies. The influx of immigrants, rise of Jim Crow, and advent of social Darwinism all contributed to the coarsening of elite commitments to protecting Western art’s noble monologue from the screaming noise of plebeian expression and mass reproduced commodity culture. It was not Holmes’s decision, but Justice Harlan’s dissent in Bleistein (which consisted mainly of affirming the Circuit Court decision of Justice Lurton, some of which is reproduced below) that typified the dominant strain of bourgeois consciousness:

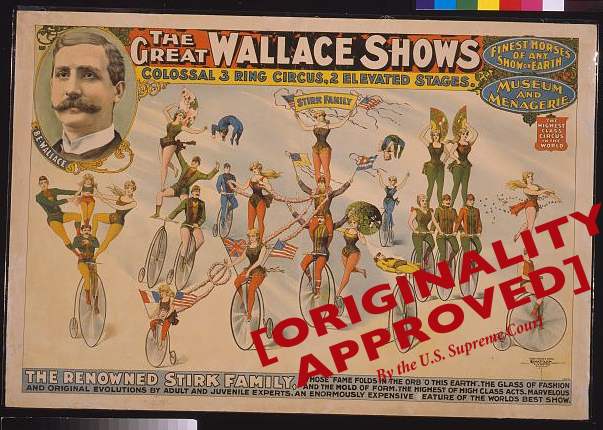

What we hold is this: That if a chromo, lithograph, or other print, engraving, or picture has no other use than that of a mere advertisement, and no value aside from this function, it would not be promotive of the useful arts, within the meaning of the constitutional provision, to protect the ‘author’ in the exclusive use thereof, and the copyright statute should not be construed as including such a publication, if any other construction is admissible… It must have some connection with the fine arts to give it intrinsic value… We are unable to discover anything useful or meritorious in the design copyrighted by the plaintiffs in error other than as an advertisement of acts to be done or exhibited to the public in Wallace’s show. No evidence, aside from the deductions which are to be drawn from the prints themselves, was offered to show that these designs had any original artistic qualities. The jury could not reasonably have found merit or value aside from the purely business object of advertising a show, and the instruction to find for the defendant was not error (emphasis added).

Without Distinction: Rancière Against Bourdieu on Politics and Aesthetics

The final question, then, insinuates itself: what was at stake in Holmes’s deferral of both the mainstream “left” and “right” positions on culture, copyright, and new technologies? The usual analytical impulses here would lead us to the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, and to Bourdieu’s proposal that processes of cultural distinction serve as the primary mechanisms by which class divisions are reproduced. A Bourdieuan interpretation of Bleistein would likely turn on the “secret” motivations underlying elite projects to enshrine traditional aesthetic culture in the public sphere as an insidious labor of pacifying the masses and ratifying class hierarchies. Holmes’s pragmatist insistence that “the taste of any public is not to be treated with contempt” would be a trick of some sort—either to congratulate the elite domain of “authorship” by letting in a token representative of the demotic arts, or to usher in further immiseration of the working class by opening the floodgates to an oppressive commodity culture.

In such a reading, of course, the house always wins. That should make us nervous. We recall, after all that Walter Benjamin’s dwarf who lurked within the “automaton” and ensured that the “machine” would always best its human competitors was named “historical materialism.” Are we really willing to sign off on all of the presuppositions that ensure that the house always wins? Is the realm of the aesthetic really just a laboratory for class reproduction? If so, why are aesthetic practices so central to proletarian dreams of “eight hours for what we will?” Was the spread of demotic commodity culture in the indeterminate urban spaces of the early twentieth century really, in all of its dimensions, a tragedy for the working class? If so, how do we explain Nan Enstad’s “ladies of leisure,” who sought pleasure in cheap shoes and hats and the nickelodeon against the finger-wagging of trade-union officials and Progressive reformers?

In light of these concerns, we are going to swerve away from Bourdieu, and instead seek grounding in the work of one of Bourdieu’s most diligent critics, Jacques Rancière. A Bourdieuan reading of Holmes’s copyright jurisprudence would tell us nothing that we do not already know. Reading Holmes with Rancière, in contrast, allows us, I think, to see something new.

Reading Rancière

Who, readers may be asking, is Jacques Rancière? A good question. Rancière was born in 1940 in Algiers, and as a young philosopher was part of the group surrounding Louis Althusser; Rancière contributed a chapter to the classic structuralist Marxist text Reading Capital (1968). Rancière then took up a teaching post at the University of Paris VIII, where he taught until 2000. After breaking with Althusser, Rancière turned to research in the historical archives, producing an extraordinary study of nineteenth century worker-intellectuals, The Nights of Labor (1981). As a hybrid philosopher/historian, Rancière occupied a unique position, given the tension we tend to associate between English Marxist history and French Marxist theory in the 1970s. Rancière participated in British debates around the “new social history” in the comparatively theoretically cautious environs of the History Workshop Journal, but was also was a part of the more radical and theoretically experimental milieu around Deleuze and Foucault in Paris. While Rancière steadily produced elegant studies of politics and literature throughout the 1980s and 1990s, it has been over the last several years that his impact has really been felt, in dedicated journal issues, conferences, and edited anthologies of critical considerations of his work.

As Peter Hallward explains, Rancière’s project is really an argument with Western philosophy’s “inaugural attempt to distinguish people capable of genuine thought from others who, entirely defined by their economic occupation, are presumed to lack the ability, time, and leisure required for thought.”[2] Most hateful to Rancière is the way in which such an ordering of the social field congeals into the imperative: “To each type of person, one allotted task: labour, war, or thought.”

What is missing from this kind of vision of difference and distinction is the possibility of “heresy” (for Rancière, the “displacement” of the speaker and “disaggregation” of the community so that a new arrangement of places and persons may be initiated), in particular that modern “democratic heresy” incarnated by the “arrival upon the historical stage of a popular voice that refuses any clear assignation of place, the voice of the masses of people who both labor and think.” This intellectual investment in “heresy” connects Rancière’s work on aesthetics to his work on politics. In Disagreement (1995), Rancière suggests that the “supervision of places and functions” at work in many strains of philosophy is also at work in a certain form of politics—“policing”—that is now dominant in the ostensibly democratic liberal-capitalist West. Under such a distribution of power, the key moments—in fact, the only ones that merit the name of “politics”—are those “events” that “allow a properly anarchic disruption of function and place, a sweeping de-classification of speech.” The “democratic voice” belongs to “those who reject the prevailing social distribution of roles, who refuse the way a society shares out power and authority… (and) deregulate all representations of places and portions.”

From this joint interest in the linked operations of politics and aesthetics, Rancière explores modernism’s “aesthetic revolution,” or as Hallward puts it: “the move from a rule-bound conception of art preoccupied with matching any given object with its appropriate form of representation (the basis for a secure distinction of art from non-art) to a regime of art which, in the absence of representational norms, embraces the endless confusion of art and non-art.” In this “aesthetic revolution,” the main thrust of art is the increasing democratization of the realm of representation: democratization at the level of representation and subject matter, of what can and what cannot be art. Here, the connections to Bleistein and its pre-history should be obvious. The affirmation of a circus poster as a text worthy of copyright is not, in Rancièrean terms, merely a banal moment in legal history, nor the sign of the degradation of culture at the hands of the forces of commodification. On the contrary, the political importance of Bleistein lies in its capacity to level illegitimate hierarchies, to render inoperable Aristotle’s (aesthetic) distinction of humans from animals as a sorting out of who is capable of speech and whose vocal expressions are mere barks, meows, and other illegible noises. If Holmes’s pragmatist innovations pointed to the notion that “everyone is an author,” then that would mean that the line between speech and noise would have to be redrawn—the very definition, for Rancière, of a political “event.”

Rancière contrasts the “aesthetic revolution” to the tenets of “orthodox modernism,” which underwrite efforts to restore a strict barrier between (non-representational) art and non-art. In Rancière’s frame, “orthodox modernism” is an initiative that “can only figure… as complicit in the perpetual attempt to restore traditional hierarchies, to return things to their officially authorized place, to squash the insurgent promise of democracy.” If the reader discerns here a willingness, on Rancière’s part, to throw out Brecht, Benjamin, Adorno, and Clement Greenberg in the name of a more egalitarian aesthetico-political theory, well, then, the reader is entirely correct. For Rancière, most of Western Marxist aesthetics is a bizarre recapitulation of the conservative attacks on Balzac and Flaubert at the time of the publication of their landmark novels. Like James Livingston—who happily tosses out the entire Marxist category of “reification” (and the related notion of “false consciousness”) for similar reasons–– Rancière pragmatically proposes that we owe no continuing debts to the theoretical legacies of baronial Europe.

For Rancière, no one better personifies the perverse tendency of “Marxists” to affirm the Platonic principle of “To each type of person, one allotted task: labour, war, or thought” than the late French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Much of the literature on Rancière’s dispute with Bourdieu centers on a conflict over primary and secondary education reform in France in the 1980s, which is not irrelevant to our project, but not nearly as salient as Rancière’s critique of Bourdieu’s seminal text Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (completed in the 1960s, published in France in 1979, and in English translation in 1984).[ 3] Distinction, a curious, collage-like work, combines reflection on empirical sociological research into variations in cultural taste up and down the axis of class with philosophical musings on the nature of social reproduction.

In his most focused critique of Distinction, Rancière begins with a proposition concerning the politics of aesthetics: “aesthetics is not the theory of the beautiful or of art; nor is it the theory of sensibility.” Rather, aesthetics is a “historically determined concept” that “designates a specific regime of visibility and intelligibility of art, which is inscribed in a reconfiguration of the categories of sensible experience and its interpretation.” This is the new type of experience systematized by Kant in the Critique of Judgment. Aesthetic experience, for Kant, implies “a certain disconnection from the habitual conditions of sensible experience.” Because art scrambles the usual circuits of desire and valuation, art always implies “a certain suspension of the normal conditions of social experience.” The Kantian rendering of this alternative modality of experience emphasized the key role of “disinterest,” a “will to ignorance”—including, crucially, ignorance regarding the labor inputted into artistic objects, or extracted from workers in order to erect monuments to culture–– written into aesthetics itself.

This “will to ignorance,” Rancière writes, “has not ceased to provoke scandal.” Rancière then turns to Distinction: “Pierre Bourdieu has consecrated six hundred pages to the demonstration of a single thesis: that this ignorance is a deliberate misrecognition of what the science of sociology teaches us more and more precisely, to grasp the fact that disinterested aesthetic judgment is the privilege of those alone who can abstract themselves—or who believe that they can––from the sociological law which accords to each class of society the judgment of taste corresponding to their ethos, that is, to the manner of being and of feeling that its condition imposes upon it.” In Distinction, Bourdieu merely reiterates what Plato proposed in The Republic: “Artisans cannot be occupied with the common matters of the city for two reasons: firstly because work does not wait; secondly, because god has put iron in the souls of artisans as he has put gold in the souls of those who must run the city.” Both Bourdieu and Plato end up confirming a certain double bind: “ (the artisans’) occupation defines aptitudes (and ineptitudes), and their aptitudes in return commit them to a certain occupation.”

It is this arrangement, Rancière writes, that aesthetic experience “deregulates.” Aesthetic experience “eludes the sensible distribution of roles and competences which structures the hierarchical order.” In his formalist attempt to uncover the secret class meaning of every aesthetic preference, Bourdieu wishes to reveal, once and for all, that aesthetic experience is an illusion, that its suspension of rules and roles is a trick of interpellation and false consciousness. Bourdieu, Rancière suggests, ratifies a kind of extreme condescension and conservatism in his treatment of working-class subjects as unknowing participants in the system that maintains their very subjugation. If only the workers could see the man behind the curtain—recognize, in other words, that aesthetic experience is simply a lie concocted by elites––they would be free both to enjoy their own self-contained cultural traditions and to shake off their internalized sense of class inferiority.

For Rancière, this is all nonsense. It is not by way of some Verfremdungseffekt that the working-class viewer is shaken out of her false belief in art-as-“disinterest”; it is by participating in art-as-“disinterest” that the working-class viewer invalidates all of the bogus hierarchies of class and distinction. The realm of the aesthetic, for Rancière, is precisely the location in which the strict mapping of people to places and functions (as in sociology and statistics, the origins of which can be traced back to rather brutal technologies of the “science of the state”) is refused.

“Bourdieu’s polemic against aesthetics is not the work of one particular sociologist on a particular aspect of social reality,” Rancière writes. Rather, it is structural. Sociology in general suffers from an inherent tendency to deny the provisionality and alterability of class relations. Bourdieu is a particularly important example, however, because his work so manifestly attempts to map the tastes that correspond to the various class positions.

The questionnaires used by Bourdieu in Distinction, for example, are set up to ensnare the unwitting subject. A typical “agree or disagree” type of question proposes: “I love classical music, for example the waltzes of Strauss.” Working-class interviewees attempting a “false positive” will, the questionnaire designer presumably guesses, be caught in this trap (which is that, for real connoisseurs of classical music, Johann Strauss does not qualify as a “serious” composer). “It is clear,” Rancière writes, “that the sociological method here presupposes the result it was supposed to establish.” In other words: there might be something to discover about working-class subjects and their engagement with art, culture, and music via sociological means; but Bourdieu’s question-begging procedures insure that a certain kind of prescreened knowledge about class and culture will be inevitably be confirmed.

In this sense, Rancière argues, sociology is essentially fighting a continuing battle against the French Revolution and its disordering, leveling, indeterminate democratic potentials. This is true not just of the reactionary or statist heirs of Comte and Durkheim: even Marxist sociologists have retained a strange fidelity to sociology’s concern with the fractures and divisions brought about by “philosophical abstraction, protestant individualism and revolutionary formalism.” As Martin Jay demonstrated in his classic Marxism and Totality (although he might well disagree with my use of that work here), Western Marxism, no less than conservative social science, sought to reconstitute the social fabric such that—in Rancière’s terms–– “individuals and groups at a given place would have the ethos, the ways of feeling and thinking, which corresponded at once to their place and to a collective harmony.” And while today, of course, this organicism is no longer regnant, the quest to understand “the rule of correspondence between social conditions and the attitudes and judgments of those who belong to it” remains in evidence. This is especially problematic politically if we want to see aesthetic experience not as the source of social order, but rather as among the most potent sources of productive social disorder, antagonism, unrest: “the division of the body politic within itself.” In the final analysis, sociology’s war on Kantian aesthetics ends up settling on a marriage with Plato’s ethics. “What sociology refuses,” Rancière writes, “is that inequality is an artifice, a story which is imposed.” Sociology wants to claim that inequality is an incorporated reality in social behavior, and “wants to claim that what science knows is precisely what its objects do not.”

Holmes After Rancière after Livingston

There are many connections to make here, and I worry that it is only my lack of sitzfleisch that is keeping me from patching through all of the calls. But I think the reader can likely do that work better than I can, at this point. Rancière, like Livingston, inveighs against a certain tragic rendering of the evolution of capitalism (in Rancière’s case, taking aim at Bourdieu-the-tragedian) and proposing, instead, the “comic” perspective on historical change advocated by Kenneth Burke in Attitudes Toward History. The enemies of egalitarian and emancipatory progress are not superhuman forces, but all-too-human vices—in particular, ruling elites’ arrogance, vainglory, and insistence upon the embodied inferiority of the subjugated (what Andrew Sullivan celebrated as the truth of “human biodiversity” in his enthusiasm for The Bell Curve). What interests Rancière, and what interests me, are those moments that disrupt these fantasies and redraw the map of the sayable and the thinkable. These moments reflect the particular historical contours of class antagonism in a given time and place, but they are not necessarily initiated—at least in the immediate term––by bottom-up resistance and revolt. This, I think, is another key insight that Livingston provides on the history of the Progressive Era: we need to be a little more Hegelian, a little more attentive to the “cunning of history,” before we accept the Populist or Sombartian narrative of declension. Shoals of roast beef, after all, aren’t anything to sneeze at. The legal adjournment of a certain elite tendency to link the inherent inferiority of the masses with the anathematization of both plebeian expression and mass reproduced commodities likewise should not be dismissed as yet another preprocessed, “always already” moment of failure and defeat

In conclusion: I have proposed that the culture of pragmatism, in Livingston’s sense, was the crucial context for the development of Holmes’s copyright jurisprudence, and that cases like Bleistein can tell us some important things about the way class discourses functioned in Progressive Era efforts to regulate aesthetic expression. I have put this essay together in the way I have in order to argue that when Holmes admitted circus posters into the world of authored texts, he was doing something different than simply letting a few more participants into the closed world of culture, or more insidiously, enacting a kind of “repressive desublimation” by offering token recognition in order to ensure that the system of class hierarchy could function all the more efficiently.

If we understand Holmes as a pragmatist, I think we can make the case that in decisions like Bleistein, Holmes straightforwardly refused the Platonic or sociological tendency to map the social field in a neat set of one-to-one correspondences. With Livingston, we can see how that epistemological preference for one-to-one correspondence, for strict correspondence of signifier and referent, was also at work in Populist political and economic theory, and in the simple supply-and-demand, wages-fund understanding of capitalism rejected by pragmatist marginalist economists. Similarly questioning orthodoxy, Holmes insisted on a pragmatic indeterminacy regarding the questions of who was a worker, who was an author, and how those roles could be simultaneously embodied in a single subject. Holmes was no saint, and neither he, nor Peirce, nor James, was entirely free of the anti-democratic prejudices of elite US culture. In some areas of law, as Corey Robin has recently reminded us vis-à-vis Holmes and the “clear and present danger” doctrine (and, of course, in the awful “three generations of imbeciles is enough” ruling of Buck v. Bell, not to mention Holmes’s undistinguished record on civil rights and the evolving abominations unfolding in the South in the first decade of the twentieth century) Holmes was infamously blinkered. There were limits to Holmes’s vision, and prejudices inscribed in the sources from which he drew: Peirce was a racist; James, while a mentor to W.E.B. Du Bois, also apprenticed with Louis Agassiz as a young man, and while James recognized Agassiz as a specialist in “humbug” retained his affections for his mentor throughout his life. Even in the case of enlightened figures like James, or writers like Emerson and Whitman who contributed so much kindling to the emerging project of pragmatism, we might note, as David W. Noble argues in his masterful work Death of a Nation, that even the most progressive sons and daughters of the American establishment have retained a sense of “aesthetic authority,” a need to imagine the national landscape in Romantic and idealistic terms, that has served as a limit on their ability to come to terms with US history with, as Kenneth Burke might say, “maximum forensic complexity.” The point, here, is to avoid Manichaeism, not simply to jump from a negation to an affirmation, or vice versa.

The history of capitalism, The New York Times tells us, is back on the table in US history departments. What interests me in projects such as this is the possibility of getting a more detailed picture of the intersection of changing intellectual currents, to consider the changing meaning and function of big-ticket notions like “culture,” “value,” “authorship,” and “work” in order to arrive at a more fine-grained account of the history of capitalism. John Commons noted in his Legal Foundations of Capitalism that the Progressive Era-Supreme Court occupied the “unique position of the first authoritative faculty of political economy in the world’s history.” Thus, Commons urged, historians of US capitalism should attend closely to the Court’s “theory of property, liberty, and value.” “For it is mainly upon that theory,” Commons concluded, “that modern business is conducted.” In its capacity as the world’s “first authoritative faculty of political economy in the world’s history,” at a given moment in time, the Court chose to attend closely to the unauthorized reproduction of some circus posters. In the final analysis, that’s pretty interesting.

[1] Daniel J. Czitrom, Media and the American Mind: From Morse to McLuhan (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982).

[2] Jacques Rancière, “Politics and Aesthetics: An Interview with Peter Hallward,” Angelaki, Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, Volume 8, Number 2, August 2003.

[3] Jacques Rancière, “Thinking between disciplines: an aesthetics of knowledge” (translated by Jon Roffe). Parrhesia Number 1, 2006.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Kurt,

Although I haven’t been an active commenter on your series, I’ve been following. I really need to devote some time to post #2; I need a better understanding of Livingston’s views of pragmatism especially. And I was intrigued to see (if not fully convinced) the Peirce-ian connections you made in post #3.

This is not *the* thrust of your post, but I want to challenge you a bit on your interpretation of Arnold. As I’ve written elsewhere, there’s a neglected strain of Arnold’s thought that can be interpreted as in favor of cultural democratization and hardcore critical thinking. I cover this in the article linked above (pp. 403-407), but he promoted critical thinking for the newspaper reading classes as much as he defended high culture from barbarism. Arnold sought to work against flabby middle and upper-class thinking by promoting critical thinking that subverted ideology and imparted some degree of intellectual independence. In sum, the Czitrom reading is one-sided in favor of Arnold’s elitism (which of course does exist), and that one-sidedness has been perpetuated in subsequent literature (e.g. Levine, J.S Rubin).

My revisionism rests on (a) a close rereading of Arnold’s own *Culture and Anarchy*; (b) a closer look at Arnold’s contemporaries and British and American descendants (pp. 407-413); and (c) the work of other scholars (past and recent)—P.J. Keating, Samuel Lipman, and most of all, Linda Ray Pratt (esp. her *Matthew Arnold Revisited*, 2000). Janice Radway has acknowledged the importance of Pratt in *A Feeling for Books* (1997), and Jonathan Rose has acknowledged this “other Arnold” in his important work, *The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes* (2001). – TL

Thanks very much for this comment, Tim. I look forward to checking out these sources.

It’s an admittedly small part of this post and your series, but I felt obligated to point it out. My article summarizes all of this in a brief space, but Pratt’s book is the best extended, and therefore more nuanced, version.

It would be good, because Arnold came up in the previous discussion with Nils Gilman, to have a more Arnold-focused discussion here at some point. I think that Raymond Williams’ Arnold is still worth defending, even if, as with the case of Hofstadter’s “paranoid style” analysis, every application of it to other cases seems to miss the nuances.

I wish now that I hadn’t left out a section on Holmes’s debts to Ruskin, whom he names as an intellectual inspiration in Bleistein. Many lefties thought of Ruskin as “their” guy until Said’s work on orientalism revealed Ruskin’s bigotry. (In fact, Edmund Burke was way better on colonialism than most of the craft socialists or quasi-socialists)Then, looking back on even the “good” Ruskin, like the Fors Clavigera, we see much of the same classism that gets Arnold such a bad reputation. Even William Morris sometimes sounds like Arnold. So I think the question is bigger than crude high/low politics, and much more infused with other, usually ignored, value distinctions. Would you be interested in a “rethinking Arnold” roundtable of some sort?

Maybe. I’m a bit preoccupied with late 20th century topics (as evident from my recent posts). But I’d be, at the very least, an active commenter on a roundtable of that sort.

NB: Thought I would note here a concordance I discovered today between a quote I used above to illustrate the consensus view of new media in the late 19th century (Alfred Berlyn’s “The restless rush of present day life, its constant distractions, its perpetual movement, its ubiquitous newspapers, with their ever shifting kaleidoscope of events and interests”) and a passage from Victor Burgin’s The Remembered Film I was reading today: “What we may call the ‘cinematic heterotopia’ is constituted across the variously virtual spaces in which we encounter displaced pieces of films: the Internet, the media and so on, but also the psychical space of a spectating subject that Baudelaire

first identified as ‘a kaleidoscope equipped with consciousness'”). Compare with Peirce and James on flux, consciousness, and duration.