The single greatest day in the history of American film criticism is August 14, 1967–the day that Bosley Crowther slammed Bonnie and Clyde in the New York Times. You laugh! That day film criticism became a full-intellectual-contact sport. Crowther was nearly crucified in letters he received from outraged readers. The “younger generation,” it appeared, did not share Crowther’s standards for movie violence nor his distaste for anti-heroes. Crowther’s colleagues excoriated him in print–Pauline Kael famously began her unusually long review of the film, “How do you make a good movie in this country without being jumped on?” Kael’s influence rose dramatically, so much so that her friend Joe Morgenstern changed his review in Newsweek from negative to positive. The upshot of the “Crowther Affair” was that the most influential movie critic in the country who wrote for the most respected newspaper in America’s single largest movie market had been taken down. The decade that followed this moment witnessed a tremendous outpouring of high-level critical debate about movies amidst one of the greatest periods of filmmaking in American history.

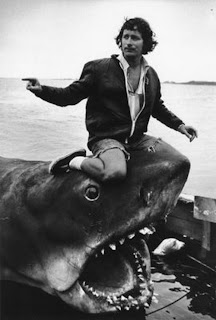

And then Steven Spielberg made Jaws.

Based on a best-selling novel by Peter Benchley, Jaws hit theaters in the summer of 1975 behind an advertising blitz that culminated in an opening weekend in over 400 theaters. While such an opening was not totally unprecedented, this single movie has often been regarded as the one that changed an era. As perhaps the first true blockbuster it recouped production costs in a few weeks and, just as important, it proved that film critics–with their ability to shape popular opinion–were growing irrelevant. The tradition of releasing a movie in New York and Los Angeles to build some buzz before sending the film across the nation, faded in the glow of Universal’s success with Jaws. Basking in that glow was 26-year old Steven Spielberg.

I am writing a long essay on Spielberg and film critics for a volume on the director that will include something on the order of twenty separate essays. In short, academics find Hollywood’s most successful director…interesting. This is so because, without a doubt, Spielberg is not only the most financially successful filmmaker in American history but also widely regarded as a very good filmmaker–not the greatest or the most innovative, but still a filmmaker that many talented people want to work with. And while not impervious to critiques from film critics, Spielberg is a very good storyteller and excellent technical filmmaker. In short, critics often don’t have much to complain about.

We have confirmation of that last point with the overwhelmingly positive critical reception of his latest film Lincoln. Generally Spielberg’s movies appeal to two sides of the critical community in the United States–he makes both great action/adventure movies and thoughtful period pieces. When critics sit down to write their review, it is no wonder that they thank the Hollywood gods that every so often Steven Spielberg makes a film that breaks up the schlock that comprises the vast majority of what they must watch.

And yet, there has been a chorus of discordant voices regarding Lincoln and the choices Spielberg and his team made when creating the film’s narrative. Ben Alpers has provided a great portal into the debate sparked by Lincoln. We know that other Spielberg films–The Color Purple, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, Amistad–have likewise caused flare-ups over choices of whom to focus on. Of course, when Spielberg focuses his lens on an event or historical actor, the effect is substantial and significant. As America’s most successful filmmaker, he generates a narrative that exists far beyond those in his films.

So what we often get with a Spielberg film is a general chorus of praise from film critics and a chorus of complaints from scholars. The critics know that their voices cannot do much to affect the Spielberg aura–and frankly most have no reason to try. Critics can write for public consumption of the film and for posterity, for people like me who attempt to take stock of what Spielberg has meant over the years to American film history.

For scholars of various stripes, though, Spielberg films create occasions of often intense and revealing debates. Over the past two weeks, I have thought more about the role of different historical forces, actors, and events in the fall of slavery than I would have if Spielberg’s movie hadn’t appeared. As a historian of the United States, I’ve profited a great deal from reading Eric Foner and James McPherson, David Goldfield and Dorris Kearns Goodwin, Ira Berlin and David Herbert Donald–but outside seminars in graduate school over a decade ago, I haven’t been engaged with texts on this subject like I have after reading Corey Robin, Ira Chernus, Aaron Bady, Tim Lacy, etc. on the film.

All this discussion reminds me of how I have pined to be part of the era in which Bonnie and Clyde entered the American debate over movies and culture. Except this time, rather than an establishment critic thundering on about the historical inaccuracy of a film and his critics screaming to shift his focus to the world revealed by that film, I read scholars thundering about the historical inaccuracy of Lincoln and their critics screaming that they, in effect, don’t want their world intruding on the one in the film. The debate sparked yet again by another Spielberg epic has been about the way we should remember the past as a people who use that past. Bonnie and Clyde created a similar moment in film history–the point was to argue over what the film meant as a culture signpost; at that time, critics moderated the debate. In our time, the moderators have changed, they are not film critics, but those of us engaged in a vigorous debate over how to represent our collective past.

It seems to me that the gold standard for sparking that kind of debate is Oliver Stone’s JFK. I teach the film every semester I teach a course on historiography. What better way to talk about and demonstrate the use of historical sources and argument than to witness one of the most manipulative and wrongheaded exercises in the historical method. Stone’s film is an utterly brilliant piece of filmmaking–if you want a good contemporary comparison to D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, JFK stands ready. While movies don’t “write history with lightening” (no matter what old Woodrow Wilson claimed), they do fire debates about how people can generate a broad, popular debate about our collective memory and the problems left unsettled. Robert Rosenstone argued: “If it is part of the burden of the historical work to make us rethink how we got to where we are and to make us question values that we and our leaders live by, then whatever its flaws, JFK has to be among the most important works of American history ever to appear on screen.”*

Indeed, for all it’s faults, Lincoln poses a moment to debate whether this nation, or any nation, ever truly had a “new birth of freedom.” And while we debate that claim, we should pause to affirm that our movies of the people, for the people, and by the people will not perish from vigorous critical–and scholarly–debate.

* Quoted in Robert Brent Toplin’s excellent treatment of debates over film and history, Reel History: In Defense of Hollywood (University of Kansas Press, 2002), p. 107.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I often think about the limitations of film when I see a movie like JFK, Amistad, or Lincoln. While they claim to be based on books they cannot capture in 2 hours what a well researched and written book delivers in 400 pages. There have been some good films that were made from short stories and I think that is because a short story is just about the right length. But trying to turn the work of a handful of historians into a feature film is an extraordinary challenge. As a result, details get left out, characters are altered or merged and those of us who take the time to do research and read books get bent out of shape over what is missing (everything from ignoring historical agency in Lincoln to altering chronology for no apparent reason in the John Adams mini-series).

Looking at films as representatives of their moment in time, as the artifacts of the generation in which they are created, is a more fulfilling intellectual exercise than poking holes in the narrative which can never truly seek to get the story right.

In the Chronicle Review, Kate Masur make similar points. It is interesting to see which phase we have now entered with this debate over Lincoln the movie.

Here is the link: http://chronicle.com/blogs/conversation/2012/11/30/a-filmmakers-imagination-and-a-historians/

Is “1941” a “great action/adventure” movie or a “thoughtful period” piece?

Gee whiz, good point.

My favorite Spielberg “period piece” is Minority Report. I’m probably in the “minority” here, but I think it’s a nearly perfect film given its intentions. I like to show the car factory scenes in class as an example of “technological unemployment”–for someone who’s livelihood now depends on the liveliness of Detroit, scary images indeed.

As I’ve pondered my own questions about the film, as well as the issues raised by Ray above (in addition to Robin, Bady, and Alpers), this review seems striking for how it goes towards Ray’s final point. I like how Zelikow situates the film as we would any addition to the historiography of a subject. If the film were a book, we would analyze its sources, check whether acknowledged and made use of the secondary literature, and, finally, most importantly added a new perspective in relation to those primary and secondary sources. Zelikow does this (despite the fact that the film doesn’t offer a full-fledged bibliography), and finds that Spielberg’s makes a novel contribution—and it’s entertaining to boot. I guess the overall point is that we need not always treat film SO differently. – TL