I read something very exciting this week, the introduction of Erin Chapman’s 2012 Prove It On Me: New Negroes, Sex, and Popular Culture in the 1920s. She argues many of the things I was searching to find here and here. I took four pages of notes on the introduction, and would love to share the quotes I so ardently took down, but in fairness to her and you, I’ll just share a couple. But I urge you to go read her work if you are interested in the politics of respectability, the way popular culture influences society, the New Negro era, or the limits imposed on feminism.

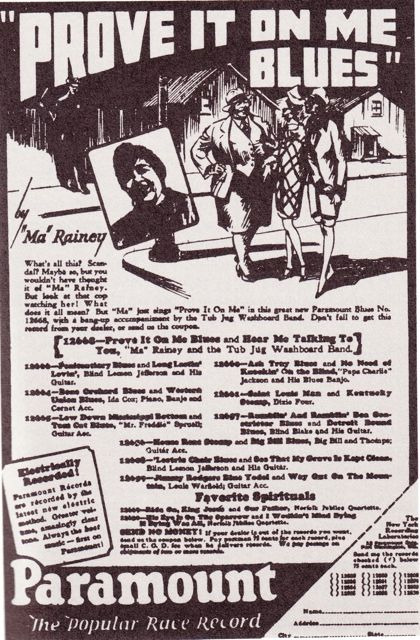

“Prove it on me” is a quote from a Ma Rainey song, which flirts with the audience and dares them to prove she’s done anything wrong. She “knows she is not completely free, but she acts independently anyway. … In the face of social and moral condemnation, this New Negro woman determined to shape her own identity and fate.” (3) But while she and other New Negro women insisted “on her right to enjoy, as sociologist E. Franklin Frazier lamented, the era’s ‘larger freedom of women,'” at the same time, “the question remained whether women, especially African American women, really had any more social, political, or economic power than they had had before.” The spectacle of freedom, rather than its reality “overshadowed the ongoing political suppression and exclusion of most black women’s voices. Instead of representing liberation, the prevalence of such spectacle indicated society’s use of black women’s bodies, images, and subjectivities to ‘prove’ –establish, test, assert, flout–the countless quandaries in gender roles, sexuality, and morality presented by the modern era and its new race politics.” (4)

Chapman captures the tension I mentioned in my first post on the politics of respectability, though she frames in terms of the New Negro debate over the meaning of art. Perhaps that was my mistake in the first post–not recognizing the transition between the politics of respectability and New Negro Modernism. After reading Chapman’s introduction, I can see how much the women I study straddle that line, sometimes evoking the one and sometimes evoking the other.

“Although modern African Americans determined to shape their own destinies, both in personal and political terms, and to take leading roles in the newly configured discursive debate over black humanity and worth, there was little agreement about the best means of accomplishing these aspirations. Thus, New Negroes were divided into two major camps. There were those who sought to modernize and professionalize established ideologies of racial advancement, solidarity, and uplift through a New Negro progressivism…. Others.. questioned, if not the very idea of racial solidarity itself, then at least the obligation of racial allegiance and respectability, and instead touted a radical individualism and independence from all but the most personal allegiances to ‘art’ or ‘self’ or some other self-generated ideal.” (10)

Chapman moves from the sex-race marketplace to the intrarace dialogue about the proper role of women and sexual morality. She argues that while “class-biased” uplift ideology of the National Association of Colored Women dominated what she calls the Reconstruction generation, a masculine-impulse dominated the New Negro era (12). The New Negroes “accentuated the manhood rights of the black male worker as a tenet of racial advancement” (11). Their politics led to an emphasis on what Chapman defines as “race motherhood,” which was not the heir of Reconstruction era feminism, “but a discourse confining black women’s subjectivity, identity, and activity to others’ support and use.” (13)

Chapman’s thesis represents a direct challenge to me: “As the great migration and converging economic and technological changes precipitated the formation of the sex-race marketplace that would shape the course of twentieth-century race politics and racialized popular culture, so too did the modern racial discourse motivate the development of an intra-racial discourse of race motherhood. Together, they rendered black women largely invisible, their subjectivity flat and inhuman, for the greater part of that century.” (14)

My work is all about New Negro women who updated uplift ideology for a modern world. I argue these women were not invisible in their Harlem society nor outside of it, to YWCA women, Pan-African leaders, the League of Nations and others. Chapman very explicitly says that her work is not about the women themselves or their “quotidian experiences,” but rather about the “social forces shaping” “the meanings dominant society, New Negro politics, and black women themselves made and attempted to make out of black women’s subjectivities.” (15)

Despite our different pursuits and methodologies, Chapman’s work is going to be very helpful to me as I attempt to understand the lived experience and inhabited ideas of four black New Negro women who traveled internationally because she defines the social forces constraining these women and against which they struggled. Can’t wait to read the rest of the book!

0