Editor's Note

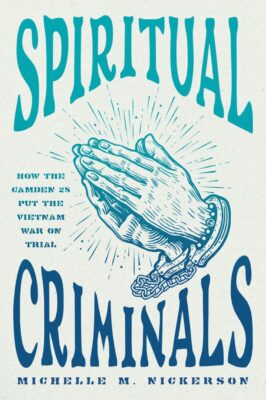

Post #11 in an ongoing series related to Michelle Nickerson’s Spiritual Criminals. This is the final entry.

Michelle Nickerson, *Spiritual Criminals: How the Camden 28 Put the Vietnam War on Trial* (University of Chicago Press, 2024)

Thus far in this series I have not articulated any critique of Michelle Nickerson’s Spiritual Criminals. One reason why is that these explorations were never meant to be a book review, much less a critical review. I felt no obligation, hence, to hold to a critical approach. My point with the posts was to highlight the book’s intellectually generative nature. For me, for instance, it enabled a rethinking of a period of Catholic activism that I had left personally unexplored due. Spiritual Criminals caused me to investigate my prior personal mindset which I laid out in the first entry of this series.

I felt, in part, that critique could take a backseat because Spiritual Criminals is a groundbreaking academic exploration of Catholic Leftism in the 1960s and early 1970s. There appears to be no clear academic model for this book in post-war American religious historiography. I will gladly accept correction on this point in the comments, but this appears to be sui generis work.

Also, this book is very well written. It is brief without leaving the reader feeling like the story is incomplete. It is jargon free. It is approachable and easy to read.

Today, however, I will risk some minor criticisms—or rather express my wishes for more elaboration and exploration. I have only four points to make.

First, I desired two reader aids: a timeline of all raids and a trial timeline. On the first, because Nickerson generates interest in other raids along the way the reader can be left, at times, trying to place the build up to the Camden-28 action in the context of a prior string of draft board raids. I found myself, for instance, regularly referring back to passages where I had marked the names of past actions. Nickerson’s good work makes one desire the full chronology of all raids in one easy reference spot. On the second—and this is a minor request—I wanted a handy place to see when the trial actions began, when particular witnesses appeared, etc.

An undated photo of Woodstock Theological Seminary. Found at this webpage: https://www.patheos.com/blogs/mcnamarasblog/2009/09/jesuit-seminary-opens-1869.html

Second, as a person with a strong interest in the history of higher education, I wished for a bit more context and detail on the collegiate experiences of various Camden-28 actors. Nickerson touches on the ideas and activities of Jesuit novitiates at Woodstock Theological Seminary in New York City (pp. 9, 59). She notes their off-campus housing, which enabled new kinds of connections between students, their families, and activists. Otherwise, on the Camden-28, some of them attended a little college while engaging in activism. Some of them dropped out temporarily. Some of them had, I think, completed their degrees. I wonder what they studied, where they studied it, and with whom? If they dropped out, why? If they finished, why? In sum, I wanted to know more about the kinds of education in the 1960s that enabled transformation in the lives of its learners. Which Catholic institutions produced the most activists? As you can see, I have lots of questions.

Third, I wondered about the “soundscape” of the Catholic portion of the anti-Vietnam War movement. Inspired here by Michael Kramer’s 2013 book, The Republic of Rock (reflections on it here, here, and here), I started thinking about how democracy and equality are fostered by a common musical base. The Catholic Left had a rhythm; an inspiring soundscape certainly existed. Nickerson teases us with it at certain points. She notes that draft-board-raider idealists “sang ‘We Shall Overcome’ and other spirituals,” and that “all sang from the political soundtrack of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Jimi Hendrix, and other folk and rock musicians” (pp. 7-8). At the Woodstock Seminary wedding of two activists (Anne Dunham and Frank Pommersheim) in 1971, Pete Seeger’s “To Everything There is a Season” was sung (p. 64). Music mattered to the Camden-28.

That said, which artists resonated the most with Camden-28 actors and other draft-board raiders? Were they more motivated by Baez, or Dylan, or Seeger? Or maybe the Staple Singers, Nina Simone, or Sam Cooke? Or the Beatles, James Brown, or the Rolling Stones? Who were the Camden-28 listening to in the days just before the break in? I think the soundscape of the Catholic Resistance may have affected their “structure of feeling”—to invoke the almost immortal 1954 words of Raymond Williams.[1] Music had to have helped in the emergence of new thoughts about leftism, resistance, politics, and theology. At a minimum, music certainly enables community and solidarity.

That said, which artists resonated the most with Camden-28 actors and other draft-board raiders? Were they more motivated by Baez, or Dylan, or Seeger? Or maybe the Staple Singers, Nina Simone, or Sam Cooke? Or the Beatles, James Brown, or the Rolling Stones? Who were the Camden-28 listening to in the days just before the break in? I think the soundscape of the Catholic Resistance may have affected their “structure of feeling”—to invoke the almost immortal 1954 words of Raymond Williams.[1] Music had to have helped in the emergence of new thoughts about leftism, resistance, politics, and theology. At a minimum, music certainly enables community and solidarity.

Lastly, I wondered about anti-Catholicism in relation to larger public views of the Catholic actions. We know that anti-Catholicism had lessened during the Cold War, but we also know that it did not entirely disappear, especially in rural and Midwestern areas. Were critics of Catholic-based draft-board raids more against the action or the actors? How did anti-Catholicism function on The Left? Was there an element in the FBI? Did JFK’s election sweep away anti-Catholic sentiment in mid-to-late 1960s politics?

My middle two wishes—on higher ed and the soundscapes—are probably worthy of independent articles, or even separate books. Both offer chances to add to the historiography to which Nickerson has now contributed greatly.

Despite my questions and wishes, there is so much to praise in Spiritual Criminals. It deserves plaudits for its readability, as an addition to the historiography on both 1960s Catholicism and the antiwar Left, for its legal history (e.g., jury nullification), for its long look at the FBI and Hoover, for its deep contextualization of the draft board raiders and the Camden-28, and for its humane reflection on the personal aftermath of the Catholic Left’s activities. No Catholic who cares about politics and activism should neglect to add Spiritual Criminals to their bookshelves. And yes, I still think this book would make a great movie!

——————————————–

Notes

[1] First articulated in a 1954 Williams work, “Preface to Film.” He elaborated and expanded on it in The Long Revolution (1961) and Marxism and Literature (1977).

0