Editor's Note

Post #9 in an ongoing series related to Michelle Nickerson’s Spiritual Criminals.

While all anti-Vietnam War activities eventually put a spotlight on reactions by law enforcement, in reading Michelle Nickerson’s Spiritual Criminals I was surprised at the extent the Camden 28 action involved the Federal Bureau of Investigation and its Counter-Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO).

Historians who work on the 1960s already know about COINTELPRO and how it targeted higher-profile antiwar activists in the New Left. Because I have taught on this decade I knew that COINTELPRO had hunted down The Weathermen and pursued The Weather Underground. Until reading Nickerson’s book, however, I had not absorbed the number and breadth of draft board raids and actions and the potential involvement of federal investigators. Nickerson’s contextualization of the FBI side of the Camden 28 story—to set the stage for the trial in early 1973—helped me to more fully understand the extent of COINTELPRO’s illegal activities.

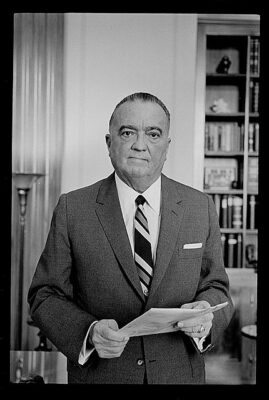

Edgar J. Hoover, Sept. 28, 1961, Photographed by Marion S. Trikosko. Courtesy of LOC; Accessed 12/18/24.

Backing up, any exploration of the FBI and COINTELPRO means meditating on J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover is introduced in chapter five as having “targeted the Camden draft board raiders because some of them had stolen, and started leaking, files that revealed secret and illegal FBI activities” (pp. 98, 100). Hoover worried that this information was reaching journalists. It would demonstrate “the truth” about the extent of “systematic political harassment conducted by the FBI” (p. 100). Hoover’s reputation as a patriot and loyal government official was on the line—and the Catholic Left and its ‘spiritual criminals” might be behind his potential undoing.

Nickerson shows how the Catholic Left absolutely helped on that front. As she puts it, “instead of facing the music when the truth [about Hoover’s illegal activities] came out in April 1971, [he] responded to the exposure by doubling down” on those who were exposing him (p. 100). Hoover’s troubles began with a raid on an FBI satellite office in Media, Pennsylvania in March of that year. In relation to the Camden 28, the FBI was convinced that the same Media raiders were involved in both actions.

The Media-PA raid, however, was connected in a fashion that was less than direct. There were two common actors, but the Media action was organized by the 44-year-old pacifist, William Davidon. At the time he was a Haverford College mathematics professor (p. 100). Davidon’s entry into the Catholic Left was the Berrigan Brothers. Nickerson said he saw them “as a stabilizing, moral, and effective flank of the antiwar movement”—“grounded and disciplined” (p. 101). Davidon, moreover, had become concerned about FBI informants embedded in peace organizations. This meant that he put a premium on secrecy.

The names and number (eight) of Media raiders was kept secret for decades.[1] In addition to Davidon, the raiders included John C. Raines and his spouse, Bonnie Raider, Keith Forsyth, Bob Williamson, and Judi Feingold (Forsyth and Williamson were the common elements). Two other Media raiders remained anonymous for years. In 2021, Ralph Daniel came forward and then, the last, Sara Shumer, in 2024. Shumer was also a Haverford professor. Neither Daniel nor Shumer are mentioned in Spiritual Criminals. The raiders eventually took a collective name: “Citizens’ Commission for the Exposure of the FBI” (p. 101, 103).[2]

The documents recovered from the Media (PA) office proved damning and invaluable regarding the Hoover-approved clandestine FBI work. The action itself was stunning. Nickerson dramatizes the situation quite well, noting the timing and larger cultural circumstances (occurred during the Ali-Frazier “Fight of the Century”). After reading, organizing, and copying their stolen documents, the raiders mailed packages of relevant materials to newspapers and legislators (p. 103). It was the first time that FBI materials had been successfully stolen since the 1949 “Coplon Case” regarding the accused spy Judith Coplon.[3] Unfortunately, some who received the Media office information—including Senators George McGovern and Parren Mitchell, as well as the LA Times—turned the information over to the FBI rather than leaking it (p. 103). The entities who released the information, however, changed the course of the FBI and the nation.

The Media-PA raiders discovered a number of interesting, unethical, and illegal secrets. First, they found an unauthorized “Security Index…of alleged subversives started by…Hoover in 1939.” By 1971, that list consisted of approximately 26,000 names of those “who…should be arrested in the case of a national emergency” (p. 103).[4] Moreover, the FBI had been engaging in illegal wiretaps of phones. They had also conducted illegal raids on homes to collect damaging information on those Hoover believe to be “state enemies” (p. 103),

These actions, and the resultant information collected, were commonly used to blackmail suspected subversives and criminals, or to wield as a political weapons. These tactics were first used “against suspected mobsters, terrorists, and communists” but were then turned on “activists in the civil rights, free speech, antiwar, and other movements” (p. 103-04). Several examples exist in scholarship of the Civil Rights Movement. Nickerson relays, for instance, the well-known fact that the FBI had monitored Martin Luther King, Jr. In addition, scholars of Malcolm X’s story know that he too was harassed by the FBI. The Media raiders “also revealed that the FBI had furnished the Chicago Police Department with a diagram of the apartment building belonging to Black Panther Fred Hampton” (p. 104). This information led to the killing of Hampton in his own bed.

In the documents collected the Media-PA raiders ran across the unknown term “COINTELPRO.” It would “take a few more years of investigation by government officials and journalists” to identify the meaning of the acronym (p. 104). The COINTELPRO program was, in essence, the means by which the FBI’s counter-subversive activities had taken place. It had begun, Nickerson writes, after a 1950s Supreme Court decision.

Whole U.S. Supreme Court Building from front and center. Circa 1920s-1950s. Photo by Theodor Horydczak

That particular SCOTUS decision is not named in the text, but likely references Yates v. United States. The Yates decision sided with Communist Party USA members on free speech issues—increasing free speech rights such that the Smith Act become extremely difficult to enforce. It was decided with three other cases (Service v. Dulles, Sweezy v. New Hampshire, Watkins v. United States) on the so-called “Red Monday” of June 17, 1957.[5] The Yates decision is fascinating. For the purposes of this reflection, it is sufficient to know that it helped, ironically, to incite Hoover into greater anticipatory counter-subversive actions. Nickerson reminds us that Hoover felt compelled to “quash efforts before they were even started” by those he believed to be subversives (p. 104).

The Media-PA files were released in April 1971. A 4/6/71 story by Betty Medsger first revealed COINTELPRO to the public. This caused Hoover to order the cessation of all FBI internal communications about the program (pp. 104-105). The attempted coverup, however, did not prevent damage to the reputation of Hoover and the FBI. Nickerson documents that negative press subsequently occurred in Time, Life, and the New York Times. The revelations caused Hoover to do what he did best: launch a deep investigation of the Media (PA) raid and its related document release. That project was called “MEDBURG”—short for Media burglary. Meanwhile, COINTELPRO continued under different auspices, as specifically and individually directed by Hoover (pp. 105-106).

How does all of this relate to the Camden-28 and its raid? Again, Hoover believed that the exact same actors involved in the Camden action had performed the Media-PA raid. He mistakenly thought that they were connected. This suspicion drove the intensity of the Camden-28 monitoring and investigation. Nickerson relays that Hoover assigned the famous Roy K. Moore—of Mississippi Burning fame (the 1988 film)—to the Camden case. Moore was given extensive resources, including a squad of 100 agents. They were focused was John Peter Grady instead of William Davidon (pp. 106-107). Hoover and Moore kept the spotlight on Grady through the Camden-28 action, thinking it would allow them to uncover the details of the Media-PA raid. They knew that 77 of 1,013 total Media-PA items had appeared in the news. Nickerson states: “The FBI poured resources into overtime hours, technology, informant expenses, and other costs associated with the MEDBURG investigation” (p. 109). Those expenses, which translated to the Camden-28 action, would eventually include $5000 (in cash) that went to their specific Camden-28 mole (p. 112). It was all for naught. They were wrong.

Michelle Nickerson, *Spiritual Criminals: How the Camden 28 Put the Vietnam War on Trial* (University of Chicago Press, 2024)

Hoover then drops out of Nickerson’s story for a long stretch. She picks him, and the FBI, up again in the aftermath of the Camden-28 trial. She argues that Hoover’s failure with MEDBURG and the Camdem-28 allowed “the outflow of information about the government’s illegal activities”—damaging the reputation of the Bureau and Hoover (p. 191). Two raiders common to both, Bob Williamson and Keith Forsyth, were never identified by the FBI. The solidarity among Camden-28 raiders frustrated the Bureau’s efforts (p. 191).

The story of COINTELPRO emerged as the 1970s progressed. Hoover himself died May of 1972. Nickerson reminds us that, after additional reports of CIA malfeasance and its own files on antiwar activists, the Senate established, in early 1975, the “Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities.” This was shortened to “The Church Committee,” after its chair, the Idaho Democrat Frank Church (p. 192). Hoover could not be brought to justice, but the work of the Church Committee did result in the regulation of spy activities. Its work helped enable passage of the 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. That law established a formal system for “government officials…[to] obtain a court-authorized warrant to conduct wiretaps and other surveillance for foreign intelligence information” (p. 192).

The Catholic Left, then, and its Camden-28 actors in particular, helped in the overall effort tear down illegal systems of domestic surveillance. They brought discredit to Hoover and the FBI. Nickerson succeeds in connecting the Catholic Left to this larger, more important story in US history.

——————————————–

Notes

[1] The authoritative book on the Media, PA raid is Betty Medsger’s 2014 book, The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI (New York: Oxford University Press).

[2] Matthias Gafni, “‘Something Had to Be Done’: 50 Years after an FBI Office Burglary, a San Rafael Man Reveals His Role,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 7, 2021, https://www.sfchronicle.com/local/article/50-years-after-the-famous-FBI-office-burglary-16001070.php; Omari Daniels, “Ed Helms’s Podcast Explores a Washington Post Scoop That Rocked America,” Washington Post, June 26, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2024/06/26/ed-helms-podcast-snafu-fbi/.

[3] Nickerson references Beverly Gage’s G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (New York: Viking, 2022) as authoritative on the Coplon Case.

[4] See also John Hall, “The FBI’s Secret List of ‘Dangerous’ Americans was…,” San Francisco Examiner, May 23, 1976, pp. 18-19. Available at this link. Accessed 12/2/2024.

[5] The text of Spiritual Criminals says 1956 for the creation of COINTELPRO, but the decision was rendered in 1957. Perhaps Hoover began COINTELPRO in anticipation of it. For more on the Yates decision and Red Monday, see: Elizabeth J. Elias, “Red Monday and its Aftermath: The Supreme Court’s Flip-flop Over Communism in the Late 1950s,” Hofstra Law Review, Vol. 43: Iss. 1, Article 16 (2014), available at this link, accessed 12/2/2024.

0