The Book

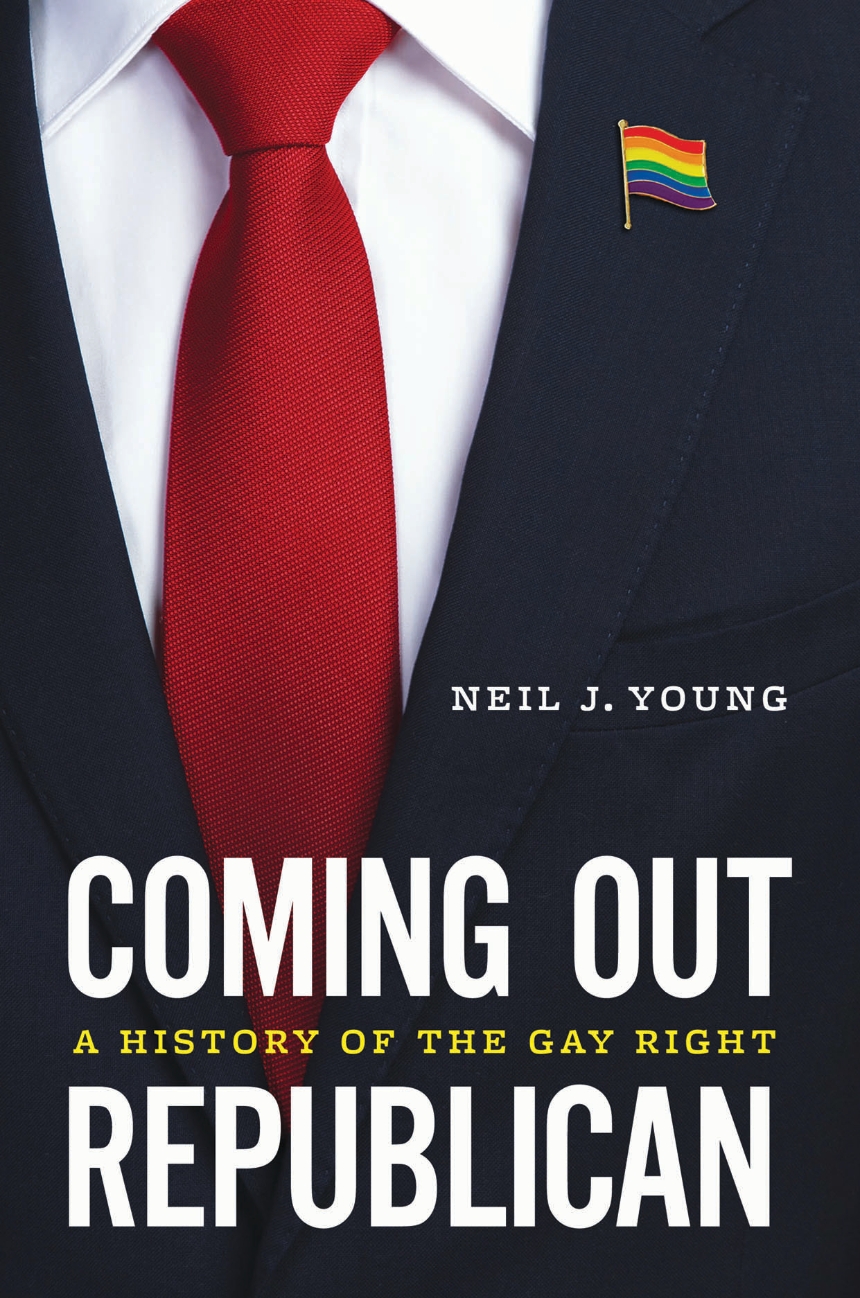

Coming Out Republican: A History of the Gay Right

The Author(s)

Neil J. Young

As Republican politicians such as Florida Governor Ron DeSantis support and pass legislation that curtails LGBTQ+ rights it is worth asking: are there any gay people in the Republican Party or on the Right in the U.S.? Neil J. Young’s Coming Out Republican traces the fascinating history of conservative and libertarian gay figures in United States history who shaped the modern Republican Party, whether through their individual and intellectual contributions, or through Republican advocacy organizations such as the Log Cabin Republicans. Beginning with Dorr Legg’s individualistic Republicanism and problems with the communist-leaning leadership of Los Angeles’s Mattachine Society in the 1950s, Young first illustrates how both Republicans and Democrats were merely ambivalent or even antagonistic to the gay rights movement. He shows how gay Republicans gravitated towards ideals of individualism, anti-Communism, and freedom from government interference to articulate a conservative politics that incorporated their sexuality.

From that vantage point, Young goes on to show how later gay Republicans — and he uses the word gay pointedly, for the vast majority of the people in this book are gay white men — resisted framing their sexuality as the defining identity of their lives and politics, even as it defined the political action groups, laws, and suits that they rallied around. From the 1970s on, Young’s gay Republicans began a pattern of disavowing “identity politics” as they termed them, and distancing themselves from other minority groups in favor of political connections that emphasize their shared whiteness, maleness, and affluence. Especially in the period of the 1970s and 80s, the main actors in Young’s history concealed their sexual proclivities, sometimes going as far as to rail against the “decline of family values” alongside religious conservatives while covertly visiting bathhouses, gay bars, and other places frequented by gay men. While some on the gay right sought to push back against what they saw as the slow takeover of the Republican party, Young shows that other gay conservative politicians and intellectuals saw the religious conservative bloc as a voting base to be energized and used for their pro-business Cold War political agenda.

Young’s well-researched and well-written history helps us to answer the question of how conservative gay men sought political representation in the second half of the twentieth and early twenty-first century. Importantly, it also upsets the notion that gay rights have always been the sole province of the Democratic Party in U.S. politics. As Young convincingly shows, both parties largely eschewed supporting gay and lesbians for much of the twentieth century, and President Barack Obama, later celebrated for his progressive stance on the issue, did not espouse marriage equality during his first presidential campaign in 2008. Gay Republicans worked both behind the scenes and out in front to push their party to make life better for gay Americans from their point of view — through ideas such as individual liberties, strong national defense, and low taxes — using the language of conservatism to argue that gay Americans should be allowed to serve in the military, marry, and pursue economic security alongside their fellow citizens.

The final chapters of the book approach our current political moment as Young examines the Alt-Right and social media personalities such as Milo Yiannopoulos. By tracing Yiannopoulos’s rapid rise and fall within the online conservative sphere, Young shows how modern young conservatives see themselves simultaneously as accepting of gays and lesbians while also deploring feminism, political-correctness, and DEI initiatives that they see as unfairly burdening white men. Ultimately, Young’s important book is a history not only of the gay right but also a history of how whiteness, maleness, and affluence are powerful political and social identities which have influenced and continue to unite actors across the American right.

About the Reviewer

Hooper Schultz is an oral historian and PhD candidate in the History Department at UNC-Chapel Hill. He earned his MA in Southern Studies and MFA in Documentary Expressions at the University of Mississippi. His research interests include the queer South, gay liberation and lesbian-feminism, student activism, and queer oral history. His dissertation research focuses on the history of gay liberation era activism in college towns and on university campuses in the U.S. South.

0