Editor's Note

Post #8 in an ongoing series related to Michelle Nickerson’s Spiritual Criminals. Today’s entry is the second of two on the topic of feminism and the Camden 28.

The next time that feminism arises in the index of Spiritual Criminals is related to abortion and the aftermath of the Camden 28 trial (p. 189). In the penultimate and final chapters, Nickerson begins to take a broader view of everyone and every institution involved. She writes:

Michelle Nickerson, *Spiritual Criminals: How the Camden 28 Put the Vietnam War on Trial* (University of Chicago Press, 2024)

A split between feminists and the Catholic vanguard over reproductive rights blunted the impact of the Catholic Left. The pro-life mantra against abortion had taken root in Catholic peace politics before it became an expression of conservative antifeminism. …The ‘choose life’ shorthand for ‘stop abortion’ emerged as a universal humanitarian cry to respect all life in the 1960s. The Vatican had also denounced abortion and birth control in demands for the ‘sanctity of life’ since both became more available in the 1930s (p. 189).

Just as the Vietnam War provided grist for mill in terms of draft board feminist activism, it also activated deeper impulses in Catholic observers about “the American government’s disregard for human life in warfare” (p. 189). Politically left-leaning pro-life activists “wanted the movement to speak out against all attacks on human life, whether…directed against an unborn baby…a convicted criminal in an electric chair, or a civilian in a Vietnamese village.” Nickerson notes that “Daniel Berrigan wrote a blistering attack on abortion in the Christian magazine Sojourners” (p. 189).

The book concludes here that “the antiabortion movement…represented a fork in the road for Vietnam-era Catholic radicals” (p. 190). It would be a barrier to “former collaborators” in future work. One of the Camden 28 in particular, Cookie Ridolfi, noted that “she had no interest in fighting abortion” when queried by Daniel Berrigan (p. 190).

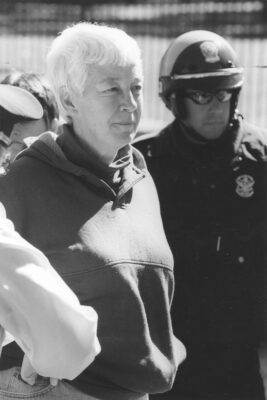

The comments of Elizabeth McAlister—spouse of Philip Berrigan and former nun—highlight why some former activists did not want to work for, or promote, the pro-life movement.

Elizabeth “Liz” McAlister in 2001. Courtesy of Wikipedia (accessed 11/22/24)

In a 1980 article for Sojourners magazine, she said:

I believe our culture is morally bankrupt…and I don’t think it right or just to put the burden of transforming our moral values as a people onto the shoulders of young women who are, in most respects, victims of those values—being women and thus objects; being poor and thus a burden; being members of a society where the military and leadership have gone mad, and being thus expendable (p. 190).

Later, in 1996, McAlister broached another key topic in another Sojourners article: women’s sexual desire. MacAlister wrote in defense of women’s those desires and acts. At that time, however, she could only promote those acts in the context of marriage and in view of parenthood. She even would say, in Nickerson’s words, that “sex outside of committed relationships…represent[ed] a form of violence” (p. 190). These reflections represent, for sure, some distance from her clandestine romance with Philip Berrigan in the late 1960s.

There is no way, of course, to divorce sexual expression from questions of feminism and activism. These activists were mere humans, after all.

Nickerson confronts these topics in chapter three, titled “One Big Catholic Movement Family.” Therein she meditates on “the erotics of activism” (p. 63). She notes that “sexual relationships abounded” in the communal living circumstances of the Catholic Left. There existed at the time “a sexual elixir in settings where people fell in love with each other’s political zeal.” The sexual revolution and radical action overlapped in a movement mentality. In a moment of disobedience and liberation, activists felt they had “the green light to act on their longings” (p. 63).

The reflections of Bill Ayers help, in the text, to underscore how these uninhibited relationships reified key inequalities. For instance, the consequences of sexual liaisons (i.e., pregnancy) affected female partners more than men in the movements. As one of Ayers’ friends bluntly noted: “Free love only meant that movement men could screw any woman they could get, free of emotional encumbrances.” The erotics of activism included, and gave cover for, “sexual exploitation” (p. 63).

The Catholic Left and the Camden 28 were not immune from this atmosphere. Nickerson notes, in a discussion that begins with changes around the Woodstock Theological Seminary after its move to Morningside Heights (NYC’s Upper West Side), that both “liturgical and lifestyle experimentation” that occurred there. This included relationships between seminarians and women. This, in turn, fed rel

This is John Peter Grady’s mugshot, taken from a mosaic of 20 mugshots published August 22, 1971, in newspapers around the country. It appears on page 99 of *Spiritual Criminals*, and comes from the *Camden Courier-Post*.

ationships with other communities of radical Catholics (p. 59).

These relationships produced both some happiness and some tragedy. On the former, apart from Philip Berrigan and Elizabeth McAlister, Camden 28 activist Anne Dunham met her future husband and fellow Camden 28 activist while preparing for that action. Radical Catholic Leftists, and former nun and priest, Sister Anne Walsh and Father Robert Cunnane, coupled as a result of their shared activism. Same with Mary Cain and Tony Scoblick (pp. 64-66). Happy coupling occurred among a number of activist individuals.

These kinds of intimate relations can also produce tragedy. In relation to Camden 28 participants, it was John Peter Grady, the action’s leader, who introduced complications. Grady’s relationships injected sexual tension and exploitation into the action. Grady was then married, the father of five children with his spouse, and, finally, an alcoholic. He was also non-monogamous—a player among his fellow women activists. Grady is known to have been sexually involved with several women (at least three) in, and around, the Camden 28 group (p. 70, 75).[1] Grady’s dishonesty and instability eventually put the entire action at risk when he decided to allow a new person, Bob Hardy, into the action in its last month or so of planning. That allowance was not based on his sexual exploits, but rather underscored his penchant for risk-taking.

The personal failings of Grady, as well as the politics of reproduction and sexual freedom, then, interfered with the solidarity of Camden 28 draft board action members. These issues splintered the group. They maintained some unity, however, in the short term due to a common enemy: the FBI. The trial of the Camden 28 enabled them to work for each other.

Feminism, then, when combined with the larger atmosphere of insubordination and sexual inhibition, proved both invigorating and troublesome for the Camden 28. It enabled the draft board action, but also introduced complexities that would drive members apart in the aftermath.

—————————————————–

Notes

[a] Anita Ricci, Cookie Ridolfi, Lianne Moccia, and Anne Walsh. Walsh was not a Camden 28 defendant. Nickerson returns to the relationships at others times in the narrative (pp. 91, 108, 110).

0