Editor's Note

Post #6 in an ongoing series related to Michelle Nickerson’s Spiritual Criminals.

Michelle Nickerson, *Spiritual Criminals: How the Camden 28 Put the Vietnam War on Trial* (University of Chicago Press, 2024)

In Spiritual Criminals, Michelle Nickerson relays an obvious but salient fact: the development of the Catholic Left in the 1960s “overlapped with the feminist movement as well as the civil rights movement” (p. 49). My prior posts in this series have touched more on the civil rights movement than feminism. In any discussion of Catholicism, however, some meditation on its historical (and present) patriarchal structure is unavoidable. One must reckon with how material, social, and theological structure of the institution is gender-based. In the context of this book, moreover, it must be applied to political and social activism in a context of conflict and radical change. The focus of today’s reflection is something of a backgrounder: masculinity. Next week I’ll continue with feminism.

As was the case in New Left student activism and the Black Power Movement, young women faced discrimination from men attached to traditional gender roles. Structures of masculinity prevented men from reflexively doing the dishes, child-rearing, cleaning, and emotional work. In Nickerson’s words, it was “a masculine activist culture that marginalized their female cohorts”—with men “stepping forward as the spokespeople while leaving the secretarial and housekeeping work to their sisters in the movement” (p. 50). Everyone in the various movements seemed complicit in “a system perpetuated by a socially implicit valorization of male strength, power, and wealth.” This system supported the military-industrial complex as much as any politician or president (p. 49). Of course that larger cultural, social, political, and religious power had a name: the patriarchy. We can also just call is sexism.

Despite the patriarchal norms (and pressures) of the period, one interesting fact about the Camden 28 is that 10 of its activists were women. I haven’t studied every draft board action, but it appears that the number and percentage of women involved might be the greatest among all the actions. Nickerson does not confirm this, so I will leave the fact-checking here to an industrious graduate student. I suspect that the Camden 28 action, being one of the last like it, benefited from the growing power of feminism in the 1960s.

The cover of Marian Mollin’s *Pacifism in Modern America: Egalitarianism and Protest*.

Put another way, masculinity and sexism and 1960s limited, or hampered, the power of the antiwar movement. In Catholic circles, “the Catholic model of manhood” affected the trajectory of draft board actions (p. 50). Here Nickerson invokes the work of historian Marian Mollin, especially her 2006 book Radical Pacifism in Modern America: Egalitarianism and Protest (Penn Press originally, now published by De Gruyter). Here’s how Mollin is discussed:

Catholic Leftists were referred to as a ‘brotherhood of scholars, students, and clergy’. The Berrigans…assumed the roles of modern prophet and apostle that the movement bestowed, mirroring attitudes of ‘its religious base, where priests were valued above all others and where women, by definition of their sex, were excluded from authority’. Mollin contrasts the Catholic way of peace with the Quaker egalitarianism that dominated American radicalism until that point (p. 50).

Catholic draft board raiders implicitly and explicitly invoked Catholic male authority to legitimize their actions. The demographics of the Camden 28 might put a dent in this, but it too was a masculine action dominated by male authority and female helpers.

To bolster the story around draft raider masculinity and its (literal) father figures, Nickerson builds a milieu. She invokes a 2012 essay by Robert Orsi wherein he discusses “clerical noir” from this period—a line of stories that valorized “hardboiled” priests who, in Nickerson’s words, “ventured into dangerous crime-ridden neighborhoods” to rescue the oppressed and abused (p. 50). The Berrigans are cited for their brashness and ostentatiousness with regard to raids. Dan Berrigan believed that these actions were crucibles for transitioning into manhood. A “male bravado” lifted male draft raid participants into “warriors for peace” instead of criminality (p. 50).

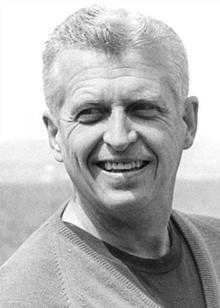

This is an undated picture of Philip Berrigan obtained from Wikipedia

Philip Berrigan seems to have developed a “pugnacious” white-guy coach persona that recalls a masculine intensity on the level (say, in college basketball) of Bob Knight, Bo Ryan, Tom Izzo, and others. Nickerson says that this particular Berrigan brother “simultaneously motivated and intimidated the activists in his midst” (p. 51). His forcefulness would isolate members; non-participation meant being “frozen out of his circle.” He admitted later to admonishing activists “about the war” and “their Christian duty” (p. 51). Philip Berrigan called himself “hard-nosed,” but today he would likely be labeled a bully. This is, of course, ironic in relation to nonviolent work in which he had immersed himself. Bully-like coaching is certainly not one of “four basic steps” invoked by Martin Luther King, Jr. in his famous explanation of direct action in “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (Aug. 1963, para 6).

Nickerson then discusses the looks and charisma of each Berrigan brother. Philip was commonly described as “handsome” or “strong.” His drive and energy were noted by others (p. 51). Daniel exuded a dark beat poet persona. Nickerson relays that he favored “black turtlenecks draped with a flashy medallion, sometimes wearing a beret and soul patch.” He was charming across many audiences. Sargent Shriver brought Dan Berrigan into contact with the Kennedy family. He “celebrated Mass for the family and visited them at their exclusive Hyannis Port [MA] compound” (p. 51). The Berrigan brothers were men of substance in Catholic world that celebrated male celebrity and leadership.

To be clear, the Camden 28 action did not directly involve the Berrigans. They merely informed the context of action, nonconformity, masculinity, and justified lawbreaking that would inspire the Camden 28. That said, Camden 28 action leader, John Peter Grady, represented a number of the problems that came with Catholic masculinity in the activist realm. More on Grady later, in another post.

Spiritual Criminals does an excellent job setting the scene for some of the problems that would follow in relation to the Camden 28 draft board raid. One of those problems involved its male leadership—their bravado, indulgences, and sexism. Catholic masculinity both contributed to, and subtracted from, the sustainability of a Catholic left after the draft board actions concluded. As usual, the patriarchal aspects of Catholicism presented problems for the flock and its relationship with activism in a democratic republic. Nickerson uses these meditations on masculinity to set up a larger point about how feminism informed the the Camden 28 action.

0