Editor's Note

This is Post #2 in the ongoing series on Michelle Nickerson’s Spiritual Criminals.

In the first full narrative chapter of Spiritual Criminals: How the Camden 28 Put the Vietnam War on Trial, Michelle Nickerson sets up the contextual train of teaching and ideas in the United States, Catholic and otherwise, that allowed the “Camden 28” to come into being. Her goal is to explain how a Catholic Left, or “Resistance,” could arise. Of course the Vietnam War sets a unique context, but Catholicism itself had a history in the United States that could explain political tendencies that fit the right, left, and center. One pivotal postwar figure for Catholics and politics was Cardinal Francis Spellman (1889-1967).

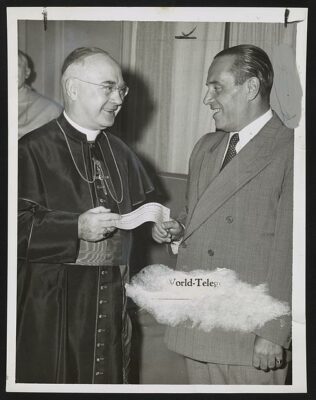

Photograph showing the president of the Columbian Citizen Committee, Generoso Pope, presenting a $3000 check for parochial schools to Cardinal Spellman. From the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2013646379/

I have been thinking about Cardinal Spellman since the early days of my graduate studies in history. I arrived at an interest in him, however, in roundabout fashion. One of my first-year papers, for the standard graduate historiography course, focused on the Seneca, Illinois-born “Dean of U.S. Catholic Historians,” John Tracy Ellis (1905-1992). Ellis’s name arose for me, indirectly, in the context of reading Peter Novick’s That Noble Dream (1988). Novick discussed prejudice in the profession against Jews and continued his reflections by meditating on anti-Catholic prejudices.[1] Ellis does not appear in Novick’s text, but the book pushed me to think about Catholic historians of all stripes. In conversation with my professor at the time (a former nun), Ellis was suggested as a paper topic. Writing that paper helped me see that Ellis covered a variety of topics in his works: James Cardinal Gibbons (in a two-volume magnum opus), Anglo-Papal relations, anti-Catholicism, Catholic intellectual life (qualities and problems), a survey on American Catholicism (1956/1969), and a 1983 memoir on Catholic Bishops.[2] The last contains some of Ellis’ thoughts on Spellman.

But who was Spellman? I learned more not only through Ellis, but also John McGreevy.[3] In the 1969 edition of American Catholicism, Ellis sets up his introduction of Spellman with a discussion of “civil religion” (p. 190). Ellis’ version of civil religion is something fed by the practices (and beliefs) of Catholics, Jews, and Protestants. It provides a nationalistic language of prophets, martyrs, sacred events, sacred places, symbols, and solemn rituals. He notes a downside: the employment of civil religion by political “rascals and mountebanks for selfish purposes” (p. 190). With Catholics, however, he notes their adoption of it as rooted in insecurities about the acceptance of Catholic immigrants and an “eagerness to ‘belong’”(p. 190). Catholic practitioners of civil religion included Archbishops John Carroll and John Huges, Cardinal James Gibbons, and, last but not least, Cardinal Spellman. Ellis calls Spellman its “most eloquent exponent.” That said, Spellman’s vision of civil religion also thoroughly corresponded with Stephen Decatur’s 1815 sentiment of “our country, right or wrong” (p. 191). Ellis relays that Spellman’s version of civil religion also supported federal aid to Catholic schools (p. 193).

In contrast to Ellis, for whom Spellman must have loomed large as a Catholic Cold Warrior, McGreevy spends little time on the cardinal. Indeed, McGreevy’s 2003 book focuses on liberty (it’s titled Catholicism and American Freedom: A History) but Spellman appears on just one page. In chapter six, which covers the 1930s to the 1960s, Spellman is mentioned only in the context of a particular debate about academic freedom. The occasion is Bertrand Russell’s removal, in 1940, from New York City College post. Catholics at the time seemed to only care about “Russell’s views on sexuality and marriage” in relation to “common decency” (p. 176). The then Archbishop Spellman supported Russell’s removal, questioning the “wisdom of subsidizing the dissemination of falsehood under the guise of liberty” (p. 176). That’s it. Spellman’s vehement anti-communism and Vietnam War patriotism, as well as his support for the Civil Rights Movement, did not result in a more prominent place in McGreevy’s narrative on Catholics and the story of freedom in the United States.

In building her own story about the Church’s background and context of the Catholic Left, Nickerson successfully shows the power of Cardinal Spellman as a center-right force for millions of American Catholics during the Cold War. Spellman came into power during the high-tide of American economic post-war boom—a time which including powerful unions, the GI Bill, favorable home-lending, etc. This meant new parishes full of middle-class churchgoers. Returning to civil religion, this context also meant that Catholics benefited from the new “Judeo-Christian” alliance outlined by Kevin Schultz in his 2011 book, Tri-Faith America (Oxford).[4] Spellman and the American Catholic Church were helped by positive media images about priests and Catholic figures (pp. 28). Catholics had finally become accepted into the mainstream of American social, cultural, and political life.

In this context, Nickerson reminds us that Spellman built a reputation as an astute financier. Spellman negotiated better interest rates from banks for building churches, schools, and hospitals. He earned the nickname of “Cardinal Moneybags” for that work (p. 29). He still, however, desired government support for Catholic schools—and was bold enough about it to label Eleanor Roosevelt “anti-Catholic” when she criticized his position (p. 29). Despite his desire for the involvement of the federal government, Spellman nevertheless opposed the kind of ‘liberalism’ exemplified by President John F. Kennedy. Spellman also disliked activists, even while he supported the civil rights movement and “fought against racial discrimination in public housing” (p. 29).

Being a part of that mainstream meant that Spellman was fully integrated into Cold War politics. Per Ellis above, patriotism was his central civic virtues. This meant that Spellman supported U.S. actions in Vietnam (p. 27). For him and presumably other Catholics, it mattered that the South Vietnamese president, Ngo Dinh Diem, was Catholic. Catholics had long decried communism and socialism, but Spellman’s anticommunism lined up with that of President Kennedy. Nickerson asserts that this common ground “symbolized the arrival of Catholics into the cultural and political elite” in the 1960s—not only as oligarchic brethren but as leaders of it (p. 28). Spellman was committed to this plank of what Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. called the “vital center.”[5] With that, Spellman desired “total victory” in Vietnam (p. 27).

Michelle Nickerson, *Spiritual Criminals: How the Camden 28 Put the Vietnam War on Trial* (University of Chicago Press, 2024)

My favorite part of this section is how Nickerson reminds the reader that Spellman’s patriotic politics were, in fact, not indicative of the attitudes of everyone in the larger Church. There existed division and “disagreement among Western liberal Catholics over the meaning of human rights” and how Catholic Social Teachings should assist toward that end (p. 27). A singular but prominent figure with a different stance was Spellman’s pope.

Paul VI “denounced the war in Indochina” and the Vatican “did not take a unified stand on the Vietnam War” (p. 27). Paul VI spoke at the United Nations in 1965 about it being a “sacred duty” of world leaders to “establish global peace” (p. 27). The Pope asked Catholics around the world in October of that year to pray the rosary with the special intention of asking for “negotiations and peace” regarding the war (p. 27). Meanwhile, in that same year, Cardinal Spellman “traveled to Vietnam and spoke to American troops while wearing full military regalia” (p. 29). Apart from Spellman’s lack of concordance with the papacy of Paul VI, he also criticized Pope John XXIII and some of the changes of Vatican II. Nickerson notes that Spellman even opposed the usage of vernacular languages in mass. He also criticized John XXIII as incompetent (p. 28).

On the subjects of Spiritual Criminals, Nickerson relays that “Spellman disliked activists, especially Daniel Berrigan” (p. 29). One reason for the pointed dislike of the Jesuit Berrigan was that he spoke at the funeral mass of Roger LaPorte—the activist who self-immolated to protest the Vietnam War. Berrigan asserted that LaPorte was Christ-like in that his death was the fault of the “violence of others.” An angry Spellman “exiled” Berrigan to South America as punishment (p. 29). Nickerson notes the irony of Spellman’s chaffing under papal authority even as he was angered by members of his flock, meaning Berrigan and other young activists, defying his own authority.

Nickerson then, in the text, transitions to the long tradition of Catholic radicals who have “challenged the very structures and boundaries of the church.” For instance, they used “a corpus of church texts to counteract the long-standing Catholic tradition of sanctioning combat.” The next passages are about larger historical ideas and traditions, especially the development of the “just war” doctrine in Catholic theology. She is setting the context for why Catholic Leftists in the late 1960s could be seen as radical but also working within legitimate church traditions.

From Cardinal Spellman’s funeral at St. Pats [i.e. St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York]. From the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2020733139/

To me, the story of Spellman in this context highlights the center-right trajectory of the church in U.S. politics. That trajectory would harden into a firm conservatism later, with the anti-abortion activism of the 1980s and 1990s. That position has lasted to the present. But the period of 1960s saw a Catholic interest in a more capacious liberalism, as well as civil religion, evident in some of actions and positions of Spellman. The election and admiration of John F. Kennedy symbolizes that pre-Vietnam and pre-Roe centrism of Catholic politics.

—————————

[1] Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The ‘Objectivity Question’ and the American Historical Profession (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 69n9, 174n10, 203n62, 366n7.

[2] For more on Ellis, see the Special Collections entry on him at the Catholic University of American Library website: https://findingaids.lib.catholic.edu/repositories/2/resources/86.

[3] John Tracy Ellis, American Catholicism , Second Edition, Revised (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956; 1969); John T. McGreevy, American Catholicism and American Freedom (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2003).

[4] Kevin Schultz, Tri-Faith America : How Catholics and Jews Held Postwar America to its Protestant Promise (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). FYI: Schultz is a past S-USIH president.

[5] Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1949). For more details on the book, see its Worldcat entry.

[6] Ellis, 184.

0