Editor's Note

In this guest post, David Weinfeld of Rowan University offers an intellectual history perspective on political rhetoric that appears in the 2024 presidential election, specifically by exploring the origins of the term cultural pluralism in the work of Horace Meyer Kallen and in his conversations with Alain Locke. This post comes from a panel at the Biennial American Jewish History conference in May 2024, along with a recent post by Chad Alan Goldberg.

As the 2024 presidential election approaches, some of the largest and most controversial issues in American politics concern legal and illegal immigration, refugee policy, and the security of the country’s borders. Americans are concerned about who gets in, who stays out, and what those determinations mean for the future of the United States. It’s an economic question, to be sure (“they’ll take our jahbs!”) but it’s also a cultural one. What defines America and what does it mean to be an American?

It’s in this context that Trump supporters have labeled Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris, “DEI hire,” standing for “diversity, equity, and inclusion.” Harris, the current vice president and former senator from California, would be the first female president of the US. She is Black and biracial and Baptist and of Afro-Jamaican and Hindu Indian ancestry. She graduated from high school in Canada and from Howard University in Washington D.C.—the most celebrated of the historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Harris, a woman of color with a Sanskrit first name, is married to a Jew and is the American-born daughter of two immigrant parents; both would be firsts for a US president.

Like Barack Hussein Obama before her, Harris represents the hybrid identity and possibilities of diversity that Americans alternatively embrace and fear. For those who fear it, DEI represents not only affirmative action policies in hiring and university admissions, but also subversive ideas polluting American education, media, and culture, from Marxism and post-modernism to the social construction of race and gender to the placing of Islam and other “non—western” religions on par with their so-called “Judeo-Christian” heritage.

One hundred years ago America faced similar questions. With nativism on the rise following the First World War, the government responded with fear, passing the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, severely curtailing immigration from southern and eastern Europe, and effectively ending it from Asia (restrictions not undone until 1965). While many citizens, including numerous immigrants, opposed this Act, the restrictions found supporters among a resurgent Ku Klux Klan, who violently excluded Blacks as well as Jews and Catholics from their definition of American. Contemporaneously, Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey led a popular but unsuccessful movement for African Americans to return to Africa in the face of relentless racism back home, while Ivy League universities enacted restrictive quotas for Jewish applicants.

A small number of American intellectuals, mostly long forgotten, proposed a different path. One such figure was Horace Meyer Kallen (1882-1974), a German-born Jewish immigrant to Boston and philosophy professor at the New School for Social Research. In his 1924 book, Culture and Democracy in the United States, now a century old, Kallen coined the term “cultural pluralism.” He argued that what defined and represented the best of America was its diversity coupled with its commitment to freedom, democracy, equality, and inclusivity. Cultural pluralism served as a kind of intellectual precursor to what we now call multiculturalism, a foundational idea for DEI policies today. You can trace a crooked but clear line from Kallen to DEI, which makes sense, because Kallen was the prophet of DEI avant la lettre.

Kallen had fleshed out the idea without naming it nearly a decade earlier, in a 1915 essay in The Nation called “Democracy Versus the Melting Pot.” As World War I raged across the ocean, Kallen offered cultural pluralism to the US as a relatively simple idea that opposed not only bigoted nativism but also the American melting pot, which he regarded as a front for “Anglo-Saxonism.” He argued that different ethnic groups could and should retain their ancestral cultures as they adapted to modern life and integrated into the US economy and broader social fabric. Each group should further develop its own art and literature and music in America, in conversation with all the other groups doing the same. His metaphor for cultural pluralism was the harmonious “symphony of civilization.”

Cultural pluralism was the American advantage over a warring and discordant Europe. To Kallen, the preservation and development of diverse cultures would benefit those groups and America as a whole. He opposed immigration restriction but also the assimilationist ethos that coerced immigrants to abandon their cultures. He believed that only adaptable but cohesive communities, treated equally, could foster creative cultural development. In a society governed by cultural pluralism, groups should borrow and learn from each other to develop hybrid identities. Borders between cultures should be porous, but they should still exist to preserve communal integrity. Diversity required the preservation of difference within an egalitarian framework.

Today’s DEI framework, a descendant of cultural pluralism, has many critics, from the right and the left. Right-wing critics of DEI tend to privilege what they understand to be more “authentic” American culture associated with a white European heritage, with Christianity and especially Protestantism, with rural and small town communities as opposed to big cities, with conservative norms with regards to gender and sexuality, and usually (but not always) with a preference for economic individualism, limited government, and free market capitalism over unions, regulation, and the welfare state.

On the far left, meanwhile, Marxist scholars like Adolph Reed and Walter Benn Michaels have argued that DEI is just feel-good policy. It allows the ruling class to diversify, to place elites in the executive board rooms who can be men and women, black and white and Asian and Latino, and across the LGBQT spectrum, but changes nothing for the masses, especially workers. DEI, from this perspective, ignores class, which to these critics is far more important than all those other categories combined.

There is something to this left wing critique. The E in DEI signifies the word equity, and it’s unlikely that even the concept’s staunchest defenders would suggest that solving American inequality is simply a matter of instituting affirmative action programs, diversity statements, and multicultural activity fairs and speaking events. Those committed to social justice understand that a radical redistribution of resources will be needed to create a more equitable society.

And yet both the right wing and the left wing critiques miss the important contribution of DEI and by extension cultural pluralism, which is that culture matters. Culture is not only interesting. It is also important in understanding behaviors of different groups. Milton Himmelfarb’s old joke, that “Jews earn like Episcopalians and vote like Puerto Ricans” is funny but also an entry point into a discussion of why people behave the way they do—and how that can change over time.” Cultural pluralism insists that there is more to people than their social class. That people’s ethnicities and ancestries and religions can shape their behaviors. And that people can learn from each other and grow through social interaction and friendship with people who behave differently.

Though he first used the term cultural pluralism in print in 1924, Kallen later claimed he came up with it in 1906 or 1907 as a philosophy teaching assistant at Harvard, in dialogue with his African American student and Philadelphia native Alain LeRoy Locke (1885-1954). Annoyed by the racism he faced, Locke asked “what difference does the difference make?” But Kallen encouraged Locke to embrace his cultural difference just as he had come to cherish his own secular Jewish identity. They continued the conversation the following year at Oxford, while Kallen completed his doctoral dissertation and Locke studied as the first Black Rhodes Scholar. In November 1907, the Oxford American Club held a Thanksgiving Dinner but did not invite Locke. Angered by the slight to Locke, Kallen invited his former student to tea, solidifying the friendship and spurring further discussion of cultural pluralism.

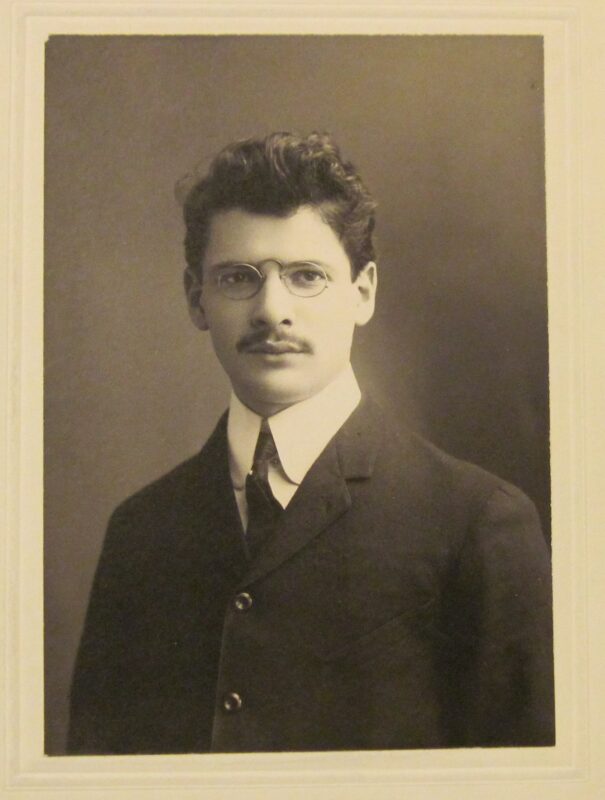

Kallen at Princeton University, in author’s collection.

Alain Locke at Howard University, borrowed from https://hiddencityphila.org/2021/06/alain-leroy-locke-father-of-the-harlem-renaissance-and-philly-lgbtq-hero/.

To Kallen and Locke, cultural pluralism was a form of cultural nationalism. For Kallen, that meant the promotion of Hebraism, or secular Jewish culture, and its political manifestation, Zionism, which he believed fully compatible with American patriotism. For Locke, who became a philosophy professor at Howard, that meant rejecting Garveyism in favor of the development of a hybrid African and American culture in the United States. He became the intellectual godfather of the New Negro movement, also known as the Harlem Renaissance, editing its bible The New Negro in 1925. For Locke, Black lives mattered, but Black cultures mattered too.

For these two American philosophers, cultural pluralism was not only about cultural movements; it was about friendship. Both men sought out environments where they could encounter people who were different from themselves, and not just meet them, but befriend them. In a 1955 memorial address for Locke, Kallen explained this idea of cultural pluralism as friendship. He encouraged diverse individuals to form friendships with this formulation: “I am different from you. You are different from me. Let us exchange the fruits of our differences so that each may enrich the other with what the other is not or has not in himself. In what else are we important to one another, what else can we pool and share if not our differences.”

The model environment for this intellectual exchange was the college or university, the classroom and the campus. In such an environment, the goal would be to not simply respect or tolerate differences but to appreciate and embrace them, to learn from them. The ideal would be to make friends that are different from you. Kallen and Locke spent most of their lives in the university, as have I. My experience has led me to embrace cultural pluralism.

To be sure, Kallen and Locke’s versions of cultural pluralism contained differences. Though Kallen faced significant antisemitism in the US, as a white Jew, his main fear was of the assimilationist American melting pot erasing Jewish identities and communities. Furthermore, when Kallen initially advanced cultural pluralism, he mostly ignored African Americans and Black culture. There was no room for jazz in his European cultural symphony, where he felt Jewish Americans belonged. Only after his decades-long friendship with Locke did he come to appreciate the African American contribution to American culture.

Locke by necessity saw things differently. A visibly Black man, he could not achieve complete assimilation into a searingly racist society. He wanted a seat at the table of American culture, just as he was denied a literal seat at the table of the Oxford American Club Thanksgiving dinner. He wanted Black culture to be respected. Amidst American diversity, he wanted equity and inclusion. A gay man whose sexuality was an open secret, a progressive with radical sympathies who died before Brown v. Board, and a middle-aged convert to the Baha’i faith, Locke never felt entirely comfortable in the devoutly Protestant and politically moderate African American mainstream. He sought the kingdom of culture as refuge and cosmopolitan ideal.

Despite these differences, both men understood the value of honoring their heritages while embracing diversity. They demonstrated that interethnic friendships not only fostered harmonious group relations but also spurred cultural and intellectual development. Kallen and Locke both appreciated the modern university as a great stage for American diversity. The symphony of civilization plays loudly, and beautifully, at institutions of higher learning. Ideally, university DEI policies encourage students to listen, participate, and form friendships, and then through those friendships, to learn and create and flourish.

Today, huge sums of public and private dollars are spent on DEI programs: some are effective, others are not. Channeling Kallen and Locke, perhaps we should think of DEI not as an administrative division or a particular set of policies, but as an ethos rooted in the principle of friendship. Locke and Kallen would have believed in the spirit of DEI, that the ethnically, religiously, and culturally heterogenous university provides a vastly superior learning environment to the more homogenous campuses of the past, in large part because of the friendships that could be made there. They would have also agreed that to foster such friendships in universities, or workplaces, or other public spaces, the US would need a generous and tolerant immigration policy. Only then could we hope to undo the persistent legacy of American bigotry on route to a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive future, where friendships are made among strangers and neighbors alike.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’m sorry, but calling Adolph Reed, someone who endorsed voting for both Hillary Clinton and (twice) Joe Biden, “far left” is ridiculous. U.S. politics are so reactionary that positions which would be moderately social democratic/center left in Canada, Mexico, the UK, France, Germany, or Australia are labeled “far left” as if it is extreme to believe in things like single payer healthcare. This is ridiculous.

I just read this post and find its defense of cultural pluralism interesting but not very convincing. Culture does better as a description of how people behave than as a reason for or explanation of that behavior and insofar as we racialize it (black culture, white culture, Jewish culture), it works only by relying on the appeal to racial identity which it supposedly makes irrelevant. I’d be interested to know David Weinfeld’s response to this old article “Race into Culture” https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1343825.pdf — especially to the part that argues that cultural pluralism is an oxymoron.

Also, with respect to the comment above, Adolph urges you to vote for Kamala too (as do I). I don’t know if that’s “far left” (but apparently some people think she’s a communist).