The Book

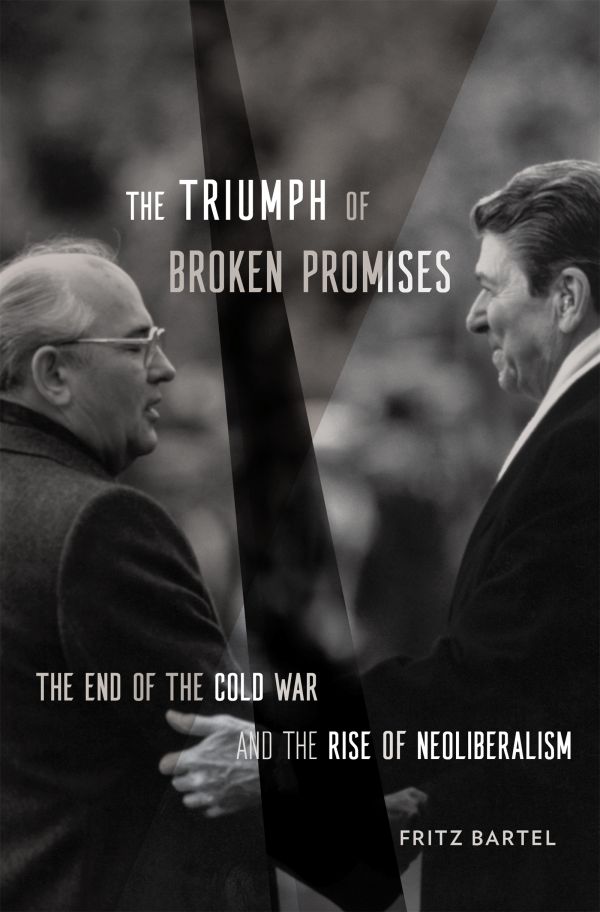

The Triumph of Broken Promises: The End of the Cold War and the Rise of Neoliberalism

The Author(s)

Fritz Bartel

Fritz Bartel’s The Triumph of Broken Promises: The End of the Cold War and the Rise of Neoliberalism provides a new history of the peaceful end of the Cold War. Bartel draws parallels between how Western and Eastern Bloc countries handled economic challenges. In both cases, politicians broke promises of economic development. Capitalist societies came out ahead because capitalist leaders were more effective at imposing “economic discipline.” This explains two defining 20th-century events: “the peaceful end of the Cold War and the rise of neoliberal capitalism.”[1] The Cold War was a race “to make promises, but it ended as a race to break promises.” Neoliberal democratic capitalism triumphed because it could nimbly break promises. “Communism collapsed because it could not.”[2]

The book has a fascinating feature: its focus on the 1973 oil crisis. This crisis unleashed economic forces that ended the Cold War. But it also produced the “neoliberal global economy of the late twentieth century.” The economic forces unleashed were profound, covering not only oil but also financial and economic power. These events altered “the competition between democratic capitalism and state socialism.”[3] Another central focus of the book is on German Reunification, which moved faster than anyone expected, again owing to economic forces.

I learned a great deal from the history in the book. I appreciated the insightful structural analogies. The politics of the capitalist West and the communist East are more aligned than I knew. Nevertheless, I have three objections.

First, the theme of “broken promises” does not fit the careful historical work of the book. The theme arises in cases where politicians overpromise good economic outcomes, only to have economic forces expose those promises as false. But there’s a more straightforward way to understand these political and economic policies. The 1950s-1970s saw significant productivity gains from the spread of new technology, a pace that could not continue forever. Politicians of that era had come to expect high, broad-based growth. Citizens did too. Those broad social expectations were simply part of social life. However, the slowdown in growth was inevitable because the incredible pace of growth was a historical outlier. Political overpromising of economic outcomes was thus a contingent feature of changing expectations of that time.

The theme of broken promises thus felt like an interruption from Bartel’s narrative. His comparisons shed light on shared economic expectations and promises in socialist and capitalist nations, but then we read something like, “And these promises were broken.” But politicians’ overpromising was not the ultimate explanation of political instability. The ultimate reason is that post-WWII economies set high growth expectations, and when those expectations turned out to be misguided, politicians came under pressure. That’s why they broke promises. Economic development made that impossible. Overpromising was just the response to projecting previous economic conditions into the future.

That leads to my second concern. Which political leaders do not overpromise? Ancient tyrants promised to control the weather, and failed, and medieval kings and priests vowed to rid the land of heresies, and they failed too, as the Reformation showed. Early modern liberal regimes promised an end to superstition. Marxists vowed that historical forces would create a new human being and endless prosperity. Everyone overpromises in politics. Indeed, that is one of its distinguishing features as such. I saw far too little from Bartel comparing Cold War overpromising to political life itself. And so, I didn’t find the theme of broken promises helpful.

My final point focuses on the conclusion. Bartel claims Eastern bloc peoples played a “heroic role” in fighting repression and creating “their own future.”[4] Yet Bartel finds something significant to lament:

… we can see that one of the central contradictions—perhaps the central contribution—of the collapse of communism was that the seat of government was returned to the people only so that their power to resist the government could be transcended. The end of the Cold War, we must conclude, was the moment in which the people’s power peaked and the moment in which it was overcome.[5]

Bartel seems to think Eastern Bloc nations did not increase their democratic freedoms. At least not very much. So, presumably, Bartel believes that the collapse of communism in Poland did not make it substantially more politically free. It went from communist domination to capitalist domination.

But standard measures of democratic functioning don’t agree. The Economist Democracy Index and the V-Dem Democracy Index show that Poland’s degree of democracy rose dramatically between 1985 and 1995. Bartel does not provide us with arguments against these measures. His narrative contradicts the data. That is disappointing, given Bartel’s careful use of data elsewhere in the book.

The Triumph of Broken Promises is an exemplary contribution to the history of the Cold War. Many of its claims are illuminating and well-defended. Unfortunately, Bartel’s narrative can obscure the insights in this important historical work.

[1] Bartel 2022, p. 3.

[2] Bartel 2022, p. 5. Repeated on p. 333.

[3] Bartel 2022, p. 332.

[4] Bartel 2022, p. 344.

[5] Bartel 2022, pp. 344-5.

About the Reviewer

Kevin Vallier is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Bowling Green State University. He is the author of four books, most recently All the Kingdoms of the World: On Radical Religious Alternatives to Liberalism (Oxford UP 2023). He can be reached at [email protected].

0