Editor's Note

This is part 7 in my series on Lauren Lassabe Shepherd’s Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & the Campus Wars in Modern America. You can find past posts at this link.

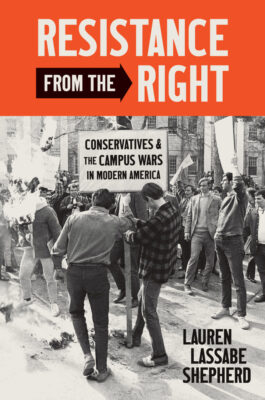

This is the cover of Shepherd’s *Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & Campus Wars in Modern America*. It shows male students protesting against Students for a Democratic Society by burning an SDS effigy at Harvard in 1969.

Few issues divide the hard left from the hard right more cleanly than their general views on the military. This was especially true in the context of the Vietnam War. This division fed a number of actions—in terms of vocal and material support—at higher ed institutions by the campus right. It was, to them, a national duty. In Resistance from the Right, Lauren Lassabe Shepherd regularly reinforces the fact that YAF and campus conservatives “characterized stalwart support of the military as patriotic” (p. 91). Beyond, however, a general upholding of troops and the war in Vietnam, the actions of student conservatives centered on support for military recruitment and draftees, for military research at universities, and for the presence of ROTC on campus.

To set the stage for responses by campus conservatives, Shepherd recounts the scale and intensity of anti-recruitment events in the nation. In the time around 1967 “Stop the Draft Week” (Oct. 16-20), more than twenty of these protests occurred across the nation (p. 54). Events—which included at times “physical interferences with recruitment”—occurred at Northeastern, Harvard, Brown, Stanford, Princeton, Brooklyn College, Oberlin College, Williams College, and the Universities of Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania (p. 54-55). Shepherd does not neglect the fact that student progressives also opposed corporate recruitment for the war industry, especially Dow Chemical. An anti-Dow protest in Madison during October 17-18 which involved a building sit-in resulted in police violence (p. 53).

The Madison event resulted in what Shepherd calls “retributive backlash” from both “administrators and conservative students” (p. 53). A UW-Madison Young Americans for Freedom member and law student, David Keene, composed a response to the “Dow Strike” that reached the YAF’s national newsletter, New Guard. Keene argued that the student left actually tried to control the terms of speech through authoritarian protest and demonstration tactics (p. 54). Their hypocritical violence (e.g., choking student peers, striking admins, attacking police, disrupting UW operations) and general anti-liberalism necessitated a military presence on campus. It was just and right for police and the National Guard to use tear gas and be physically rough (p. 54). It was easy for campus conservatives support law and order via the military.

At Oberlin College, Shepherd relays, conservative students supported the police protection of a navy recruiter on campus who had been surrounded by over a hundred students. They praised police for disbanding the crowd with tear gas and fire hoses (p. 55).

Shepherd reminds us that campus conservatives and YAF members approved of Selective Service Director Lewis B. Hershey’s Memorandum No. 85 which required constant personal possession of one’s conscription card (p. 55). Lack of possession put one’s draft deferment at risk. Hershey also empowered local draft boards to revoke deferments for those who protested “war-related recruitment” (p. 55). All of those demonstrated support for the military and the Vietnam War. Patriotism and national pride rested on allowing the war machine to function smoothly.

Support for military research was another platform plank for student conservatives. They touted the attractive job opportunities in corporations affiliated with war production. Campus conservatives emphasized the diverse portfolio, for instance, of Dow Chemical—which produced “vaccines, antifreeze, and Saran Wrap in addition to napalm” (p. 56). Emphasizing consumer complicity is a common tactic for neutralizing criticisms of corporations that profit in a war-time footing. Disentangling the negatives of less desirable products is too much to ask of corporations that are trying to service the needs of military operations.

Conservative observers of higher education, Shepherd recounts, also emphasized “the benefits that war research dollars brought to their institutions” (p. 56). While not all of these grants went directly to military research, in the fall of 1968 the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) accepted “nearly $80 million in research funding” (p. 32). Shepherd lists a number of other universities that received $30-40 million: UCLA, UC-Berkeley, Stanford, Harvard, Columbia, and the Universities of Michigan and Wisconsin. The University of Alabama obtained $55 million in the 1958-1967 period. Shepherd relays that “42 percent of the domestic military payroll” was spend in the South (p. 32). Economically, then, the federal government and the military employed massive numbers of people with an interest in maintaining the status and prestige of their institutions.

To Shepherd, the messages from campus conservatives often found receptive ears among fellow students. A 1968 antiwar research demonstration at the University of Michigan, to protest the reception of a $10 million Depart of Defense grant, did not change the minds of students. A student vote on the cessation of classified research activities found that 61 percent of students came out against the measure. A majority of students favored the continuation of that work. In a 1967 anti-recruitment protest (targeting Dow Chemical) at Harvard and Radcliffe resulted in numerous students placed on probation and a larger sentiment, expressed in the media by fellow students, that the demonstrators were punished “too lightly” and should have been expelled (p. 56-57).

Shepherd also reminds the reader that college students and graduates did not automatically reject work in the war effort. In late December 1967 article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, a reporter relayed that: (a) recruitment quotas were met by all branches of the military, (b) 2505 graduates had been admitted to officer training schools, (c) the U.S. Navy’s competitive acceptance rate was 30 percent, and (d) that the CIA visited 115 higher education institutions to recruit students in STEM, economics, political science, geography, and geology. Dow Chemical, in addition, still hired 1300 college graduates (p. 56).

In resisting the military and the presence of it on campus, as well as the Vietnam War generally, the campus left targeted the Reserve Officers Training Corps. Knowing this, the campus right wove its anticommunism and patriotism with defenses of the military. According to Shepherd, they also used acts of violence against the military, perpetrated by radicals, to discredit the entire peace movement. In the case of the ROTC, in the fall of 1969 alone, campus conservatives could exploit “80 bombings and cases of arson directed at ROTC buildings and draft centers” (p. 157). These events, in turn, allowed the Nixon administration to seek “1,000 additional FBI agents to investigate campus radicals” (p. 157). Campus conservatives and YAF members also publicly supported ROTC programs.

First things first, “conservatives publicized the hypocrisy of [student] radicals who condemned the ROTC for cultivating violence while detonating explosives and starting fires for peace” (p.159). No matter the fact that leftist radicals almost always targeted empty buildings (with advance warnings provided), campus conservatives portrayed leftists as “nihilist criminals” (p. 159). The destruction of property, whether private or public, has always been trumped up as an unacceptable form of violence by the right.

Campus conservatives also philosophically defended the ROTC presence in higher education. They maintained that “ROTC programs satisfied university missions by helping students advance their careers as officers and by boosting the defense capabilities of communities, municipalities, and states.” They also argued that “a military presence on campus” helped the institution in defending individual and academic freedom (p. 159).

Shepherd found several primary archival sources that demonstrated ROTC support on campus by conservative students. A 1969 editorial in Duke’s Carolina Renaissance, submitted by a YAF member and given front-page status, forwarded that the ROTC: is central to helping replace the draft; provides high-quality leaders to the military; and, brings a more humanistic vision to the country’s military apparatus. At North Carolina State University, student supporters noted practical factors—that “guys join ROTC…[for] the scholarship money” or simply to be an officer rather than a GI if they must go to war (p. 160). In the end, ROTC represented the fact, for campus conservatives, that “military service was ultimately a duty to country” (p. 160).

Patriotism meant, for YAF members and campus conservatives, a commitment during wartime to all the ways that the military touched universities and campus life. One wonders, however, how this support might vary during peacetime—or at least how a peaceful period lowers the emotional and practical commitment to all aspects of recruiting, military research, and the ROTC. I have seen no historical study that has attempted to capture, or measure, that support in, say, the 1975-1990 period.

No matter what might happen later in peacetime after the Vietnam War, late 1960s campus conservatives highlighted their patriotism by supporting the U.S. military any way they could.

The series continues next week. – TL

0