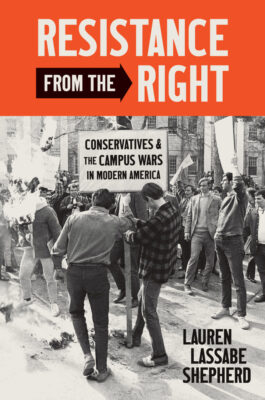

This is the cover of Shepherd’s *Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & Campus Wars in Modern America*. It shows male students protesting against Students for a Democratic Society, by burning an SDS effigy, at Harvard in 1969.

In her 2023 book, Resistance from the Right, Lauren Lassabe Shepherd raises a number of issues that deserve our full attention. Whether or not you work in the academy, what happens there has a way of emanating outward—into K-12 education, adult education, scholarly societies, libraries, culture, government, politics, and society. Tensions felt in U.S. higher education reverberate even in institutions well outside of the boundaries of this country. For these reasons, meditating on Shepherd’s close look at late 1960s conservative activities in, and around, higher ed campuses can help us understand downstream effects felt today.

Full disclosure: Lauren and I are friendly colleagues. We have met in person at the last two S-USIH conferences. We are both part of a writing group that meets monthly, wherein I read some of the chapters in draft form. Lauren gave me a shout-out in her book’s acknowledgments and I am a fan of her work. We also have some larger shared experiences and perspectives. We both grew up in conservative surroundings. We have both worked in higher ed administration (I still do). We are both contingent faculty who take our historical work seriously. Given those shared background elements, in today’s post—and in the planned ones that follow—I will attempt to be objective about her book and its topics. I will even share a few criticisms and note some missed opportunities. Overall, however, my plan is simple: share my responses to her work and arguments.

The book’s full title (Resistance from the Right: Conservatives and the Campus Wars in Modern America) does not provide a date range, but the pages focus on 1967 to 1970. You might not think that her relatively narrow timeframe would capture so many still relevant concerns, but it does. Her thesis captures some of past-present connections that helped feed her work. Phenomena like cancel culture, deplatforming, and “lamentations of ‘wokeism’ and critical race theory…can be understood” as tactics and battles “in conservatives’ decades-long war against the academy and the cultural changes that liberal education champions” (p. 3). To better understand the sources of this war, she homes in on the “right-wing students of the late 1960s” who, “following the guidance of anti-New Deal elders who sponsored them financially and professionally, participated in an astroturf mobilization against the so-called liberal establishment in higher education.” These young conservatives would “become known as the new Right in the 1970s,” but “used the skills they learned in college to drive American politics and culture” in their preferred direction, using the “Republican Party as their vehicle” (p. 3).

My first reaction to this thesis was, wait, wut?! They found their tactics in this short period of time? How can a 50-plus year trajectory coalesce so quickly?

It is hard, however, to ignore the well-known and influential conservative names that arise in her work, whether as influencers or as the influenced: Bill Buckley, William Volker, Charles Koch, Richard Mellon Scaife, Richard Viguerie, Newt Gingrich, Bill Barr, Jeff Sessions, Karl Rove, Pat Buchanan, David Duke, Paul Weyrich, R. Emmett Tyrrell, and others. I know the conservative movement reasonably well, but was still surprised by the range of figures captured in the brief time frame of Shepherd’s study.

Also, in spite the range of names cited and people influenced, a lot of the efforts in this period were bankrolled and chartered by a “only a few dozen powerful conservatives.” The work of this smaller group, however, was “not done in secret.” Rather, the “movement makers…loudly proclaimed the service to the counter-left revolution.” Shepherd says they have documented everything clearly, even to the point of being “prolific” about “their own success” (p. 4). They have laid out their efforts with regard to the academy for all to see.

My goal in the posts that follow will be, again, to highlight Shepherd’s main points and chapter coverage. I want to talk about the conservative long-game in higher ed (a “long con”?), but also how that game has affected the work of their opponents–whether neutral, liberal, or radical. It is important to see how tactics from the left and right have been used, by warring factions, to manipulate students, faculty, and administrators over time. By covering the tactics and making them familiar we can, perhaps, learn to look past them to the deeper ethical motivations of on-campus activists. We can them examine those motivations and assumptions in relation to the core mission and activities of higher education.

Apart from directly covering Shepherd’s book, I will also, on occasion, use her work to extend outward on other related, more current topics. It will be our jumping off point. See you next week! – TL

0