The Book

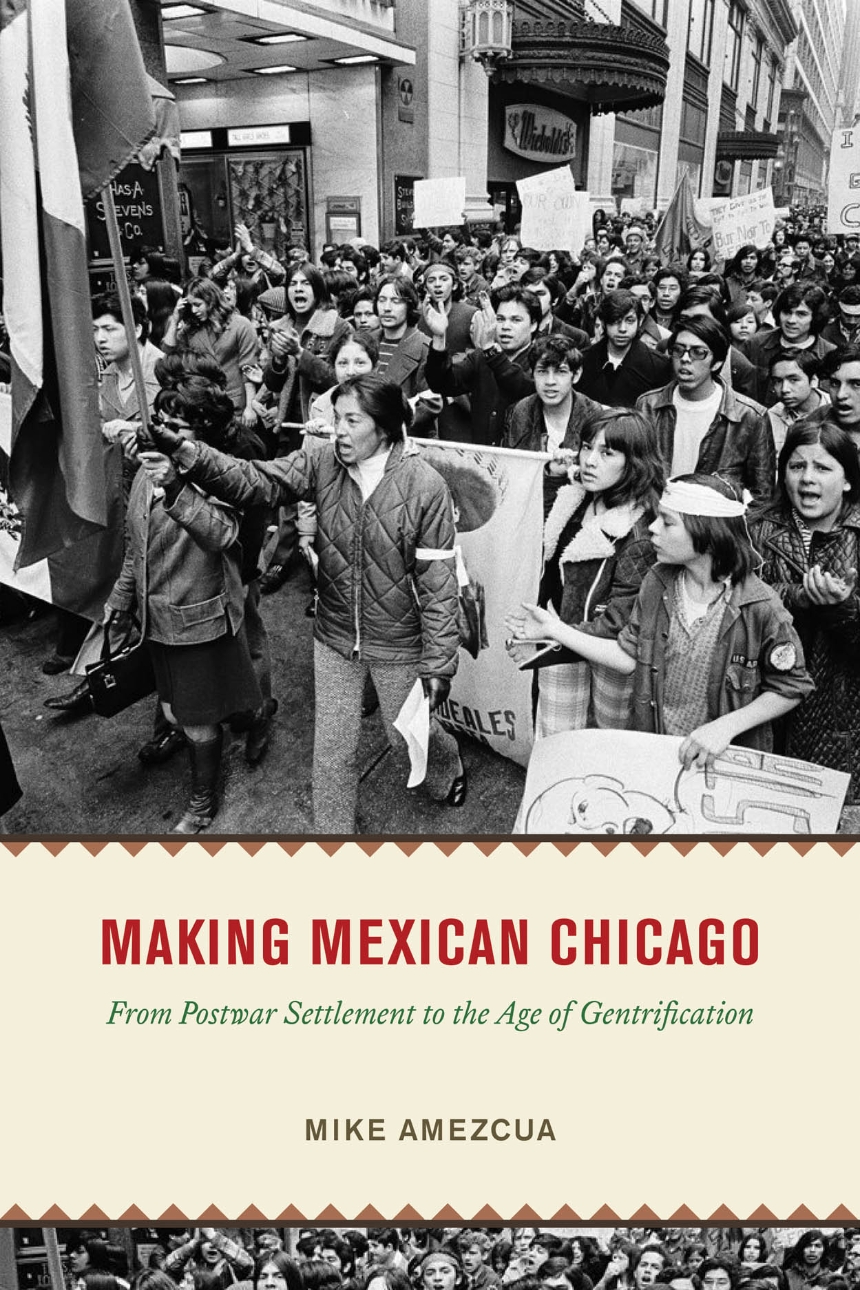

Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification

The Author(s)

Mike Amezcua

Mike Amezcua’s 2022 Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification chronicles how the historic racialization and otherization of Mexicans as “perpetual foreigners, illegals, [and] criminals” influenced the formation of both figurative and geographic communities and development of Mexican identity in Chicago.[1] Amezcua shows how immigration policies alongside federal, state, city, and neighborhood politics affected community members and groups. He does this by privileging the stories of Chicago citizens on the ground rather than policymakers. By looking at several central Chicago neighborhoods’ post-WWII transformations into hubs for the Mexican community, he shows how “Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans were placemakers and community builders who shaped their neighborhoods and instilled in each other a sense of belonging, despite the odds.”[2] The odds included the fact that many in the city’s leadership and many fellow Chicagoans didn’t always want a Mexican community; Chicago’s Mexicans and Mexican Americans often found themselves positioned as a buffer between Black neighborhoods and white immigrant neighborhoods, or even between Black and white neighbors in the same neighborhood as was the case in Back of the Yards and Little Village. In addition to reinserting the critical history of Mexicans in Chicago to a narrative that is often construed as Black and white, Amezcua also intervenes by showing how “Mexicans and Mexican Americans were not only targets of the conservative revolution […but] they also helped to shape it.”[3] The book analyzes how Mexican Chicago was made and unmade in the midst of “destabilizing episodes of federal and municipal disinvestment, economic restructuring, the immigration carceral state, political disenfranchisement, and predatory corporate reinvestment.”[4] Each of the book’s five body chapters surveys a different neighborhood significant to Mexicans in Chicago, from the 1940s to the early 2000s, to contend with how that space impacted Mexican identity formation and community. Chapter 1, “Crafting Capital,” serves as the book’s introduction; Chapter 2 covers the Near West Side (including Hull House) in the 1940s and 50s; Chapter 3 looks at Back of the Yards (Las Yardas) in the 1940s through the 1960s; Chapter 4 investigates Little Village (La Villita) from 1960 to the mid-1970s; and Chapters 5 and 6 analyze Pilsen in the 1960-70s and mid-1970s to the early 1990s, respectively. (The conclusion takes the reader into the twenty-first century.)

This book does a great deal in 250 pages, featuring impressive use of photos from individual’s personal collections, showing the tremendous amount of oral history gathering Amezcua engaged in for this project. He enlivens the history of community-building through the incorporation of real people and their stories, who then recur as characters in subsequent chapters. For example, Anita Villarreal, a real estate agent turned community organizer turned activist, is introduced to the reader in the introduction and then shows up in several more chapters as her investment in making Mexican Chicago grows. Amezcua threads these types of individual stories with meeting minutes from small, intensely-local grassroot organizations and compliments these with broader and more familiar historic voices (such as US immigration policy, and Chicago’s two Mayor Daley administrations). This symphony provides a personal lens for understanding 60+ years of history in a huge metropolis. Amezcua’s method and methodology is a model for those coming up in the field; it recovers and centers those often left out. This work sits beautifully at the intersection of narrative history and social policy, showing innovative intervention in a field that often has texts on either side. That said, readers without deep knowledge of the city of Chicago will find the text difficult at times; chapter-specific maps or more maps overall would help, as would even a dramatis personae. While the sectioning of the chapters by neighborhood and decade is useful, professors may struggle to use sections of the book since historical figures return from chapter to chapter and because policies discussed in one chapter have impacts in subsequent chapters. Still, scholars and students invested in the Mexican and Latine immigrant experiences in North America; in Chicago Field Studies and Urban Studies; in the development of conservative and progressive politics in communities of color; and those interested in place-making, community building, and identity will relish this book. It traverses overlooked parts of US history by providing a genealogy of macro/micro sociopolitical moments that have influenced society’s modern-day conceptualizations around Mexicans, not just in Chicago but in the US more broadly, and it does so with voices so far omitted from much of the academic record.

[1] Mike Amezcua, Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification (The University of Chicago Press, 2022), 37.

[2] Amezcua, 14.

[3] Amezcua, 14.

[4] Amezcua, 246.

0