Editor's Note

This is part two in a two-part series about indexing. The first entry was published on Wed., Feb. 21.

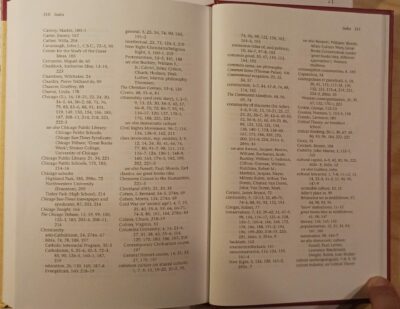

Here are two pages of the index to my own book. It is a mix of proper names and larger ideas. The key words to my argument appear on the next two pages.

Apart from learning to study them, I have also produced an index. Indexing my own first book (The Dream of a Democratic Culture, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) was an enjoyable and rewarding experience. That said, the task of indexing arose because I had no choice. My first-time academic work was published outside of an academic position, so I had no departmental or college-based subvention for editing or indexing. (This is yet another hidden resource hazard for contingent academic employees). My limited resources meant, after a conversation with my spouse, that I would invest in a thorough copy-editing job. Indexing, then, would by necessity come from me.Despite being under the gun, I knew the contents the best. I also knew what I wanted to emphasize for readers related to my argument and major points. I had firm ideas, in my special case, of how my work might be helpful to those currently involved in the activities about which I wrote. I had a feel for how the index might be used by various audiences, whether general, academic, or in the great books community.

To this day I am proud of that indexing labor. It did not feel like dead end work to me. While it was my first attempt at it, and even if a professional indexer might have done things differently, it felt good to me. To this day, almost eleven years later, I think I would be happy, time permitting, to index my next book—if I get the privilege of publishing one.

To this day I notice when a book has a slipshod or inadequate index. While my reviewing work has slowed over the last few years, I have still been reading new works. Recently I finished two with bothersome indexes that did not do justice to the author’s labors. Why spend years writing a book to have the publisher undermine your book as a tool for others?

I totally get why people chose and need indexers. It is unrecognized labor in the overall sphere of book production in academia. That said, I think authors might be surprised, later, how much a good index will help them as well as their readers. I have made use of my own index several times in the ten years since my book was published.

Outside accountability could also help. Perhaps we need to note, in our reviews, whether or not an index was was well done? Perhaps academics can make a point of emphasizing with their publishers that they expect the index to meet a certain standard? If publishers have been increasing pressure on authors to only include minimalists indexes (i.e., cutting funds, rushing the process), perhaps our professional organizations can produce some minimum standards of guidance?

With regard to efficiency, I think there may be an opportunity for artificial intelligence to make itself useful to writers, especially in history. With the proper copyright/intellectual property protections, as well as solid prompts for inputs (which can only come from the authors themselves), I think a AI tool might be really useful. It can take care of the baseline labor, enabling nonfiction authors to intervene at an advanced editing step.

In sum, believe all non-fiction writers, but historians in particular, need reevaluate the labor of indexing. We should value it as an art of bookmaking. We should value good indexes. Historians cover so many facts—people, institutions, ideas, and dates—in their works. Intellectual historians, moreover, work at highlighting how ideas underly, and guide, events. Readers deserve the assist of a solid index that underscores those ideas. Whether we construct the indexes ourselves or have others do it for us, let us give those tools of bookmaking the time and energy they deserve. – TL

0