The Book

Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?: Essays

The Author(s)

Jesse McCarthy

The title of a book tells the reader a lot as they anticipate sifting and gliding through the arguments, reflections, and style(s) of writing. In an age where there has been a renewed discussion about “the possibility of reparations as payment for racial injustice in the United States” (225), Jesse McCarthy’s sampling of Gil Scott Heron’s eponymous 1970 song/poem prompts the reader in a certain manner. While debates about the material and monetary debt that the US owes black people might be generative, the interrogative title indicates a loss, a debt, a kind of re-wounding, that cannot be quantified or measured numerically. It could be that the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow, and anti-black terror have left damages that “cannot be accounted for in the only system of accounting that a society recognizes” (233). For McCarthy, the reality of the unquanitifiable does not simply lead to perpetual black mourning; it is a reminder that in addition to wealth re-distribution, black people need to strive for “freedom from domination, community control, and justice before the law” (227). In the tradition of Du Bois, these are the higher ideals that black people should aspire to and pursue.

In addition to the Gil-Scott Heron inspired title, the sub-title anticipates the style and approach that McCarthy takes as he guides us through an array of subjects, debates, and figures with dexterity and generosity. This is a book of essays and as the author underscores, alluding to the etymology of the word, an essay is an “attempt,” an experiment, a sketch at something. Or as he puts it, the book is a series of “eccentric but serious attempts to synthesize and connect different bodies of knowledge and their relationship to race and black culture” (XVII). Alluding to the work of the late Cheryl Wall, McCarthy draws on the essay as form to address exigent concerns and to incite renewed ways of thinking about blackness, politics, aesthetics, freedom, and so forth.

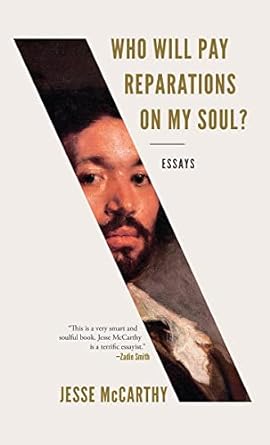

McCarthy brings together a wide range of discourses in a manner that combines rigor, clarity, playful juxtaposition, and charity to his interlocutors. He skillfully moves from reflections on Juan de Pareja as the unaccounted for Other in Foucault’s analysis of Las Meninas to an appreciation of Toni Morrison’s humanism to reflections on trap music as contemporary Du Boisian sorrow songs that provide a soundtrack to late capitalism. This assemblage of essays slides from an open letter to D’Angelo after his fourteen year hiatus to a personal account of the terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015 to a rethinking of the yearning to recover a black Harlem, especially when the “black” is narrow and averse to a Gilroy-inspired trans-Atlantic blackness. McCarthy creatively compares Walter Benjamin and Kara Walker in a manner that underscores the importance of allowing our “daily routines [to be] interrupted” (50) even as we cannot escape the storm of progress. The author provides a laudatory account of Fred Moten’s corpus, comparing his essays and poems to the sounds of golden era hip hop, especially an album like A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory. In addition, he offers critical engagements with the more pessimistic side of black studies, exemplified in the work of Ta-Nehisi Coates and Frank Wilderson. McCarthy’s theoretical scope is wide and his geographical range – Harlem, Paris, Nigeria, London, East Atlanta—is just as expansive.

There is an interesting but subtle tension that reverberates throughout these essays. On the one hand, the title of the book suggests that racial justice will involve more than formal political solutions or State-sponsored compensation to black people. In fact, McCarthy quotes Alexis de Tocqueville on just this point (145-146). At the same time, the author is very aware that black people have been attracted to a republican tradition that understands liberty in terms of non-domination. Within this tradition, law is what protects citizens from arbitrary power, coercion, and being reduced to what Agamben calls bare life. As McCarthy puts it, “The black man in America has often been imagined as an outlaw, but in truth blacks more than any other group have fought for the sanctuary of the law, seeing in it their best weapon for securing freedom from domination” (232). While there is much truth to this point, I wonder if this affirmation of law as sanctuary needs to be held in tension with another enduring predicament – the law of Western sovereign nation-states being an opportunity to sustain and solidify arrangements of domination and decimation. Among many other examples, one could think here of Native American and indigenous traditions, for whom being brought under the law as domestic dependent nations, continues a legacy of settler colonial occupation. But of course, the form of the essay at its best leaves us with unresolved tensions and frictions. McCarthy’s book is an enjoyable and challenging experience in part because of how he beautifully stages and thinks within these tensions.

About the Reviewer

Joseph Winters is the Alexander F. Hehmeyer Associate Professor of Religious Studies and African and African American Studies. He also holds secondary positions in English and Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies. His interests lie at the intersection of black religious thought, African-American literature, and critical theory. Overall, his project expands conventional understandings of black religiosity and black piety by drawing on resources from Af-Am literature, philosophy, and critical theory. His research examines how literature, film, and music (especially hip hop) can reconfigure our sense of the sacred and imagination of spirituality.

Winters’ first book, Hope Draped in Black: Race, Melancholy, and the Agony of Progress (Duke University Press, June 2016) examines how black literature and aesthetic practices challenge post-racial fantasies and triumphant accounts of freedom. The book shows how authors like WEB Du Bois and Toni Morrison link hope and possibility to melancholy, remembrance, and a recalcitrant sense of the tragic. His second book project (under contract with Duke University Press) is called Disturbing Profanity: Hip Hop, Black Aesthetics, and the Volatile Sacred.

0