The Book

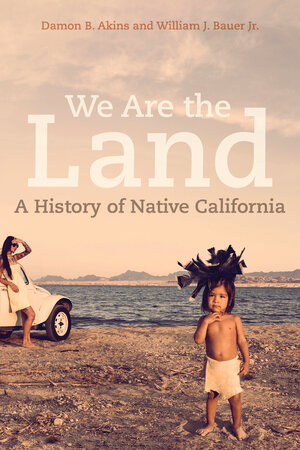

We Are the Land: A History of Native California

The Author(s)

Damon B. Akins and William J. Bauer Jr.

In We are the Land, historians Damon Akins and Round Valley tribal member William Bauer Jr. offer a synthesis of California Indian histories, revealing the unique diversity and nuances to tell a more complete story. As they assert in the introduction, “Rather than being peripheral to or vanishing from California history, Indigenous people are a central and enduring part of the state’s history because of their relationship to the land.” (Akins & Bauer Jr. 2022, 3) This forms the foundation of their argument: California is a location of two conflicting ideas—a place and an idea constructed on a dream. As a place, California, chapter 1 begins with creation stories of multiple tribal nations which centers California Indian ideologies as a place-based identity and explains their land stewardship roles. In contrast, many non-Natives came to see the dream of California as a destination filled with abundant resources to be monetized and exploited. Despite this, contemporary place names illustrate a lasting California Native presence. City names like Azusa, Petaluma, Tehachapi, Yucaipa; and county names Marin, Solano, Sonoma, Tuolumne, and Yolo, are but a few examples. As the authors assert, “Despite the long and rich history of Indigenous people in California, historians, anthropologists, and everyday people disconnected California Indian history from California history.” (Akins & Bauer Jr. 2022, 2) In part, this book represents an antidote to the ubiquitous disconnection and an assertion of California Indian survivance and resilience.

California Indian history as a topic is quite immense and many historians would not contemplate tackling it. Earlier publications include James Rawls’ Indians of California: The Changing Image and Rupert Costo’s Natives of the Golden State: The California Indians. Akins and Bauer skillfully navigate the complexities and bring the reader on a journey to better understand California Indian survival, and more than that, but also revitalization and activism. Of course, the legacy of three settler-colonial powers is exposed, but the authors note that is not the end of the story. Divided into ten chronological chapters interspersed with “Native spaces” vignettes on areas like Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, San Diego, Ukiah, and the furthest Rome, Italy, they move beyond the familiar narrative of placing Native American history in the distant past and instead connect past, present, and future.

A challenge to the invisibility of Native American histories, stories, voices, and experiences, the chapters detail the changing environment. Chapters 2-3 discuss the first waves of settler-colonialism and devastating ecological impact of Spaniards clearing land for pastoral and agricultural fields along with introduction of domesticated livestock numbering in the thousands. This connects to the Spaniards’ failure to recognize tribal peoples’ agricultural practices and represents an attempt to sever their relationality and cause estrangement to the land. Chapters 4-6 dive into the shifting labor market and how mission secularization and the Gold Rush accelerated and compressed the destructive economic shifts as California gained statehood with a focus on Native American land dispossession and vicious state policies. The 1850s and 1860s represent a particularly violent time of terror. Chapter 7 traces the historical practice of California Indian alliances and coalitions leading political action and legal challenges throughout the 20th century. Boarding schools and its legacies are also evaluated. Chapters 8-9 track the continued formation of a California Indian identity and dive into distinctive legacy of federal policies like termination but also continuation of political and cultural movements. The authors show how California Indians do not necessarily wait for the political or educational systems to catch up, rather they work on building alliances to collectively lead changes. Chapter 10 examines the social, economic, political, and cultural development in the aftermath of Indian gaming. The authors conclude the book with the return of Indian Island to the Wiyot peoples by the town of Eureka and note, “It also shows that out of the tragedy comes the promise of survivance and the power to make that promise real.” (Akins & Bauer Jr. 2022, 330) By opening and closing the book with stories about activists, the authors are highlighting the ongoing practice of tribal engagement.

This book is a welcome contribution to the growing field of California Indian Studies. It is well structured for any introductory course. The book could be strengthened with complete citations as each chapter ends with a list of sources but is not always clear. The inclusion of two maps, one with historic tribal homelands and another with current towns and cities along with reservations and rancherias illustrate California Indian diversity. The maps focus the readers attention on the meaning of place and connections between neighboring tribal nations. Akins and Bauer demonstrate that while a 1928 Congressional Act provided for a legal definition of “Indians of California” due to the Indian Land Claims Case, California Indians embraced their own definition focused on kinship, community, and connection to land.

About the Reviewer

Dr. Rose Soza War Soldier, Mountain Maidu/Cahuilla/Luiseño, is an enrolled member of Soboba Band of Luiseño Indians. She completed a BA degree in History with a double minor in Political Science and Social/Ethnic Relations at University of California, Davis and earned a Ph.D. degree in History with an emphasis in American Indian History from Arizona State University. She is a Sac State assistant professor in the Ethnic Studies Department with an emphasis in Native American Studies. Her research and teaching focus on twentieth century American Indian activism, social and cultural history, politics, education, and social justice.

0