The Book

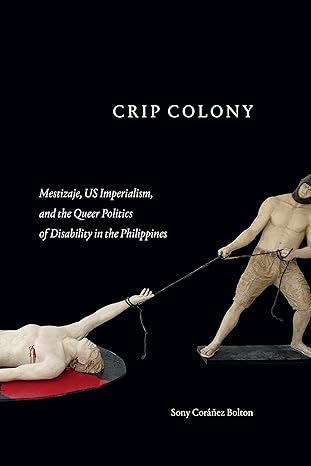

Crip Colony: Mestizaje, US Imperialism, and the Queer Politics of Disability in the Philippines

The Author(s)

Sony Coráñez Bolton

Sony Corañez Bolton’s Crip Colony is a theoretically sophisticated contribution to the current surge in Filipinx American studies scholarship that uses an intersectional disability studies framework to apprehend the transition from Spanish to U.S. colonialism in the Philippines from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries. Attending to Spanish as well as English-language literary, visual, and archival texts from the period, the book’s main argument is that both U.S. colonialism and Philippine ilustrado nationalism invoke and impose forms of intellectual (and sometimes, physical) debility that, in turn, justify their interventionist efforts at rehabilitating their lesser wards or deranged compatriots. These ideologies, policies, and practices are simultaneously racialized such that those who are deemed capable of cognitive and moral recovery through their absorptions of Spanish and/or U.S. humanisms are invariably mixed-race mestizos of Euro-American and native descent, while those who inevitably—eugenically—fall by the wayside are racialized others, including “pure” indios, Chinese, Africans and African Americans, and non-Christian “Moros.” Thus, Crip Colony not only enjoins colonial studies scholars to perceive and name “disability” as it appears in historical archives often under the guise of evolutionary notions of racial difference, but also cautions against the impulse to assert intellectual parity to counter such impositions of inferiority—an impulse that privileges the normate bodymind as the precondition of resistance and devalues physical and neuro-diversities.

The first chapter sets the stage for what Bolton alternately calls “crip colonial critique” and “queercrip” analysis by reformulating William McKinley’s infamous 1898 Benevolent Assimilation proclamation as a project of “benevolent rehabilitation.” Given the Philippine Revolution waged against Spanish rule and the declaration of Philippine independence on June 12, 1898, the U.S. exceptionalist excuse to invade and occupy the Philippines rested, according to Bolton, “on an assumption of the Filipino’s incapacity for autonomous self-rule” (48). The presumption of the “Filipinx colonial bodymind” as “too irrational and lacking the cognitive capacity to be a robust political subject” (48) but as still capable of being instructed in the arts of self-governance provides a productive frame for his close reading of the political cartoon “School Begins” (Puck, 1899). Seated alongside the newest colonial acquisitions of Hawai’i, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, in front of the recently admitted southwest states of Texas and California, and before the imperious schoolteacher Uncle Sam, the Filipino figure is visually depicted as infantilized, diminutive, and blackened, indicating his need for education under the guidance of “US tutelary imperialism” (38).

In the fourth chapter, Bolton returns to the colonial classroom and investigates reports of Muslim men in Mindanao “running amok” and slaughtering Filipinx schoolteachers in the early 1930s. Here, the seeming confirmation of Filipinx irrationality and “madness,” coupled with stereotypes of perverse Moro sexuality, not only incites U.S. administrators to redouble their exertions at “rehabilitating or even just managing these mad Indians” (139), but also compels the Philippine constabulary to control “the “unruly savage masculinity of the Moro amok” (148). The latter’s attempts to demonstrate Filipinx fitness to self-govern becomes all the more imperative in these years leading up to the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934 which granted the Philippines commonwealth status en route to full independence.

The third chapter foregrounds how such efforts on the part of the colonized to prove their quality result in the abjection of others. In an expansive reading of Teodoro Kalaw’s travel narrative Hacia la tierra del zar (Toward the Land of the Czar, 1908), a text unrecognized in anglophone-dominated Filipinx American studies, Bolton examines how Kalaw positions himself and his “entourage of Filipino mestizo statesmen” (99), including future Commonwealth President Manuel Quezon, as the rehabilitated beneficiaries of U.S. tutelage. Their capacities for national sovereignty and modern capitalist development are set against abject figures they encounter in their journey toward an international congress in St. Petersburg: namely, an impoverished Russian boy “ruined by the imperial despotism of Russia” (117) and the recipient of Quezon’s magnanimous mestizo charity; and poor, unsmiling, foot-bound Chinese girls whose “disabled” appendages prevent their “full incorporation into capitalist systems of labor exploitation” (126). Such immobile and unproductive figures contrast with Kalaw’s self-representation as “a mobile Filipino subject unfettered, unbound in space, progressively moving forward in time toward a modernity teleologically ensured by US rehabilitation” (124).

The urgency for the colonized to evidence cognitive capacity, self-discipline, societal regulation, and economic development did not appear with U.S. colonialism but was also at play during the Spanish era, as the second chapter on José Rizal’s canonical novel Noli me tangere (1886) attests. Although published prior to U.S. occupation, the novel serves as a crucial means for Bolton to elaborate on the ways that ilustrado nationalism operates through neuronormative and heteronormative mestizaje. Whereas the novel’s masculine hero Crisóstomo Ibarra embodies “the revolutionary mestizo rehabilitating society against the disablements of [Spanish] colonialism,” his former beloved María Clara, as the “bastard” offspring of a Filipino woman and a duplicitous Spanish priest, instantiates “the compromised and polluted aspects of racial mixture that come with the imposition of colonial rule” (73). Consigned at the novel’s end to a convent-cum-asylum and thus deprived of the privileges of heterosexual marriage, “mad María Clara,” as Bolton describes her, becomes “a queer figure whose mixed heritage marks a perversity that cannot be encompassed by the Filipino national project” (85).

While the disability studies approach to this historical period constitutes the book’s primary intervention, Bolton’s consistent cross-cultural and comparative racialization analyses must also be highlighted. Such connections are most vividly expounded in the introduction’s consideration of the divergent meanings of mestizaje (mixed-race status) in Latin American, Anglo-American, and Philippine contexts, but they extend to other racial formations as well. For instance, Bolton’s reading of “School Begins” carefully elucidates the racial positionalities assigned to the “Jim-Crowified African American laborer,” the “Chinese coolie,” the “Indian dunce,” and the Caribbean and Pacific figures whose visual grammars and very existence within this “classroom” have been conditioned by histories of settler colonialism, chattel slavery, Mexican incorporation, Asiatic exclusion, and Pacific imperialism (40-48). Similarly, Bolton historicizes his analysis of Moro “amoks” within its South and Southeast Asian genealogy and in dialogue with the “mad turn” in disability studies as pursued in Black studies (142-44). His reading of José Rizal’s pamphlet Filipinas dentro de cien años (The Philippines a Century Hence, 1889) in chapter one also notes that Rizal’s reference to “the despoliation of Africa” (61) by European powers does not lead to anticolonial solidarity with Black liberation movements of the time. And the institution of education makes a final, haunting appearance in the Epilogue’s mention of the discovery of unmarked graves of children buried at a Canadian Indian residential school, reminding us of the first chapter’s discussion of U.S. federal Indian boarding schools as models for Filipinx assimilation during the colonial period.

Such resonances across cultures, continents, and oceans indicate that the Philippines represents not “a narrow case study” for examining the politics of “colonial ableism” but a key node in its global manifestations (162). Bolton’s comparative race method and insistent critique of both colonial debilitations and nationalist rehabilitations enacts the kind of “ethics of solidarity” (168) he calls for in the Epilogue, refusing in the end to allow aspirations for autonomy for some to eclipse the freedom dreams of others.

About the Reviewer

Martin Joseph Ponce is an associate professor of English at The Ohio State University whose teaching and research interests focus on the intersections of critical ethnic, U.S. empire, and queer studies. He is the author of Beyond the Nation: Diasporic Filipino Literature and Queer Reading (NYU Press, 2012) and the coeditor of Samuel Steward and the Pursuit of the Erotic: Sexuality, Literature, Archives (OSU Press, 2017). His current projects include a transnational history of Asian American literature situated between contending empires, nations, and sexualities; and a comparative racial history of U.S. queer of color literatures.

0