The Book

David Weinfeld

The Author(s)

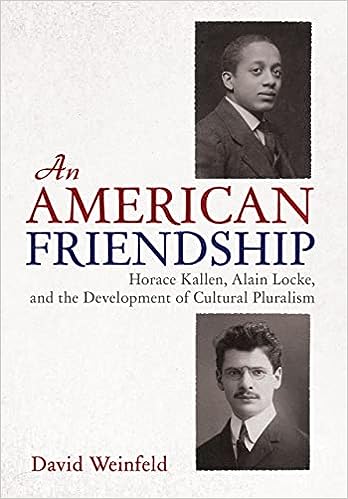

An American Friendship: Horace Kallen, Alain Locke, and the Development of Cultural Pluralism

The history of Jewish-Black relations in America is streaked with tension and filled with promise. As minorities on the margins and isolated from the mainstream, Jews and Blacks have been drawn into conflict as often as they have pulled together for common cause. Their edgy, often creative interaction has had an outsized impact on American culture, and many of its positive consequences have emerged from hard-won cross-cultural friendships between writers, philanthropists, politicians, and religious leaders. Despite many moments of distrust, Jewish-Black interaction and friendship has inspired significant progressive and radical reform throughout much of the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries.

From the alliances between progressives Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington and radicals Joel Spingarn and W.E.B. Du Bois in the 1910s and 20s to the interactions between writers Norman Mailer and James Baldwin in the 1950s and 60s and politicians Bella Abzug and Shirley Chisholm in the 1970s and 80s, Jewish-Black alliances have transformed American culture. The powerful bond between Martin Luther King and Abraham Joshua Heschel in the 1960s stands as the most potent example of such far-reaching collaborations in the past. The on-going friendships between public intellectuals Cornel West and Michael Lerner and senators Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff are examples of Black-Jewish relationships that could help reset the course of our increasingly divided nation in the 2020s. James McBride’s prize-winning autobiography about growing up in a Jewish-Black family in Harlem in the 1960s, The Color of Water: A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother (1997), adds intimate depth to a significant strain in American culture.

David Weinfeld’s crisply written, meticulously researched book, An American Friendship: Horace Kallen, Alain Locke, and the Development of Cultural Pluralism, contributes to our understanding of this inter-ethnic bond and collaborative tradition. In addition to tracing the complex, often conflicted relationship between two significant public intellectuals, from their first encounter as philosophy students at Harvard in 1906 till Locke’s death in 1954, Weinfeld explores their interactions as co-creators of a powerful, continually relevant idea. Various scholars have narrated the genesis of cultural pluralism: how inklings of this concept cropped up during a conversation in 1906 between Kallen, a twenty-four-year-old Jewish teaching assistant, and Locke, a talented twenty-one-year-old undergraduate who would go to Oxford in 1907 as the nation’s first Black Rhodes Scholar. Several have examined how Locke’s straightforward question to Kallen, “What difference does the difference make?” started a dialogue and launched a Black-Jewish friendship that shaped how many Americans understand cultural diversity into the present.

Weinfeld’s study enriches this discussion by moving far beyond the Kallen-Locke eureka moment to trace their complex relationship over the next five decades as they expanded their concept to embrace ever-wider portions of humanity and as they forged a truly equitable companionship along the way. Achieving deep friendship required transcending ingrained prejudices—anti-Semitism on Locke’s part, anti-Black racism on Kallen’s–and the odyssey toward this relationship as a symbol of cultural diversity is the overriding theme of the book. The flexible give-and-take between friends, Weinfeld argues, is “an ideal metaphor for cultural pluralism” and a more productive image for society than the tighter bonds of brotherhood and family that can “symbolize stale sameness.” “Although many other metaphors exist to describe American diversity,” he continues, “from melting pots to symphonies to salad bowls, friendship reflects a process that all individuals engaged in, even more than cooking or music” (2).

This interactive Jewish-Black relationship, Weinfeld argues, “not only led to the coining of the term cultural pluralism, it demonstrated the importance of friendship in the lived experience of cultural pluralism” (14). And he carries their story into the twenty-first century by contrasting present day multiculturalism, with its fractious tendencies, to the more integrative possibilities of Kallen’s and Locke’s writings which “remain relevant to our diverse nation and world.” “With the divisiveness of the Trump-era and the isolation and alienation brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic,” he writes, “their vision of cultural pluralism as friendship can inspire greater connectivity” in our disconnected times (208).

An American Friendship reaches this and other findings through eight succinct chapters. The first two trace Kallen’s and Locke’s backgrounds before they met at Harvard in 1907. We learn about Kallen’s impoverished childhood, growing up in a large immigrant family on Boston’s North End as the only son of an itinerant rabbi, and about his early years as a precocious scholarship boy at Harvard where, among other things, he took the same European history class as Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Locke, in contrast, grew up as a protected and watchfully tutored only child in a prosperous Philadelphia family, and he entered Harvard, in Weinfeld’s words, as one of the most “talented among the talented tenth” (40) and excelled as a brilliant but aloof undergraduate.

Chapters three and four discuss Kallen and Locke’s deepening relationship, first at Harvard and then at Oxford. We learn in detail about their earliest encounter in George Santayana’s course on Plato in Fall 1906 and the moment when Kallen as Santayana’s teaching assistant responded to Locke’s question, “What difference does the difference make?” Their friendship and appreciation of pluralism intensified from 1907 to 1908 during the academic year each spent abroad, Locke as a Rhodes scholar, Kallen on a fellowship to finish his doctorate. Weinfeld’s meticulous account of how they pulled together as outsiders encountering prejudice–how Kallen was bruised by anti-Semitism and Locke deeply hurt by anti-Black racism on the part of his fellow American Rhodes scholars and segments of British society–is a centerpiece of his book.

The final four chapters trace Kallen’s and Locke’s intersecting careers as public intellectuals from the 1910s to the early 1950s and also examine Kallen’s many reiterations of the genesis of their idea until he died in 1974. During these years, Kallen taught first at the University of Wisconsin between 1911 and 1918 and for the rest of his long career at the New School for Social Research in New York, while Locke served on the faculty at Howard University in Washington, D.C. from 1912 until his death in 1954.

Weinfeld skillfully traces many phases of their relationship through the decades. He examines how their most significant books—Kallen’s Culture and Democracy in the United States containing the first discussion in print of cultural pluralism, and Locke’s The New Negro introducing the widely influential Harlem Renaissance—were both published in 1924. He discusses how as friends they fell out of touch and were reunited at a conference organized by Locke for Black and Jewish intellectuals at Howard in 1935, a highly significant gathering described as “the first instance in which the two groups were examined together in a scholarly setting” (173). We learn how in the late 1940s, during a difficult period in Locke’s life, Kallen secured visiting teaching and lecturing positions for his friend at the University of Wisconsin and at the New School where he could expand his thought free from restraints at Howard University. We witness how they solidified their often-stressful friendship and how their concept entered public conversation by the mid-1950s only to be eclipsed by the more contentious notion of multiculturalism by the 1970s.

These are a few examples of the complex, deeply consequential Jewish-Black relationship that David Weinfeld has so carefully traced. An American Friendship is a significant contribution not only our understanding of Jewish-Black relations but also to possibilities of interactive friendship as a symbol of hope in our increasingly divided nation and world. Their vision of cultural pluralism, Weinfeld argues, “raises important questions about the promise and peril of multiculturalism.” “The legacy of their friendship,” he concludes, “offers hope in troubled times” and provides promise “for a diverse and divided United States, and for all countries where different people meet, learn, love, become friends, and contribute to the symphony of civilization” (209).

About the Reviewer

Michael C. Steiner is Professor Emeritus of American Studies at California State University, Fullerton. During his forty years at CSU-Fullerton, he taught courses and seminars on intellectual and environmental history, folk culture, the built environment, and regionalism. He won a national teaching and advising award from the American Studies Association in 2006 and was twice a Distinguished Fulbright Chair (in Hungary in 1998-99 and in Poland in 2004). He has published more than thirty peer reviewed essays and encyclopedia articles, among them prize winning essays on the significance of Frederick Jackson Turner’s sectional thesis and Walt Disney’s Frontierland. He is the author or editor of five books, most recently, Horace M. Kallen in the Heartland: The Midwestern Roots of American Pluralism (University Press of Kansas, 2020). Steiner has recently published peer-reviewed articles on “Jane Addams, Grace Abbott, and the Promise of the Cosmopolitan Neighborhood, 1907-1918,” MidAmerica 49 (2022) and “Whitewashing the Heartland,” Middle West Review 9 (Spring 2023), and he is currently completing a comprehensive study of the American origins of the idea of regionalism, The Midwestern Foundation of American Regionalism, 1890-1945.

0