The Book

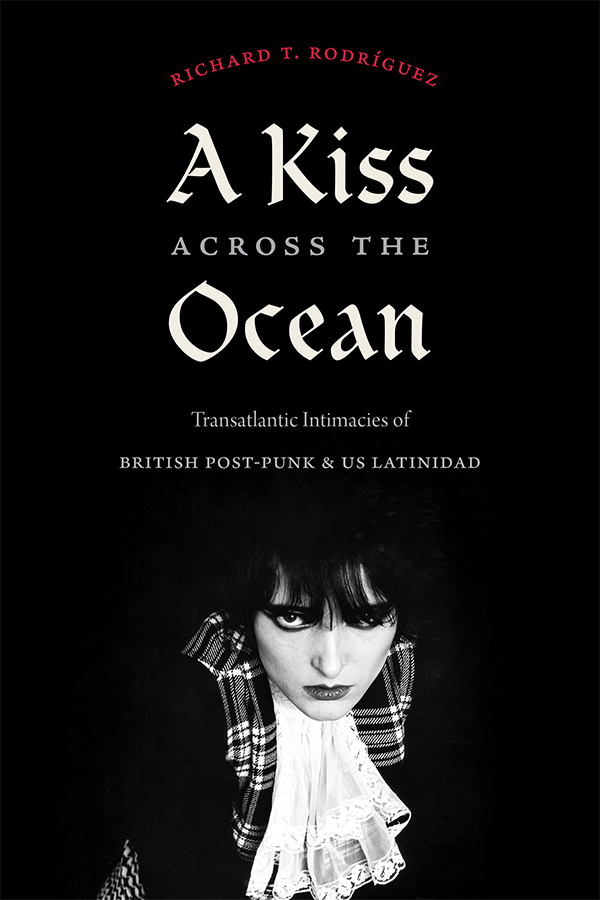

A Kiss Across the Ocean: Transatlantic Intimacies of British Post-Punk and US Latinidad

The Author(s)

Richard T. Rodriguez

Like many compelling and contemporary academic forays, A Kiss Across the Ocean… arrives at a fecund crossroad: that is, it exudes a fluid hybridity between memoir and confessional, subcultural theory and autoethnography, as well as queer/ethnic studies and fandom. In doing so, the personal and political merge into the folds of a narrative that recounts a personal journey of Richard T. Rodriguez, a Latino/x Professor of Media and Cultural Studies and English, fully immersing in idea-strewn pop music with punk antecedents. Rodriguez also exudes an evocative commitment to pushing boundaries — the work does not heap contempt on the cultural appropriation committed by white musicians but instead attempts to elucidate their well-meaning hybridity: the give and take of cultures; the listening, sharing, borrowing, and becoming; the shared intimacies and reciprocities, however fleeting and imperfect.

Rodriguez’s fluid and in-depth rigor does not simply explore/map the craft, style, and tropes of Pet Shop Boys or Culture Club from his own matrix of gender, sexuality, class, region, and ethnicity. Instead, he painstakingly points out the interzones between post-punk adherents, from U.K. performers to mostly California fan milieus (record shops, nightclubs, malls, high schools, homes), specifically the neighborhoods of marginalized, scapegoated, and suppressed communities of color with Latino backgrounds. In essence, you will not witness exposes of German (Xmal Deutschland) or Swiss (LiliPUT) post-punks, or much stateside fandom outside of Los Angeles.

The relationships between fan and artist, between consumer and maker, between critic and writer, even informal and formal archiving, will always be slippery and unfixed, relational and transactional. Rodriquez travels these byways, looking at how people like Morrissey of the Smiths not only appeals to Latinx fanbases but has become woven into a kind of relationship, across time and space (essentially a kind of trans-locality), via networks and formats, of purportedly haptic qualities — energies made physical — emerging through affinity. And this book, Rodriguez notes, functions as a kind of mix-tape, blurring time past and present, chronologies and temporalities, as well as feelings, memories, and discourse.

Luckily, Rodriguez is not interested in policing genres too heavily, creating rigid barriers of inclusion, or compulsively chasing authenticity. Post-punk is not solely about strict dates, band bios, lyrical allusions, and instrumentation, like a jagged guitar riff, ghostly and willowy vocal strain, or quasi dub-style rhythm. Broadly, his lens surveys the schisms that occurred post-Sex Pistols and examines a loose-knit group of peers that shook up the norms (whether the music industry and pop culture). These bands often reflected the ghost presence and holdover tenets of punk within a poppier cocoon, shaping subversive sensibilities but losing punk’s guitar-bolted “rockest” vibe and direction.

In a refreshing tactic, at the end of the book, Rodriguez explores a limited number of post-punk “cover bands,” often the subject of disdain, to illuminate how they serve as avatars rerouting beloved music, navigating it in meaningful ways for ever-shifting communities, like inner city Latinx, who desire to unlock their identities in ways that outsiders will find surprising and relevant. That is, for every successive generation, such bands re-circulate post-punk, letting the effects of the music commingle with communities in newfangled ways.

However, some readers will be baffled and raise their eyebrows, for myriad reasons. For one, the usual suspects of post-punk are missing in action: gone are the Fall, Gang of Four, even Raincoats, each groomed over the years by critics as models of the genre. Instead, Rodriguez replaces them with bands most writers might more squarely align with the Blitz/New Romantic movement, the pop-edge of the continuum, including Soft Cell and Blue Rondo à la Turk, the latter who were once met with derision by iconic punk writer Jon Savage. This also means that the catalog of intellectuals usually associated with post-punk are absent as well: Derrida, Foucault, Baudrillard, Debord, Barthes, etc. Instead, Rodriguez leans into a more contemporary field, whether journalist Stuart Cosgrove or gender/queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick.

Next, many Do-it-Yourself strain of post-punk fanzines with punk pedigrees are absent too. In contrast, Rodriguez leans into quotable mass-marketed fare, glossies and magazines like Smash Hits, whose circulation grew from 500,000 to 1 million throughout the 1980s, commoditizing post-punk desire as part of a corporation’s profit enterprise. However, the tension between art and marketing does powerfully underscore the chapter, “Mexican Americos,” a finely-webbed critique of the “carnage” and “carnality” (139) seesawing in the works of Frankie Goes to Hollywood in addition to the subsequent solo career of singer Holly Johnson.

This portion not only addresses the Cold War machinations and vexing doom psychology of the era but also addresses the queer frisson within pop’s milieu, like the barbs traded between members of Frankie Goes to Hollywood and Boy George, but also the role of management, media campaigns and promotional affairs, including a hefty dose of tawdry double entendre (“All nice boys love sea men”) in adverts used to “sell” Frankie product. HIV/AIDS are mentioned in passing, as well as Ronald Reagan’s Immigration Reform and Control Act, which dealt with the legalization of previously undocumented workers. This chapter effectively places its spy-glass on queer sexual revolt at a time when closeted gay performers like Boy George, Michael Stipe of REM, and even punks like Bob Mould and Grant Hart in Husker Du, evaded the conversation. It also illuminates how artists dealt with the hype machine versus their artistic goals, aesthetics, and politics, which feels ever-relevant in a time of increased queer phobia, including book bans, ever-present hate speech, and attacks on Drag Queen Story Hour, even in places such as New York City.

Next, little is explored about material culture, the making of clothes and fan ephemera, though his chapter on zoot suits dives into the dynamics of secondhand knowledge, the circulation of goods that are “remade and remodeled” (107), thus resemble and embody a “long standing ability to buck normative gender codes and temporal configurations” (111). And though the chapter includes American acts like Kid Creole and the Coconuts, he misses an opportunity to explore how those same zoot suits were deployed in the 1990s by bands that were far less gender subversive, like Cherry Poppin’ Daddies and Royal Crown Revue, featuring members of the anthemic hardcore band Youth Brigade. Such an acknowledgement of differences, code switching, or contrast, could have been useful, since the chapter seeks to show that, despite differences in meaning and context, “youth on both sides of the Atlantic were similarly drawing from a decades-earlier shared sense of style” (114). Still, the chapter does dissect the curious post-punk melange of Blue Rondo à la Turk with aplomb, who reflect and embody larger shifts within British subcultures at-large regarding a complex fascination with Latinidad culture.

The chapter exploring Marc Almond of Soft Cell, which also loops in pioneering gay writer John Rechy, examines Almond’s interviews and lyrics, his sometimes-clumsy handling of ethnicity, and the psychogeography of his time spent in Manhattan, including disappearing Times Square haunts, neighborhood drag clubs, and encounters with street toughs. In doing so, Rodriquez’s balancing act is crucial and visible — he is both enamored with the artist’s oeuvre but uncomfortable with Almond’s occasional verbal and written pitfalls and racial blindsides. Nonetheless, Rodriguez underscores the transatlantic intimacies between Almond and Latinidad, however marred and imperfect.

Punk is understood as a revolt rooted in the vulgar body and contagious body politic – phlegm, puke, and profanity; fanzines brainstormed in public bathrooms; taboo items like bondage pants and gay cowboy shirts worn brazenly; swastika armbands and trash bags used as ‘fashion’; and spray-painted jackets stenciled with Hate and War … all meant to be an affront to public manners and good taste. This means the layered and implicit queerness of Pet Shop Boys is a far cry from punk queerdom, including the abrasive din of the Dicks, whose out-and-proud guttural singer Gary Floyd, a country boy from Palestine, TX, bellowed “Shit on Me,” “Little Boys’ Feet,” and “Saturday Night at the Bookstore” (about glory holes). Hence, Pet Shop Boys might seem entirely manufactured in comparison. Fortunately, the sexual politics of queer synth bands is mentioned, like Bronski Beat, who adorned their LP art with a pink triangle and advocated for lowering the age of consent. Contrasting punk and post-punk approaches could have made the presence of queer revolt more inclusive, dynamic, and set in relief.

None of this should distract from the boldness of the text, its tenderness as well, and its scope of intellect. But despite the textual analysis and historic truth-telling, one may hunger for actual conversations and interviews with the actual artists, interposed with the ruminations and theory-building, which would make this less fanboyish. Rodriguez chooses to talk to other fans, colleagues, and academics rather than engaging artists (in full view of the reader) directly about their lyrical content, ever-changing musical drift and reinvention, moral core and belief systems, and their understanding of markets and business — the art of entertainment.

About the Reviewer

David A. Ensminger is a college instructor and the author of books covering both American roots music and punk rock history—Visual Vitriol: The Street Art and Subcultures of the Punk and Hardcore Generation (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2011), Mojo Hand: The Life and Music of Lightnin’ Hopkins (Univ. of Texas Press, 2013), Left of the Dial: Conversations with Punk Icons (PM Press, 2013), Mavericks of Sound: Conversations with the Artists Who Shaped Indie and Roots Music (Rowman and Littlefield, 2014), The Politics of Punk, and Out of the Basement: From Cheap Trick to DIY Punk in Rockford, IL, 1973-2005 (Microcosm, 2017). His book Roots Punk: An Oral History will be published in Nov. 2023 by Univ. Press of Mississippi, and in 2024 the second edition of Punk Women will be released by Microcosm Press. Both The Boston Globe and The Economist have highlighted his research; meanwhile, he writes for publications like Art in Print, The Journal of Popular Music Studies, Houston Press, Trust (Germany), Artcore (Britain), Razorcake, and Maximum Rock’n’Roll.

0