I went to high school in central California in the 1980s. My sophomore English class was formative, foundational. I had a brusque, gruff, outstanding teacher who taught me more about the mechanics of writing in one year of high school than I’ve learned in all my years since. And she walked us—or, really, marched us—through American letters from (roughly) Washington Irving to Chaim Potok, while also teaching units on such things as analyzing poetry or interpreting fiction and, every Friday, giving a spelling / vocabulary test.

Somehow, our teacher mostly succeeded in getting us to do the reading and talk about the texts. We had a survey textbook—gosh, I wish for the life of me I could remember which publisher’s it was; I’d love to page through it now—and we read a few standalone novels throughout the semester: The Scarlet Letter, Turn of the Screw, The Great Gatsby, and My Name is Asher Lev.

I don’t recall how far the survey textbook went in terms of coverage of American authors. Was there a Ray Bradbury story in it, perhaps? Was Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” in our anthology? Poetry by Robert Lowell? Sylvia Plath? I honestly don’t know.

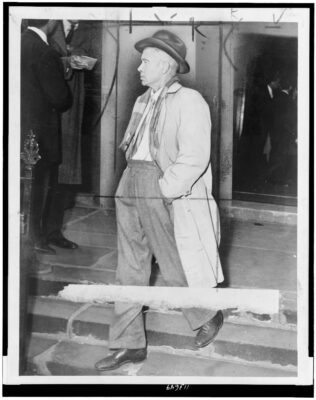

E.E. Cummings, 1953 (Library of Congress)

I do recall that there apparently wasn’t enough E.E. Cummings in the textbook to suit the high school English department; we all got a mimeographed collection of Cummings poems to read, and we did a whole unit on Cummings as an exemplar (the exemplar?) of modern American poetry. We spent a fair amount of time on Cummings—maybe three weeks?—and had to write a paper analyzing how the formal aspects of his poems reinforced his idiosyncratic figurative language to communicate meaning. Something like that. It was a major assignment, a big deal for our semester grade: making sense of the formal and figurative rebellions of E.E. Cummings.

I was reminded of this unit of study recently while reading a chapter in Louis Menand’s The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War. It was his chapter on literary criticism, “The Free Play of the Mind.” He had written extensively about the Beat writers earlier in the book, in a chapter that mostly explored Ginsberg’s connections to and frustrations with Lionel Trilling. But I wasn’t surprised to see Ginsberg and Kerouac again, this time mixed in with I.A. Richards and Northrop Frye and Robert Penn Warren. In these big books about major eras or turning points of American thought, no matter who writes them, there’s usually a cast of recurring characters; and for the field of American studies more broadly (and let’s put Menand in that pasture for now), there is sort of a collective thesaurus of texts, key figures, key thinkers, key moments scholars call up as needed to convey the sense of an era. So it is with Menand’s massive book—and all for the good.

Anyway, as I was thinking about our collective cast of characters for sweeping surveys of American thought and culture, and thinking about how early in my life I encountered some of these standard figures and how recently I encountered others, I realized that in all my reading of American cultural and intellectual history, I have almost never encountered E.E. Cummings as a significant figure in anybody’s history.

I’m not saying that I should be seeing numerous mentions of E.E. Cummings in works on American thought and culture in the 20th century, whether that’s the Progressive era or the Depression or the war years or the Cold War. I’m not saying that I find the paucity of mentions problematic. But I’m intrigued by the fact that Cummings is probably the only American writer I was assigned to read extensively who doesn’t figure into many histories of his era. He loomed way too large in that high school curriculum—we read more of Cummings than we read of T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, or even Robert Frost—but he really hasn’t showed up much for me since. As I said on Twitter, “I was led to believe that there would be a great deal of E.E. Cummings content to grapple with throughout adulthood and there really is not much.”

The easiest move here is to say that nobody drags E.E. Cummings into their story because his work just wasn’t that important, it wasn’t that resonant in the culture; whatever representative ideas may be salient in his poetry are just as salient in the work of more interesting and more important thinkers. Even if one’s object of inquiry is “middlebrow culture” or “religious sensibilities and American poetry” or “Harvard in the early 20th century,” there’s no need to use Cummings to carry the narrative load. I am not out here asking for more E.E. Cummings content, and I doubt I’ll be providing any beyond this blog post.

What’s a bit more interesting is to think about what function E.E. Cummings served in the high school English classrooms of the 1980s, since he seems to serve very little function as a significant node of thought in American intellectual history. And here I think Menand—or Robert Genter in his fantastic study Late Modernism: Art, Culture, and Politics in Cold War America, or Jamie Cohen-Cole in his marvelous book The Open Mind: Cold War Politics and the Sciences of Human Nature—can help answer the question. They do this by reminding us of what the stakes were for art during the Cold War, what the possibilities for art—for painting, for music, for poetry, all of it, any of it—became during the Cold War. They remind us how urgent it was to irresistibly shape young minds to believe in freedom as both imperiled and irresistible.

To put it bluntly, E.E. Cummings was a very safe choice to serve as the prime example of an artist who challenges formal conventions, who rebels against tradition, who does something aesthetically exciting and new in the name of individual freedom of expression. Teaching Cummings’s break from formalism was a way of gesturing toward and valorizing artistic courage—and individuality, and creativity, and anti-Totalitarian nonconformity, and all those other Cold War desiderata—without putting any Cold War pieties at risk.

It was almost an inoculation, to have all of us grapple with Cummings as the standard-bearer of aesthetic rebellion. That wild and wacky Cummings with his peculiar diction and his daring break with the conventions of capitalization, punctuation, and stanza structure! Talk about a rebel without a cause.

But it’s not as if they were going to have us read excerpts from “Howl” or On the Road. At least E.E. Cummings was something—something very safe. And it makes good pedagogical sense, if you’re telling a story about American poetry as a move from traditional verse to free verse, to use Cummings as an example of what this break for freedom looked like. The formal challenge to poetic convention is something students can easily see on the page, even if they struggle to make sense of it. Asking a bunch of high school students to take a deep dive (as deep as we could) into Cummings’s artistic choices where nothing much was actually at stake was a roundabout way of telling us, It’s okay to rebel when this is what rebellion entails.

That’s probably what My Name Is Asher Lev was doing in the curriculum as well—that, and doing some work for the idea of “Judeo-Christian” America, and perhaps counting as a required “ethnic literature” reading. Don’t get me wrong: I’m very grateful that we read that novel; it provided me with a way to imagine what it might feel like to have to choose between being true to one’s upbringing and one’s faith and being true to oneself and one’s art. Assigning that novel was a way of affirming and reinforcing the ideals of liberal secular pluralism, the ideals of Cold War America, by presenting such affirmation as something hard-won through rebellion. And if that novel checked off a box for “ethnic literature,” it was a much safer text to discuss than, say, James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain.

I am not suggesting that my high school English teachers—bless them all—or your high school English teachers sat down and said to themselves, “What should we have these kids read that will feel very daring and edgy for them but won’t lead any of them into actual trouble or make any trouble for us.” Indeed, I know my own teachers were very conscientious about opening our minds and enlarging our experiences.

But, again, recall Jamie Cohen-Cole’s study of The Open Mind—developing the “open-minded” citizen who was at the same time able to resist the siren song of Totalitarianism was the Cold War mission of social scientists and educational reformers, a mission that certainly continued into and through the 1980s. How to encourage high schoolers to resist groupthink; to value independence of mind, creativity of expression; to challenge reified conventions; to champion freedom of thought without falling prey to “anti-American” thought—how to encourage high schoolers to make a break for freedom without actually breaking anything? Have them analyze the work of E.E. Cummings.

Still, there’s no such thing as a safe or harmless call to freedom. Along with Potok’s My Name Is Asher Lev, a poem by Cummings, assigned to me in high school, became one small stepping stone on my crooked, painful, hard-fought path away from evangelical dispensationalist fundamentalism. Here it is; I’m sure you know it:

no time ago

or else a life

walking in the dark

i met christ

jesus)my heart

flopped over

and lay still

while he passed(as

close as i’m to you

yes closer

made of nothing

except loneliness

Upon my parochial mental horizons, those lines from my sturdy and conventional Cold War education landed like angelic bombs.

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’m guessing that several other things helped make Cummings safe for consumption: pedigree (Harvard, and father a professor there, New England-born), religion (Unitarian), ethnicity (“white”), and gender (male). The odds of Cummings not being favored and not benefiting from his privileged background were slim to none. He was also, according to his own writings, conservative, a Republican, and later (apparently) a supporter of Joseph McCarthy. Putting all of this on the table, it’s easy to see why he was safe for English teachers during the Cold War. – TL

PS: It is true that his 1930s work, Eimi, exposed Stalinism to the world. But he also never apparently softened his anti-communism in any way.

Yup. Cummings was really a paragon of conventional respectability. Again, that makes his experiments with form and diction a little bit easier to parse as purely aesthetic innovations rather than as expressions of or responses to any broader cultural restlessness. That doesn’t mean his poetry isn’t good or worthy of attention; I enjoyed it and still do. But he can fill a slot in the curriculum that “covers” and simplifies several decades of significant developments in poesis and poetic theory. He and Robert Frost made a good pair–widely-read, much loved poets who could roughly illustrate a binary of formalism and free verse. No harm in reading either of them–but not much danger either. Amy Lowell and Robert Lowell would have been more risky.

I’m not sure if Cummings’s politics on their own make him an undesirable subject for American intellectual historians, or if it’s just that his politics (and his poetic themes) made him unlikely to be visible in the kinds of debates and cultural conflicts that are of interest. But if you were looking for a figure who symbolized change and newness while actually upholding continuity and sameness, you could do worse than Cummings.

Hi there! Thanks for this reply. Sorry for my tardiness in acknowledging it. I agree with on all points—paragon, worthy of attention, no harms or dangers inherent in reading, upholding continuity and offering some change, etc.

When it comes to poetry-introduced-high-school, I was more of a Frost guy inasmuch as I attended. I wish I had been introduced to a wider range of authors and topics. Then again, poetry wasn’t really my bag as a high schooler and I probably would’ve ignored it, or made fun of it as “sissy.” Yes, I was an @$$-hole at that stage of my life. I also cared nothing for great books, classics, or being told much of anything. Teenage pride and toxic masculinity were all around. My outlook was “parochial” and limited for different reasons.

Again, thanks for bringing this discussion here. Anything taught widely in our high schools for any period of time is, to me, worthy of the time and energy of intellectual historians. – TL

I don’t have much (or anything really at the moment) to say about Cummings, but I found Menand’s book frustrating; while I glanced ahead to the end, in terms of actually reading it I stopped at around p. 400. Despite what he claims in the preface, there seemed to me to be no unifying theme of much substance, which means that the choices about whom to include and whom to exclude felt somewhat arbitrary. And there’s no real thesis or argument. The only throughlines seemed to be the contested and varied meanings of “freedom,” and to a lesser extent cultural interchange especially (though not only) between the U.S. and France, and neither of those seemed justification enough for a book of this length.

I address this question in my Reviews in American History article about Menand’s, The Free World: https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/896949