The Book

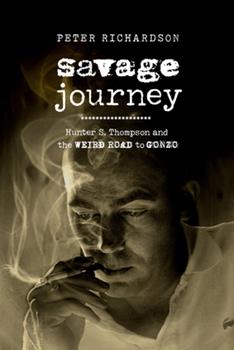

Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo

The Author(s)

Peter Richardson

It has been said that Hunter S. Thompson is the favorite writer of those who do not like to read.[1] Why is this? Most likely because of the purported lifestyle of drugs, guns, violence, and mayhem which surrounds his persona. While Peter Richardson acknowledges this in his biography of Hunter S. Thompson, Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo, Richardson does not make these things the focus of his biography. Instead, he wants Thompson to be taken seriously as a writer. Richardson chooses to focus on Thompson’s growth and development as a writer, and the subsequent self-imposed obstacles he faced after he became more of a public figure. He also discusses Thompson’s legacy and legitimacy as a key contributor to 20th century American letters.

Artfully crafted and dutifully researched, Richardson sees Thompson’s oeuvre as the pursuit of the American Dream. He sees how it had its foundations in Horatio Alger to Thompson. The rise from rags to riches, to make good in America, was a certain mindset for Thompson.[2] Richardson argues that Thompson searched for this throughout both his writing and his life. Yet, the particular American Dream he was pursuing was more so intangible and fleeting than the white picket fence and the two-car garage. Richardson believes Thompson equated the American Dream to Freedom–a freedom that would allow him to live by his own rules.[3] In attempting to do so, he encouraged others to do the same. Thompson was not encouraging anarchy, rather the opposite. It was a more libertarian pursuit of the free connection of ideas and actions which allowed each person to be responsible for his own self, thus aiming toward a greater good. In contrast, he saw men like Richard Nixon, capitalize on what they believed was the American Dream and manipulate it for their own greedy benefit. Such thinking ensured people could be conned in believing in what the establishment had to offer.[4]

Nixon proved a worthy adversary to Thompson, and Richardson goes so far to see him as Thompson’s muse. In fact, he believes that one of the reasons that the quality of Thompson’s work declined after Watergate, was because he did not have Nixon around anymore[5]. Richardson devotes chapters to Thompson’s interactions with and feelings of Nixon. He believes that Nixon was Thompson’s muse and once he resigned the presidency that there was not the same ferocity in Thompson. He carries this line of thinking toward the end of the book when he presents Thompson’s eulogy of Nixon for Rolling Stone. Here, Thompson is at the height of his powers again, as he is fully invested in setting the record straight for history to regard Richard Milhouse Nixon. Richardson credits Thompson for his astute political mind.[6] From his campaign as County Sheriff for the Freak Power Ticket to bringing to light the right-wing attitudes that Nixon had encouraged that were later expanded on by Presidents Regan and Trump, Richardson sees this as part of Thompson’s legacy.

In presenting what should be considered his legacy, Richardson divides the book up into twelve chapters. They serve to work as more than just highlights of Thompson’s life and career, but as building blocks that helped shape himself as a writer and then continuing to live off of that reputation and then construct a lasting legacy worthy of critical study.

The book traces Thompson’s beginnings as a child in Kentucky to his time in the Air Force, to the beginnings of his life as a professional writer, to the role that San Francisco played in nurturing Thompson as a writer, as well as Thompson’s experiences at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. Richardson believes these are among the four major points in Thompson finding his voice and becoming the voice of Gonzo Journalism.[7]

Thompson’s work for Scanlan’s, Ramparts, and Rolling Stone was instrumental in allowing him to move beyond the objective role of the journalist to the more subjective writer who emerged as a key figure of Gonzo Journalism.

Thompson’s paring with Ralph Steadman was seen as key to help Thompson visualize his work, especially the “Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Furthermore, Richardson sees those two works along with Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail 1972 as the major works of Thompson.[8]

Lastly, Thompsons’s choice to write in the voice of Raoul Duke is shown its importance as it helped create its own style and genre.[9]

Throughout Savage Journey, Richardson demonstrates how Thompson was a unique voice but one that did not work in isolation. He presents information and anecdotes from colleagues and scholars to illustrate Thompson’s development as a writer. While many critics see Thompson as directly influenced by Jack Kerouac, Richardson argues that Thompson was more influenced by Henry Miller, in regards to how he approached his work more so, than what he wrote about.[10] Richardson also sees Thompson’s literary heritage in line with Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, and H.L. Menken.[11]

Savage Journey moves beyond the spectacle that was Hunter S. Thompson and focuses on his significance in American letters. It is a solid bridge between the writings of Hunter S. Thompson and the persona that was created to embody the spirit of Gonzo journalism.

[1] William McKeen as found in Peter Richardson Savage Journey: Hunter S. Thompson and the Weird Road to Gonzo (Oakland: University of California Press, 2022), 4.

[2] Peter Richardson, Savage Journey, 8.

[3] Richardson, Savage Journey, 8 – 9.

[4] Richardson, Savage Journey, 23 – 24.

[5] Richardson, Savage Journey, 178.

[6] Richardson, Savage Journey, 187 – 188.

[7] Richardson, Savage Journey, 206-207.

[8] Richardson, Savage Journey, 207.

[9] Richardson, Savage Journey,207-208.

[10] Richardson, Savage Journey, 205.

[11] Richardson, Savage Journey, 209.

About the Reviewer

Jody Spedaliere PhD (Indiana University of Pennsylvania) is an Instructor of English at Pennsylvania Western University’s California Campus. He is also an adjunct faculty member at the University of Pittsburgh at Greensburg and the American Public University System. He is the author of two works of literary study, The First Post-Modernist Poets – Edgar Allan Poe and Emily Dickinson: A New Way of Reading Classic Texts (2017, the Edwin Mellen Press), and The Construction of Fiction Through Personal Experience in the Work of William Saroyan and Jack Kerouac: The Autobiographical Components of Literary Experience (2018, the Edwin

Mellen Press).

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

During my sophomore year of college (1973-74) an article written by my political science professor (who was considered a “hippie” at my conservative Catholic school) appeared in the college newspaper. It claimed that the professor and Hunter S. Thompson had spent Saturday drinking and discussing current affairs in the pit of the student union until they were ejected by a campus security officer who did not believe that Thompson was really a well-known author of countless articles and three books. That was the first time I’d ever heard of Thompson. I quickly asked the professor if the article was true; his response: “No, it was gonzo!” Apparently the exercise was either a joke, a challenge, or a sly device for introducing Thompson to students at that particular college—which said professor believed to be intellectually sheltered and socially, culturally, and politically challenged. It worked in my case; I soon purchased and read Hell’s Angels, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and (in the immediate wake of the McGovern wipeout) Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72. Strangely, some of my friends from my Connecticut hometown found their way to Thompson independently (yes, including some guys who didn’t read much). I don’t have the space here to expand on this, but Thompson was one of those writers who personified a certain transient spirit of a brief, tumultuous time period. I look forward to reading this biography of him.