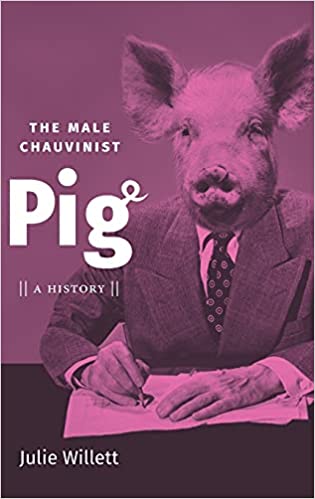

The Book

The Male Chauvinist Pig: A History

The Author(s)

Julie Willett

Over the last decade, scholarship revisiting the second wave of feminist activism has exploded. Julie Willett’s book, The Male Chauvinist Pig: A History, makes an especially unique contribution to that scholarship. Equal parts cultural, political, and affective history, the book examines the contours of the male chauvinist pig as an insult and a cultural icon, as a personality trait and an instrument of power from its beginnings in second wave feminism to its most recent and powerful incarnation in forty-fifth U.S. President Donald J. Trump. Central to Willett’s analysis is an exploration of the complex relationship between humor and power. She shows that “A joke is never just a joke, but a visceral force to be reckoned with” (108). One of the book’s central tensions is its recognition that to analyze the relationship of humor to power is to take the fun out of it. In a sense, Willett consciously adopts the position Sarah Ahmed has called the feminist killjoy, a figure whose feminism obstructs the joy of others.[1]

Humor is messy. It can be fun, exuberant, offensive, and volatile, sometimes all at the same time. It can be deployed to mock, to critique, to attack, to redeem, to enlighten, and to connect; it is always a conduit of power. Willett’s analysis of the male chauvinist pig examines these multiple functions of humor, primarily by turning the “great man” approach to history on its head, examining the “perverse appeal” (128) of the great men of chauvinist pigdom. Looking at such cultural icons as tennis great Bobby Riggs, loser of the infamous “battle of the sexes” tennis match to Billie Jean King, Playboy founder Hugh Heffner, talk show personality Rush Limbaugh, and Donald Trump, Willett examines the political landscapes in which male chauvinist pigs have disguised misogynist humor as just plain fun. This allows them to characterize their feminist anti-heroes are all-too-serious killjoys who can’t take a joke. Too often, the popularity of pig humor has also obscured, eclipsed, and sometimes erased feminist comedy, marking (pissing on?) “funny” as a male prerogative. Women then appear as the butt of the joke, but rarely the origin of it.

Willett shows how Bobby Riggs’s humor “most profoundly shaped the collective memory of the match in ways King’s did not” (19). King, for example, gifted Riggs a piglet she had named Robert Larimore Riggs before the match, indicating Bobby Riggs’s male chauvinism. Early male chauvinist pig extraordinaire Hugh Hefner, founder of the Playboy franchise, mainstreamed comedy as the chauvinist pig’s brand. Both of these pigs’ strategies marked their feminist opponents as dowdy, stoic, and too serious to take a joke, and comedy came to serve the cultural and gender politics of male chauvinism.

Especially in the early 1970s, the political humor of the male chauvinist pig began to lean conservative, juxtaposing itself to the dowdy, feminist, and feminized American left. By the early 1990s, pig humor and the pig persona was proudly embraced and deployed by conservatives, most acutely by radio personality Rush Limbaugh and later by Donald Trump. Limbaugh capitalized on the “feminazi,” linking feminism with authoritarianism and especially with humorlessness. He and other right-leaning public figures showed themselves to be cooler and funnier than either their conservative predecessors or the out-of-touch limousine liberal squares on the American left. At least for Americans interested in pleasure, this shift marked the political left and feminism in particular as much more a political threat than male chauvinism. It was the man-hating humorless feminist killjoys who needed to be held at arms-length, not fun-loving, funny, harmless male chauvinist pigs. This claim, for Willett, made Limbaugh’s and later Trump’s objectionable speech into humor that liberal and feminist stooges simply needed to get over. More disturbingly, it also made feminism’s demands for change, however humorously they might be framed, into imperatives for women to simply lighten up.

Willett shows how at the same time this new breed of male chauvinist pigs opened new directions for feminist humor, first embodied by Texas democrat Ann Richards who famously quipped that George H.W. Bush “was born with a silver foot in his mouth” (quoted on 110) and later embraced by nasty women and pussies that grab back. Willett juxtaposes this feminist humor with the humorlessness of male chauvinist pigs when the joke is on them. This is perhaps best exemplified by Donald Trump’s inability to take a joke, from his twitter-raging at a Saturday Night Live skit mocking his predilection to tweet to his refusal to attend the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, a staple of American culture that has featured a comedic roast of the president since 1983.

Willett concludes that “Perhaps the gravest problem with the old-school battle of the sexes is that it relies on humor to lighten the heavy issues of oppression, serving all to tragically to mask hate speech as just a joke” (128). While hate speech is never just a joke, Willett’s framing, here and at throughout the book, sets up humor and hate speech as binarily opposed, suggesting that hate speech masquerades as but is not humor. I wonder if this configuration may cover over a much more sobering possibility that hate speech and humor may not be categorically opposed, that objectionable speech can also be funny. Indeed, it may be that the very claim that humor and hate are mutually exclusive categories covers over the most dangerous potential of humor, which is not merely to lighten the load of oppression, but to make hate itself fun and funny. That is, Willett’s analysis of the disturbing elements of pig humor goes far into the belly of the beast, but perhaps doesn’t take the final step.

[1] See Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

About the Reviewer

Christine Talbot is Associate Professor and Program Coordinator of the Gender Studies Program at the University of Northern Colorado. Her areas of interest are Women’s and Gender Studies, Feminist and Queer Theories, U.S. History, U.S. Women’s and Gender History, History of Sexuality, Mormon Studies. She is author of A Foreign Kingdom: Mormons and Polygamy in American Political Culture, 1852-1890, University of Illinois Press, 2013, “Mormons, Gender, and the New Commercial Entertainments,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, July 2017, “Constructing a National Marital and Sexual Culture: Reconsidering the ‘Twin Relics of Barbarism,” in Reconstruction in Mormon America, edited by Brian Q. Cannon and Clyde A. Milner II, University of Oklahoma Press, 2019. Her book Sonia Johnson: Mormon Housewife Turned Radical Feminist is forthcoming by the University of Illinois Press.

0