The Book

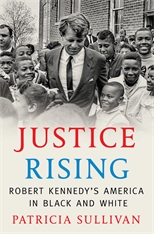

Justice Rising: Robert Kennedy’s America in Black and White

The Author(s)

Patricia Sullivan

Patricia Sullivan’s Justice Rising traces Robert F. Kennedy’s deepening engagement with America’s racial challenges from the 1960 campaign until his assassination in 1968. This ground—Kennedys, civil rights, urban crisis, the Sixties—is among the most thoroughly covered in all American history. Yet Sullivan demonstrates that there is still more to learn when an experienced historian works with a narrower focus from an exceptionally strong foundation in the sources.

Kennedy is among the most lionized American figures of the 1960s. He demands close historical scrutiny. But the relevant primary and secondary sources to master are vast. Sullivan still faced this daunting challenge, even with a narrower focus. However, the remarkable number of oral history and published reminiscences about Kennedy surely compensated some for this heavy work. In the end, Sullivan affirms the high regard in which his compatriots and many historians hold him. She makes clear that Kennedy, both as Attorney General and later as a U.S. senator, mostly responded to developments set in motion by others–African American activists and their opponents. To his credit, he did not denounce the activists or try to sidestep or politically finesse the challenges. Instead, he took the people and the implications of the Freedom Rides, integrating Ole Miss, Selma, the Watts riots, and Mississippi Delta and inner city poverty seriously. He engaged with the people and the issues and, more important, remained engaged with them. The centrality of the activists in driving events forward often required Sullivan to give them nearly as much attention as Kennedy. Her narrative thus cuts back and forth between the Department of Justice and the Senate and the often very dangerous grassroots. Kennedy himself and the talented, committed Americans he recruited to his side make for helpful historical protagonists. They repeatedly went out into America to be with these people, to talk with them, to see for themselves. The result is a fine-grained, compelling study of Kennedy evolving as a leader through his engagement with the deeply intertwined issues of civil rights, the urban crisis, and poverty.

RFK believed that reconciling the races to do better by African Americans and poor people generally was the major issue confronting the United States in the 1960s—the problem that had to be solved if Americans were to become better versions of themselves and create a better America. Kennedy’s focus on improving race relations, Sullivan shows, led directly to his engagement with economic inequality and poverty: “Kennedy was a rare person in the upper echelons of political power and influence: one who, over a stretch of years, had personally seen and experienced the reality of life in America’s poorest communities. He viewed indifference, fear, and prejudice as the greatest obstacles to change—along with the public figures who played on those fears.”[1] Sullivan carefully charts RFK’s relations with African American leaders, particularly Martin Luther King, Jr. She shows how the two men slowly came first to respect one another, ultimately to admire each other, and finally to work together on behalf of the most disadvantaged Americans with RFK supplying King the germ of the idea that became the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968.

Reading about Robert F. Kennedy in 2023 is a painful reminder that we live neither in spring 1968 nor that moment that briefly seemed to augur the fulfillment of RFK’s vision, Barack Obama’s November 2008 election. Rather, Sullivan’s RFK reminds us how far away that goal remains. Sullivan calls attention to three kinds of courage in Kennedy that remain rare in public life. The first one was physical courage. RFK seems to have never ducked a difficult or dangerous encounter, sensing always that the positive way forward started with personal connection. The second was moral courage. Drawing on a remarkable capacity for empathy, he readily grasped the right thing to do and did it, regardless of the difficulty. Third, and perhaps most striking to us today, he had the courage to pursue solutions to difficult problems through collective effort. Rather than just make a show of trying, RFK acted on his conviction that difficult problems could be solved if good, talented people came together, rolled up their sleeves, dove into the complexity and challenge—and then stuck with it to make it happen. RFK was not alone in possessing this last form of courage, more common among mid-twentieth century Americans than Americans today. Sullivan suggests that these forms of courage revealed RFK’s authenticity, the source perhaps of his charismatic appeal. She quotes local California activist Herbert Lopez, who called RFK “the last of the great believables.”[2] Sullivan’s book begs the question of whether RFK was both the first and the last of his kind.

[1] Patricia Sullivan, Justice Rising: Robert Kennedy’s America in Black and White (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2021), 352.

[2] Sullivan, Justice Rising, 436.

About the Reviewer

Tom McCarthy is professor and chair of the History Department at the U.S. Naval Academy. He holds an MBA from Columbia and a PhD in history from Yale. He is the author of Developing the Whole Person: A Practitioner’s Tale of Counseling, College, and the American Promise (Peter Lang, 2018) and Auto Mania: Cars, Consumers, and the Environment (Yale, 2007).

0