…and Its Internal Contradictions

Kevin Mattson’s impressively detailed account of United States punk in the first half of the 1980s persuasively demonstrates how a movement and subculture made up mostly of teenagers and young adults became one of the most important and radical challenges to the dominant politics and culture of the Reagan era. We learn how, after the initial wave of punk shocked and stirred American culture in the late 1970s, a new generation of punks took the reins, holding all-ages shows, making the music angrier (“hardcore”), and doing so in defiance of not just the mainstream music industry but also older punks and the hippie generation. On the latter, Mattson shows us how the abrasive energy of “teeny punks” punched a hole in the “mellow out” atmosphere of the late 1970s and contrasted sharply with the “yippie to yuppie” pipeline of the hippie generation.[1] Mattson illuminates how, as Reagan’s politics of unbridled consumerism, racism, and arrogant American international power set in, punk became a potent form of rebellion. Punks protested US intervention in Central America and the looming threat of nuclear annihilation, among other issues. The aptly titled We’re Not Here to Entertain also reveals how the entertainment industry, through its promotion of vapid consumerism, buttressed the politics and culture of Reagan America, and how punk, especially in its do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos, posed an alternative based on participatory creativity without the profit motive as its driving force.

The greatest strength of Mattson’s account of 1980s punk is its foregrounding of the agency of the people who made it happen. While bands are a central part of the narrative, we are also introduced to the wide variety of zine writers, artists, authors, filmmakers, activists, and other participants involved in punk. We learn that punk consisted of and inspired an impressive array of artistic expressions that have left a considerable impact on mainstream culture down to today. The structure of We’re Not Here to Entertain

highlights the agency of participants in punk by piecing together numerous vignettes which, combined, weave a larger narrative of creative expression and political resistance. Biographical details about punk participants highlight their individual decisions and actions while situating them in a larger historical context and in interaction within the punk scene, an entity full of debate and differences. We’re Not Here to Entertain never loses us in its sea of detail or plethora of punk participants by offering us recurring reference points—bands, individuals, and zine writers—who disproportionately shaped the direction of the punk scene. Mattson’s skill at storytelling—something many academics do not understand the importance of—makes for an exciting read in which larger conclusions and theorization come about through disparate threads coming together. As someone who ardently rejects the overuse of jargon and “theory” in scholarly writing, I find We’re Not Here to Entertain

to be a rare scholarly book that can resonate with a wide audience and give readers the feel of what it was like to be part of punk in the 1980s.

We also learn of the considerable impact of early 1980s punk on American culture. Mattson’s research draws on a wide variety of punk zines from all over the United States, all the way up to Anchorage, Alaska. This shows how the punk movement spread far beyond its early 1980s epicenters in Washington, DC, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Telling about punk’s impact is the backlash with which it was met. Mattson recounts the infamous episode of the Phil Donahue show warning parents against punk’s corrupting influence on their children. The book also analyzes how punxploitation films such as Class of 1984 and Suburbia painted a stereotype of punks as violent, drug addicts, and/or rapists (which, unfortunately, attracted some people to punk who wanted to live up to these stereotypes). Mattson is keen to demonstrate how the barter economy of the DIY punk scene and the network of underground shows, zines, and record labels posed a threat to the mainstream culture industry, though I think the suggestion that it was the underground economy that Reagan feared may overstate things. Reagan’s (rhetorical) fear of an underground economy was likely more rooted in racism than it was directed at the punk scene, and, as Barry Shank has pointed out, perhaps the punk DIY spirit had something in common with “the neoliberal belief in individualist freedom and entrepreneurial possibility”[2] that Reagan was championing at the time.

When reading We’re Not Here to Entertain, it is hard for me not to notice some striking parallels between the early 1980s and today. The deadly clouds looming over the heads of youth, then potentially nuclear, today climate-change driven, lead both to defiant resistance and to pessimism, despair, and nihilism. The “mellow out” Zen fascism that 1980s punk rebelled against sounds a bit like today’s trendy emphasis on self-care and meditation, and we are already seeing something analogous to the yippie to yuppie pipeline as many white middle-class Americans who proclaimed their solidarity with the slogan “Black Lives Matter” settle back into comfortable lives while (as I am writing this) thousands of Haitian migrants are being brutalized at the border and deported (so much for their self-care).

The hyper-reality Mattson describes bombarding youth in the 1980s—consisting of the new mediated stylings of arcade games, MTV, and blockbuster Hollywood films—has only become more pervasive with the new tools of addictive social media, constant attachment to cell phones, and ever more choices about what to use as distractions. Mattson’s mention of Reagan’s promotion, in early 1983, of arcade games as means to train kids to one day become fighter pilots is especially eerie considering how piloting the drones that the United States uses to murder people in Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, and elsewhere is all too much like playing violent video games on PlayStation, including through the detachment of the perpetrator from the atrocities they commit. These parallels between today and the 1980s are part of the reason that punk has remained a potent force for rebellion attracting new generations of youth—something Mattson downplays with his declension narrative of an early-80s punk glory days long since lost.

We’re Not Here to Entertain‘s embrace of early 1980s punk’s power as a force of protest and its creative capacity to carve out a culture of resistance is a welcome tribute to the agency of the those who made it. However, I see three weaknesses in Mattson’s narrative. First, there is a tendency to romanticize the punk scene and gloss over some of its internal problems. Second, Mattson’s eagerness to credit underground punk with being a force of resistance to Reagan’s America at times leads him to ignore or distort the role of other political, cultural, and social forces of opposition. Third, Mattson romanticizes DIY itself and presents it in opposition to a seemingly monolithic mainstream culture in which there is no room for dissent, and presents the decline of punk as being caused principally by its corruption by the mainstream music industry.

As for the first weakness, much as I think it important for any scholarship of punk to revel a bit in its liberatory energy, it is also incumbent on scholars of punk to dig into its internal problems. Mattson does acknowledge some of these internal problems and at times documents debates that took place within the punk scene, such as contention over whether it was appropriate for punk bands to propagandize their audiences with political messages or whether politics should be a personal choice (161–63). However, Mattson more often downplays some of punk’s more troubling tendencies in the early 1980s. For example, the turn from punk to hardcore in the early 1980s foregrounded a suburban white male subjectivity, which included misogyny, racism, and violence.[3] Mattson rightfully points out how punk voiced the anxiety of young males coming of age amid the newly established selective service registration, the growing potential of American involvement in war in Central America and global nuclear war, increasing divorce rates in the 1970s, and the growing prevalence of suicide especially by males aged 15–25 (17–18, 41–44, 64–65, 71–72). However, understanding these very real anxieties can let punk off the hook for its often misogynistic responses. Indeed, hardcore fashion and disdain for new wave artists such as Blondie was in part a way of excluding women. At its worst, misogyny in the early 1980s punk scene can start to sound like today’s so-called “incels.” It is possible to discuss this very real problem while keeping our sympathy for punk, and for the anxieties young men were confronting. Failing to do so leaves us less equipped to understand why tendencies towards macho violence, excluding women, and even glorifying rape became more full-blown in mid-1980s punk. My own research suggests that, owing to this state of affairs, it was not until the early 1990s that feminist strands of punk were able to gain traction—not necessarily because there were not any women asserting feminist critiques of punk in the mid-1980s, but because the (male-dominated) punk scene put up strong resistance to women playing prominent roles and asserting feminist politics.[4]

Likewise, early 1980s punk had a racism problem, expressed, for example, in Minor Threat’s anthemic racist backlash song “Guilty of Being White.” In the political struggles punk took up, the oppression of Black people appears to have been a lesser concern, even as the Reagan administration embarked on policies that were disastrous for Black people and appealed to voters using racist symbolism.[5] The punk scene itself was considerably white, and my own research into 1990s punk suggests that nonwhite identities were often ignored or suppressed in the 1980s punk scene.[6] Thus, when Mattson points out when punk bands did have Black or Asian members, it comes off a bit as a desperate attempt to show that punk was diverse rather than a discussion of what struggles went on within the punk scene over identity and racism within its ranks. Far from staining punk’s reputation, revealing shortcomings when it came to challenging racism or sexism is not just better history, it could also give us invaluable lessons for future cultures of rebellion. Considering that at the end of We’re Not Here to Entertain, we learn that skinheads became an increasing and violent presence in the punk scene in the mid-1980s, an examination of racism within punk may illuminate why racist skinheads had a relatively easy time encroaching on punk.

Mattson is entirely right to refute the mainstream media’s portrayal of punk as being misanthropically violent; however, it seems important to acknowledge that slam-dancing could be communal and liberatory or macho and violent (or even a mix of these different qualities). Furthermore, the Los Angeles punk scene of the early 1980s was plagued not only by police raids on concerts, but also by considerable violence perpetrated by a number of punk gangs. In their memoir, the band NOFX, who got their start in the early 1980s LA scene, criticizes the romanticization of that era and describes witnessing severe beatings, sometimes carried out for the sheer enjoyment of the attacker. They also note punk gang members who wound up dead, and they remember seeing a drunk girl being carried off to be gang raped by members of the punk gang “the Family.”[7]

This dark side of punk is not something historians should ignore, even if our focus must at times be on refuting media caricatures of punk.

I believe we can analyze misogyny, racism, violence, and other internal problems within the punk scene without joining the chorus of postmodernist academics eager to arrogantly point out the “problematic” aspects of this or that past culture or political movement from the perch of the ivory tower. Social movements are messy, and even the most liberatory are stamped by the oppressive societies they come out of. We need not condemn them for their shortcomings, but we can and should critically analyze them.

Another tension in We’re Not Here to Entertain emerges around Mattson’s rightful effort to prove the importance of punk as a challenge to Reagan-era politics, which risks presenting punk as the only radical game in town and the “conservative decade” of the 1980s as a straw man.[8]

Several times in the book, other forces of opposition to Reagan-era politics are written off or distorted. For example, Mattson’s characterization of the Nuclear Freeze protest in summer 1982 in NYC as merely a tame liberal show of moral opposition may be mostly accurate, but it reduces the large numbers of protesters down to a unitary position and fails to appreciate the importance of widespread sentiment against nuclear war (100–101). Mattson juxtaposes tame, ineffectual, routine protest with more militant, direct action protests by punks. I emphatically agree with Mattson about the need for protest to go beyond the bounds of “acceptable dissent” to be effective, but when Mattson writes off protests by the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES) for using protest monitors, he fails to consider that perhaps there were undocumented immigrants from Central America at CISPES protests, and the organization may have deliberately sought to avoid arrests for that reason (204).

Mounted police bludgeon El Salvador solidarity demonstrators outside of Henry Kissinger’s appearance at a Hilton Hotel, April 1984. Photo: It’s About Times.

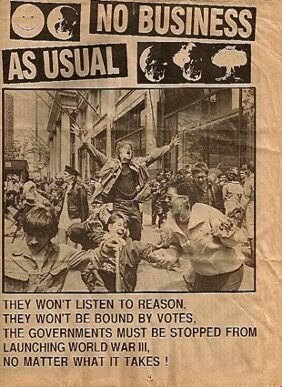

Furthermore, Mattson tends to credit punk as the only source of militant protest. For example, while writing off the Revolutionary Communist Youth Brigade (RCYB) as “wacky” (242), Mattson fails to mention its prominent role in the 1985 No Business As Usual protests against the threat of nuclear war (250–51). Mattson’s exciting description of the 1984 protests against the Republican National Convention credits punks with the militancy of the protest and mentions how Gary Johnson was arrested for burning an American flag, leading to a free speech case that would eventually go to the Supreme Court (206). Mattson leaves out the fact that Johnson was not a punk anarchist, but a member of the RCYB (something I learned from my high school civics class textbook). It appears that Mattson’s own ideological proclivities have led to some distortions of historical detail and a somewhat punk-or-nothing picture of militant, creative protests by punks and dogmatic or tame protests by everyone else.

No Business As Usual poster.

This tendency towards a punk-or-nothing narrative on the politics and history of protest in the early 1980s is likely related to the way Mattson at times poses the raw emotion of punk against intellectualism and dry theory, especially what he considers doctrinaire Marxism. This binary opposition is at odds with how We’re Not Here to Entertain reveals that many punks, especially those spearheading punk involvement in protest, were voracious readers and engaged thinkers. It leads to contradictory statements such as praising the Boston band the Proletariat’s song “Religion is the Opium of the Masses” for being driven by emotion, not theory, when it seems obvious from the song title that the Proletariat had read some Marx (163–64). Raw emotion, including as a means to express political viewpoints, is certainly one of the great strengths of early 1980s hardcore punk, which I cherish every time I listen to it, but we need not divorce this quality from the intellectualism of many of the very people who wrote punk lyrics and created the raw hardcore punk sound of the early 1980s. Emotions and thinking went together in punk culture; they were not necessarily opposites.

Finally, especially at the end of We’re Not Here to Entertain, Mattson poses the liberatory politics of punk against the hedonistic and materialistic politics of mainstream music. There is certainly a lot of truth to Mattson’s characterization, but he tends to presume a monolithic mainstream culture in which no dissenting viewpoints could break through to wider audiences. The interdisciplinary field of popular music studies has, for several decades now, demonstrated the ways in which popular culture is always a contested field, even if popular music scholars often go too far in asserting the potential for resistance within popular culture, failing to recognize the (greater) force of co-optation operating within the mainstream music industry. Perhaps more engagement by this intellectual historian with popular music studies might bring out a different framing of the relationship of early-80s punk oppositionality to mainstream corporate entertainment at the time.

Mattson’s narrative could do with a bit of nuance on this question rather than such a pronounced bifurcation. For example, Mattson’s only mention of the band The Clash comes as a passing reference within a discussion of the band Hüsker Dü signing to RCA records: “the Clash had sold out to CBS [Records] eight years earlier” (282). It is understandable why Mattson would not devote much attention to The Clash in a book focused on the American underground punk scene, yet given that The Clash had roots in the first wave of British punk, toured the United States in the early 1980s, played for sizeable audiences, and inspired many American youth during that time with the radical political critique in their lyrics (yes, disseminated through a major record label), they merit more than a passing negative comment. This shortcoming is particularly troubling given the importance Mattson places on punk opposition to US intervention in Central America. After all, The Clash titled their 1980 CBS-released triple album Sandinista! as a show of solidarity with the revolution in Nicaragua, and the album ultimately went gold. Is it really “selling out” if a band continues to espouse the same politics, but to a larger audience, after signing to a major record label? Does a historian have a responsibility to at least acknowledge the role of a mainstream punk band such as The Clash in inspiring audiences (including early-80s punks) with radical politics, even if said historian has an ideological disagreement with the very issue of signing to a major label? How do the actions of a band such as The Clash in the late 1970s and early 1980s in relation to politics and their involvement in the corporate music business relate to Hüsker Dü’s similar situation a few years later?

Mattson’s interpretation of the decline of punk in the mid-1980s is indeed that it was largely the fault of the mainstream music industry encroaching on punk. This may well have been a contributing factor, but what about the Nazi skinheads encroaching on the scene? As Mattson’s own research suggests, this was not the result of the mainstream music industry, but inspired by cassette tapes by the Nazi skinhead band Skrewdriver finding an audience in the US. Skrewdriver records were made and distributed the DIY way, via White Noise Records out of Los Angeles, were they not? Does this not suggest that DIY production and culture can also be used to organize people around reactionary politics? And what about the internal problems within the underground punk scene, such as its racism problem? What role did they play in its mid-1980s decline?

Mattson’s romanticization of DIY and antipathy towards any acknowledgment of contention within the mainstream music industry comes across most strongly in his summation of the rise to prominence of “alternative” music in the early 1990s:

Pondering his rock star success, Kurt Cobain, Nirvana’s lead singer, hoped new fans who were flocking the band’s way would be “exposed to the underground by reading interviews with us. Knowing that we do come from a punk rock world, maybe they’ll look into that and change their ways a bit.” Nice try. Why would anyone “look” or “expose” themselves to the “punk rock world”? It was being handed to them on a corporate platter, broadcast on MTV. And a platter that filled up fast, as major labels started signing other Seattle bands left and right. When Seattle had been sucked dry, it was onto California for the “‘East Bay’ pop punk” of Green Day and a whole host of other bands who had been connected, once, to a DIY experiment known as the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley, started in 1986 by none other than Tim Yo of MRR (286).

I might lose punk points for admitting this, but my own journey to underground punk came through the conduit of Nirvana, Green Day, and the Offspring (as was the case for many people, whether not they will admit it). I did exactly as Kurt Cobain hoped, making this initial exposure to mainstream alternative and punk bands the spark that led to me listening to Aus-Rotten, Los Crudos, and Detestation and joining in protests to free political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal. Perhaps it would be helpful if histories of punk moved away from DIY purity narratives and recognized the interaction, albeit uneasy and often antagonistic, between the underground punk scene and mainstream culture, as well as the internal contradictions and shortcomings of underground punk.

With all those criticisms of We’re Not Here to Entertain, I still cherish its embrace of the rebel spirit of early 1980s punk. If a history of punk is going to err on one side, I much prefer it to be that of romanticizing punk than criticizing it from the ivory tower. There is something truly romantic, in the best sense of the word, about punk as a potent force of rebellion against Reagan’s America. This is what Mattson’s book captures, not only in the details of each story it tells or its historical sweep, but also, most importantly, in giving readers a taste of what it felt like to be there.

Notes

[1] Of course, over the last couple decades there has been a punk to hipster pipeline that is the 2000s equivalent of the yippie to yuppie pipeline.

[2] Barry Shank, The Political Force of Musical Beauty (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 176.

[3] Probably the strongest scholarly documentation of this shift is in Dewar MacLeod’s Kids of the Black Hole: Punk Rock in Postsuburban California (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010).

[4] See chapter four of my book, Rebel Music in the Triumphant Empire: Punk Rock in the 1990s United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021).

[5] See, for example, Robert Dalleck, Ronald Reagan: The Politics of Symbolism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984).

[6] See chapter four of Rebel Music in the Triumphant Empire.

[7] NOFX with Jeff Alulis, The Hepatitis Bathtub and Other Stories (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2016), 21–24.

[8] One excellent account of punk’s role within the broader 1980s Cold War context is Raymond Patton’s Punk Crisis: The Global Punk Rock Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

David Pearson is a music historian, teacher, saxophonist, and composer. His book Rebel Music in the Triumphant Empire: Punk Rock in the 1990s United States was published by Oxford University Press in 2021. Recordings of his music can be found on Bandcamp. David received his PhD in musicology from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He currently teaches as an adjunct associate professor at Lehman College, where he has many frustrations with the ways in which students and adjunct faculty are treated by those in positions of power.

Author’s Note

Thanks to Trevor Lemke, SUNY Brockport student who was my student research assistant for this review and found the images and researched a number of important additional historical details.

0