The Book

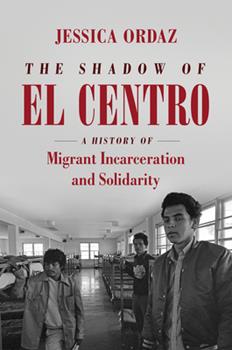

The Shadow of El Centro: A History of Migrant Incarceration and Solidarity

The Author(s)

Jessica Ordaz

Jessica Ordaz’s The Shadow of El Centro: A History of Migrant Incarceration and Solidarity uncovers the hidden histories and narratives of violence, dehumanization, and criminalization of migrant prisoners at California’s El Centro Immigration Detention Center. This work illustrates El Centro’s role not only in fueling the communities in Imperial Valley with antimigrant sentiment, but also its role as an institutional model for forced labor and criminal punishment upon migrant prisoners across the country. While Ordaz explores and analyzes these histories through interviews and images, she is also intentional in centering the stories of migrant prisoners in solidarity who were organizing against detention centers, in hopes of reclaiming their agency by resisting the oppressive powers of the state, in what she theorizes as “transnational migrants politics.”[1] The Shadow of El Centro takes a nuanced approach to current scholarship by analyzing the long and continuous histories of violence that have been prevalent in these detention centers from their inception, and not necessarily as a more recent product of neoliberal practices and policies.

Ordaz’s first part of the book, “Hauntings,” traces El Centro’s origins as a holding center that first opened in 1945 for Mexican immigrants, and its quick evolution into an institutional system of racialization, forced labor, and criminalization of migrant prisoners. Ordaz provides detailed accounts about the Mexican immigrants first held in El Centro and how they were used as a source of unpaid forced labor to directly contribute to the physical (and later ideological) expansion of this detention center and other labor intensive projects. Through various narratives, Ordaz explains how forced labor was a result of the power authorities exercised over migrant prisoners when it came to their survival (food/housing), and deportation decisions. From an ideological perspective, Ordaz grapples with shifting definitions of unauthorized migrants in a constant state of “illegality” and “legality.” She also refers to the implementation of the Bracero Program, which served as a way to move between legality and illegality based on whatever the needs of the labor market were. Ordaz also explores the impact beyond the need for migrant labor, such as the emergence of stereotypical and racist depictions of Mexican migrants. For example, Mexican migrants were being perceived as dirty or diseased, and the medical and scientific fields were also claiming migrants had certain biological traits that justified their ability to work in dangerous conditions, such as extreme and deadly heat. These historical accounts illuminate the intersections of politics, race, labor, and more that were at play, and the migrant prisoners who were dehumanized both physically and ideologically by being “racialized as nonhuman, criminal, and disposable laborers.”[2] On the other hand, Ordaz highlights the untold histories of migrant prisoners who were actively resisting these conditions by attempting to escape the detention center. In fact, she analyzes how migrant prisoners repurposed their illegal and legal statuses used to criminalize and dehumanize them, by voluntarily taking on the status of a fugitive to escape, therefore reclaiming agency, power, and freedom for themselves. Although escaping meant some restoration of power to these migrant prisoners, the more urgent message is that migrant prisoners were willing to risk punishment and even death, in order to escape the horrific conditions of the detention center.

In part two, titled “Ghosts,” Ordaz discusses the residual hauntings left by El Centro when it briefly closed in 1950, and how it served as a model for other detention centers; as well as its influence over U.S. citizens and government authorities to believe in the rhetoric that Mexican migrants were only valuable as cheap labor to harvest crops or were untrustworthy and dangerous criminals. Ordaz also provides further background on various legislation that effectively increased resources to enact more violence and power over migrants, such as the McCarran-Walter Act, Operation Wetback, and during the Regan era. She discusses this direct impact on migrants through personal stories about migrants being detained for long hours without food or access to a bathroom, and how even women and children suffered this same fate. Ordaz also considers the influx of Central Americans migrating to the U.S., often seeking asylum from war in their own country, which became further justification to provide even more power and resources to El Centro authorities that were already operating the detention center beyond capacity. But Ordaz makes an intervention here by discussing the new forms of resistance that emerged through transnational migrant politics. Since more Central Americans began occupying these detention centers, she argues that this afforded them “opportunities to foster solidarity.”[3] Moreover, detention center authorities exercised psychological and physical violence such as solitary confinement and beating migrant prisoners who sought information about receiving political asylum. This inhumane and unjust treatment spurred migrants to action to strike and organize alongside one another (some influenced by the activism they were part of in their home countries), to reclaim some of the power that authorities were trying to use against them. Ordaz illuminates the ways migrant prisoners resisted authorities in hopes of destabilizing their power over them through hunger strikes and refusal to work. Unfortunately, Border Patrol pacified the majority of protesters through violence, halting a lot of the momentum, and it was later justified that “the INS did not have responsibility to provide noncitizens with human conditions.”[4] Additionally, as a way to prevent hunger strikes from happening in the future, a Detention Officer Handbook was written with specific instructions on force feeding migrant prisoners. Nonetheless, Ordaz underscores the importance of these transnational migrant politics by reaffirming migrant prisoners’ reclamation of power and agency in using “…their bodies as tools to challenge a system that was never administrative but instead policed their physical movement and threatened their livelihood.”[5]

In the final part of her book, “Liminal Punishments,” Ordaz considers the gendered acts of punishment and surveillance that existed at the detention centers. She argues that these liminal spaces are examples of the “hidden history of abuse”[6]

where migrant prisoners were mistreated and physically abused (and it was not properly reported), which is why sharing these stories “historicizes their vulnerability and pain”[7] and makes them known and visible. During the 1980s and 1990s, there was increased policing against migrants and a racialized perception of migrants as criminals. Ordaz illustrates that with the implementation of ACAP and the IRP, the overarching message was that all migrants were perceived as dangerous or guilty of committing crimes. As a result, migrant prisoners held in the detention center were perceived as “criminals” deserving of any violent acts upon them, many times as a tactic for making them give up their asylum case so that they would agree to deportation. Unfortunately, even minors were treated just as violently as adults; in fact, Ordaz describes it as less about their age, and rather status. She argues that, “non-U.S. citizenship status meant that violence against their bodies occurred with impunity and that INS staff and guards did not see them as children or gendered as masculine”[8] and that young boys could be treated just as badly as an adult as a way to “prove they were real men.”[9] Ordaz also analyzes the bathrooms as a “liminal space for INS employees within the facility to enact violence on the bodies of the prisoners”, primarily because it is a hidden space. She explains that migrant prisoners were also expected to perform their masculinity, specifically by being able to endure the violence upon their bodies. Despite all of this, Ordaz argues that “migrants responded to this abuse by expressing alternative masculinities that included being vulnerable, showing solidarity toward fellow prisoners, and making claims on the state.”[10] Overall, Ordaz considers these hidden histories and recognizes those still not visible. Some of those stories are ones that were never reprorted, especially for migrants who died from medical conditions that went untreated or by suicide. Even further, the untold stories of all the unaccounted migrant lives lost while being held at the detention center, while crossing the border, or even on the journey back home after being deported.

In sum, Ordaz’s The Shadow of El Centro is a compelling work that exposes the hidden histories of El Centro and detention centers more generally, as institutions that were not simply a holding place for deportation, but rather a site of “exploitation, discipline, and abuse.”[11] Moreover, this work illustrates that these detention centers were developed to serve as a system of violence, abuse, and profitability based on forced and exploited labor. Even though El Centro has since shut down, the impact of the carceral state lives on in the Imperial Valley, as do the reverberations of mistreatment and violence toward migrants that still exist today. Ordaz’s work is a crucial contribution because it traces the long prehistories and histories of antimigrant violence and sentiment that continues to influence society today. More important, Ordaz’s work illuminates the hidden narratives of migrant prisoners, and elevates these stories of solidarity through transnational migrant politics, in order to emphasize that even in the bleakest conditions (and hauntings thereafter), migrants will continue to fight to be recognized for their humanity. Therefore, although some light has been shed on the shadows of El Centro, Ordaz’s work is a reminder to continue to interrogate these institutions, and uncover more hidden histories of violence and oppression on migrant lives, so that we may stop this cycle of suffering now and in the future.

[1] Jessica Ordaz, The Shadow of El Centro: A History of Migrant Incarceration and Solidarity (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 4.

[2] Ordaz, 30.

[3] Ordaz, 67.

[4] Ordaz, 88.

[5] Ordaz, 90.

[6] Ordaz, 94.

[7] Ordaz, 94.

[8] Ordaz, 100.

[9] Ordaz, 101.

[10] Ordaz, 108.

[11] Ordaz, 121.

About the Reviewer

Jeanelle Horcasitas received her Ph.D. in Literature/Cultural Studies from UC San Diego. She is a proud first-generation woman of color that comes from a working-class and immigrant family. Her dissertation “Reclaiming the Future: A Speculative Culture Study,” aims to amplify the voices and stories of Black and Latinx authors and filmmakers who use speculative fiction as a tool for social justice to reclaim and re-imagine more inclusive futures. She has held previous roles with Scripps Research, UC San Diego, and the San Diego Community College District. Jeanelle currently writes and researches educational content for developers as a Technical Writer at DigitalOcean.

0