The Book

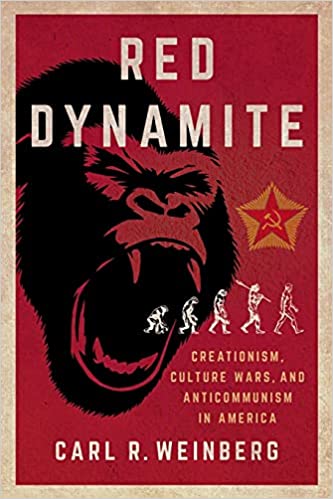

Red Dynamite: Creationism, Culture Wars, and Anticommunism in America

The Author(s)

Carl R. Weinberg

The word “and” does a lot of work in Carl Weinberg’s meticulous genealogy of American anti-Darwinist and anti-Marxist crusades. It’s there in the subtitle, linking three emphases that are commonly associated with evangelicalism/fundamentalism but not so commonly associated with each other. The word appears in almost every chapter title as well, in such evocative combinations as “Blood Relationship, Bolshevism, and Whoopie Parties” (chapter 3), “Flood, Fruit, and Satan” (chapter 6), and “The Nightcrawler, the Wedge, and the Bloodiest Religion” (chapter 8). An additive sensibility packs these chapters with people, publications, and institutions, all sharing ideas and often promoting each other’s work. Weinberg labels this sprawling family tree the “Red Dynamite tradition” (153), using a term coined by the Seventh-day Adventist and amateur geologist George McCready Price in 1925. The word “red” represented socialism, which Price saw (not inaccurately) as promoting evolutionary science against Christian dogma. Dynamite invoked both the frequent violence of the early twentieth century, such as the September 1920 bombing of Wall Street, and what Price viewed as the society-destroying power of Darwinist and Marxist thought. As Price described this incendiary mixture, “Marxian Socialism and the radical criticism of the Bible … are now proceeding hand in hand with the doctrine of organic evolution to break down all those ideas of morality, all those concepts of the sacredness of marriage and of private property, upon which Occidental civilization has been built during the past thousand years” (75).

You might be thinking, “Hold on there, George, you are cramming an awful lot of disparate concerns into that one sentence.” That happens a lot in this book. Revivalist preacher Mordecai Ham challenged jazz babies to cry out to their false gods: “Call upon your boxing matches, call upon your Venus, your Charlie Chaplin, call upon your evolution, call upon your modernist who makes my Christ the illegitimate son of an impure woman” (100). Henry Morris, author of The Genesis Flood (1961), decried, among other things, Hitler, Mussolini, racism, militarism, Freudianism, behaviorism, and Kinseyism, calling them all the progeny of Satan (178). Jerry Falwell lamented the baleful influence of “the abortionists, the homosexuals, the pornographers, the secular humanists, and Marxists” (233). These examples are chosen at random; you can find them every few pages.

The and-ness of Weinberg’s material can make reading the book feel a bit like handling a big ball of tar. Culture wars rhetoric is opaque and gluey, hard to analyze. Everything is stuck together, but it is unclear exactly why or how. It would be impossible to disentangle any discrete concepts, and anyway, the mass derived its cultural power from being a mass. To break it down into constituent parts would be ahistorical. The ball of tar accumulated adherents and smeared enemies quite successfully over the course of a century. It rolled from Price and William Jennings Bryan to James Dobson, Ken Ham, and the evangelical supporters of Donald Trump, picking up flotsam from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion

and the John Birch Society along the way. None of it made very much sense, but its conspiratorial illogic never impeded its work in the world.

As an explanation for phenomena like anti-CRT hysteria, the book succeeds, if anything, too well. (Other scholars have made similar connections, for example, Adam Laats writing for Nature in April 2022.) Conservative American Christians have, for at least the past 100 years, readily consumed scary propaganda that used faddish language to rile them up against their standard enemies: academics, uppity women, foreigners, people of color, Jews, anyone who dared to suggest that property should be shared more equitably. Although Weinberg doesn’t explore older antecedents, the propensity of American Christians to perceive themselves as locked in deadly battle with -isms could be traced all the way back to Puritan jeremiads. Samuel Danforth, in his 1670 “Brief Recognition of New-England’s Errand to the Wilderness,” asked, “How many Professors of Religion, are swallowed up alive by earthly affections? Such as escape the Lime-pit of Pharisaical Hypocrisie

, fall into the Coal-pit of Sadducean Atheism and Epicurism.” Danforth did not mean modernist professors of religion, but he set the pattern for amalgamated threats. The sum of the danger is somehow always greater than the menace of its parts.

Red Dynamite is less compelling as an explanation for evangelical Trump support, a topic addressed in the epilogue. To be sure, many of the ideas and figures from Weinberg’s latter chapters joined the Trump train; connections back to early twentieth-century populist anti-intellectuals are legible, and the paranoia about creeping socialism persists. Yet gender, the focus of books such as Kristin Kobes Du Mez’s Jesus and John Wayne, is not prominent in Weinberg’s book because almost all of the dozens of figures he introduces were men talking amongst themselves about subjects other than gender. Masculinity is assumed rather than analyzed. Anti-black racism also plays a fairly small role in Weinberg’s book, compared with the centrality of segregation in fundamentalist/evangelical identity and the patently racist anti-Obama backlash that propelled Trump to the White House. But this book is not really about Trumpism. It is about how anti-Darwinism and anti-Marxism, which might not seem to have much to do with each other, entwine throughout conservative Christian DNA. Weinberg has written the definitive account of that entanglement.

About the Reviewer

Elesha Coffman is associate professor of history at Baylor University. She is author of The Christian Century and the Rise of the Protestant Mainline (Oxford, 2013) and Margaret Mead: A Twentieth-Century Faith (Oxford, 2021).

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Love this review. The ball of tar analogy is effective—sticky, smearing, rolling, and accumulating detritus. And it’s flammable, perhaps perpetually on fire or at least smoldering. Thank you Elesha, and thanks to Carl Weinberg for writing the book! – TL