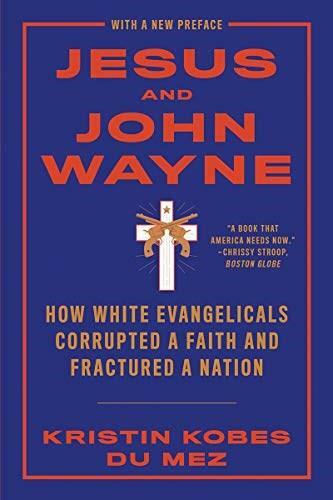

Kristin Du Mez’s bestselling Jesus and John Wayne (Liveright, 2020) upends conventional understanding about the white evangelical relationship with Donald Trump. When the 2016 election results revealed that 80% of white evangelicals voted for the irreverent adulterer, pundits scratched their heads before eventually assessing that support for the divorcee was strategic: evangelicals could count on the bankrupted billionaire to appoint conservative federal judges and Supreme Court justices to uphold and enforce their culture war goals in the legal system. For these prizes, evangelicals were willing to look past (and maybe even forgive?) his predilection for porn stars and profanity. Trump was tolerated as “someone who would break the rules for the right cause.” Du Mez argues that just the opposite is true. Trump was not the tactical “lesser of two evils” white evangelicals voted for while holding their noses. Instead, he embodied their understanding of Jesus, patriarchy, and militant masculinity as developed by Christian nationalists over the last century. This understanding has been literally sold, Du Metz argues, through a culture of religious consumerism. Decades of Christian books, magazines, television, music, family radio shows, children’s films, and other media and merchandise have created an omnipresent “evangelical pop culture” that continues to reflect and reinforce gender differences, patriarchy, nationalism, and white identity for the audiences that consume them. She demonstrates how political conservatives have harnessed the white evangelical vote by “offering certainty in times of social change, promising security in the face of global threats, and . . . affirming the righteousness of a white Christian America.” Evangelical community leaders and Christian consumerism reinforce the idea that political conservatives in the Republican Party offer similar benefits.

The strongest tie binding Christian evangelicals to Republican Party conservatives is a shared desire to see American masculinity become ruthlessly militant in the style of “cowboys, soldiers, and warriors” like Theodore Roosevelt, George Patton, and Oliver North. Faith leaders and cultural influencers have convinced the congregants who consume their messages and products that the Jesus of the Gospels was himself “a badass.” In promoting this characterization, political conservatives’ formula for winning the Christian vote means mobilizing them, in the warring spirit of the Good Shepherd, “to fight battles on which the fate of the nation, and their own families [seem] to hinge”—to convince them of their place in “a persecution narrative rooted in a sense of cultural decline” that can only be escaped through hard-fought cultural battles. Trump’s Make America Great Again approach promised to restore a mythological 1950s “John Wayne America” that white nationalist Christian warriors apparently longed to win back. The 2016 Republican presidential ticket featured Trump the strongman and Mike Pence the dyed-in-the-wool evangelical sidekick—a winning combination for white Christian nationalists.

Du Mez convincingly insists that the history of American Christianity is best understood as a “cultural and political movement” rather than a theology. It is one that does not begin or end with Trump. She presents this argument with a narrative history that begins at the turn of the twentieth century with Teddy Roosevelt and Billy Sunday. Guiding readers through the next hundred years, she explains how Christian nationalists have been shaped by church culture and conservative politics to think about “sex, guns, war, borders, Muslims, immigrants, the military, foreign policy, and the nation itself” for longer than a century. Given this emotional and political conditioning, it did not matter (and continues not to matter) that Trump embodied a poor example of a Christian because, as a Christian nationalist, “he could more than hold his own.”

Published a year before the January 6 insurrection, her analysis turned out to be frighteningly relevant, and it remains so even now that the twice-impeached former president is out of office. Her characterization of Trump as a leader who refused to let “the norms of democratic society keep him from doing what needed to be done” ends up serving more as foreshadowing than the author likely intended. Du Mez’s keen insight doesn’t just help us contextualize our modern political world; she also offers us a way to understand the international landscape of right-wing authoritarianism. Du Mez highlights how US evangelical groups have given more than fifty million dollars to right-wing European political organizations in recent years. She draws parallels between Trump’s election and how evangelicals in Brazil placed Jair Bolsonaro in office. Her observation about Billy Graham’s magazine Decision showcasing Vladimir Putin on its cover and heralding his homophobia shows a prescience about how interest in right-wing authoritarianism would develop. Now, right-wing American politicians and pundits express a fascination with Putin, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, and other corrupt autocrats.

Historiographical complements to Jesus and John Wayne include recent works in the history of twentieth-century Christianity and politics. Of particular interest to readers may be Anthea Butler’s White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America

(University of North Carolina Press, 2021) and Gene Zubovich’s Before the Religious Right: Liberal Protestants, Human Rights, and the Polarization of the United States

(University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022). Jesus and John Wayne is uniquely sourced materials from special collections at several Christian universities, including Calvin University, Pepperdine University, and Wheaton College’s Billy Graham Center. The author treats contemporary Christian literature and merchandise as primary source materials. The book is brilliantly crafted and argued, featuring cheeky chapter titles and a subtle narrative wit that readers will enjoy.

Du Mez is Professor of History and Gender Studies at Calvin University. She is also the author of A New Gospel for Women: Katharine Bushnell and the Challenge of Christian Feminism (Oxford University Press, 2015).

About the Reviewer

Lauren Lassabe is an Instructor of Higher Education at the University of New Orleans. Her book Resistance from the Right: Conservatives and the Campus Wars is forthcoming in 2023 from University of North Carolina Press. She can be reached at [email protected] and on Twitter at @llassabe.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thank you for this review, Lauren.

The more I meditate on this book, the more I want to hear Du Mez respond to political science research about voters who “hold their nose” and vote for the lesser of two evils. As a socialist, I do this constantly with Democrats. I find many liberal positions objectionable, yet I deal pragmatically with my ballots. I think I need to know what percentage of voters do that, or confess to doing it, before I can accept Du Mez’s argument about evangelicals. Note: I say this also as a former evangelical who voted for Republicans despite the inconsistencies I saw between their platforms and the gospels.

Otherwise I have little problem accepting the thesis of U.S. Christianity being a “cultural and political movement” as much as a religious one. I do think, temporally, that looking at Billy Sunday and TR as symbolic starting points for muscular Christianity serves as a fine anchor. But I think that certain twentieth-century decades introduce potential gender/masculine discontinuities—the 1920s and 30s, the 1960s and 1970s, and the late 1990s. These socio-cultural discontinuities surely affected masculine Christianity in the U.S. I say this, but perhaps Du Mez deals with these discontinuities successfully? I guess I need to get the book to work through her nuances. 🙂 – TL