Editor's Note

Today’s guest post is by Emily Hawk, a former S-USIH Henry F. May Fund Fellow and a Ph.D. candidate in United States History (ABD) at Columbia University. Her dissertation examines political commentary and community engagement in the work of postwar Black American modern dance choreographers.

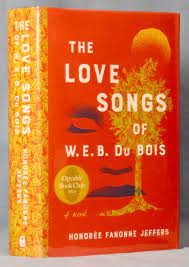

Two sisters read The Color Purple at bedtime. A family drives past a giant roadside peach. An historian carefully unwraps a photograph in an archive. These moments may not seem characteristic of an epic tale, but they belong to Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’s 2021 “kitchen table epic,” The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois.[1] The novel features a series of “songs” that recall the deep history of a Black-Indigenous family and intersect with the 21st-century historical inquiry of their descendent, Ailey Pearl Garfield. By braiding oral history with episodes of contemporary archival research, Jeffers’s narrative elevates the contributions of Black intellectuals and celebrates the historian’s craft. This stunning debut novel exemplifies how fiction writing can serve as a vehicle for intellectual history, suggesting that creative work can meaningfully convey ideas about the past and present.

Two sisters read The Color Purple at bedtime. A family drives past a giant roadside peach. An historian carefully unwraps a photograph in an archive. These moments may not seem characteristic of an epic tale, but they belong to Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’s 2021 “kitchen table epic,” The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois.[1] The novel features a series of “songs” that recall the deep history of a Black-Indigenous family and intersect with the 21st-century historical inquiry of their descendent, Ailey Pearl Garfield. By braiding oral history with episodes of contemporary archival research, Jeffers’s narrative elevates the contributions of Black intellectuals and celebrates the historian’s craft. This stunning debut novel exemplifies how fiction writing can serve as a vehicle for intellectual history, suggesting that creative work can meaningfully convey ideas about the past and present.

Enshrined in the novel’s title and embedded throughout its text are the intellectual contributions of “the Great Scholar,” W.E.B. Du Bois. Within the narrative, the reader encounters Du Bois through the character of Uncle Root, a history professor at a fictional HBCU and the protagonist’s great-uncle. Root met Du Bois in person as an undergraduate in the 1920s; he tells Ailey this anecdote several times throughout the novel, offering more details about Du Bois’s personality with each telling. He bestows Ailey with a first-edition copy of The Souls of Black Folk for her 16th birthday, introducing her to the concept of double-consciousness and Du Bois’s musings on the importance of Black women. As Root teaches Ailey about Du Bois’s ideas, he teaches the reader as well. In this way, Jeffers effectively uses characterization to share Du Bois’s real-world ideas with her readership.

Many of Jeffers’s characters are Black scholars and intellectuals in their own right. The career representation among Jeffers’s cast is striking, encompassing professors, medical doctors, principals, activists, lawyers, and pastors. These characters, particularly the four Black historians introduced across the novel’s 800 pages, advance Du Bois’s legacy by taking up scholarly work despite persistent racism in the academy. For instance, the protagonist Ailey – inspired by Du Bois’s teachings – enrolls as the first Black doctoral student at a predominantly white institution. Jeffers’s chapters on Ailey’s time in graduate school convey the emotional complexity of her experience: Ailey remains deeply fulfilled and inspired by her academic work despite facing colorism, racism, and sexism from her colleagues. Her research involves her own family history, and as she learns of her ancestors’ traumas, she is so overcome with grief that she must shower and pray after each day in the archive – a ritual she inherited from her undergraduate mentor. Jeffers describes these difficult moments without diminishing the exhilarating and empowering aspects of Ailey’s work. It remains clear that Ailey finds her scholarship exciting and fulfilling, even as it challenges her spiritually. In this section, Jeffers succeeds in capturing the humanity behind intellectual labor.

And finally, in her role as author, Jeffers herself takes up and extends one of W.E.B. Du Bois’s most important arguments: that Black artists, creators, and writers ought to be considered within the canon of intellectual history. In Souls of Black Folk,

Du Bois began each chapter with an epigraph combining lines of American and European poetry with bars of music from slave spirituals. In so doing, Du Bois placed the sorrow song on the same plane as the “high art” of poetry. He argued that slave music conveys something essential about Black American life, and therefore must be considered as a high art within the American cultural canon. As he wrote, “The Negro folk-song – the rhythmic cry of the slave – stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side of the seas.”[2]

Love Songs echoes this format with epigraphs drawn from the scholarship of Du Bois himself. But the book also references a number of Black creators and artists, including Donny Hathaway and Alice Walker, whose recurring presence in the narrative underscore their ability to interpret elements Black American life. Ailey herself is named for renowned choreographer Alvin Ailey, whose creative philosophy mirrors Du Bois’s argument about the place of Black art within the American canon. In his choreographic works like Revelations (1960), Ailey used Black American stories to share universal truths about humanity across lines of racial difference. It is fitting that Jeffers’s protagonist carries the name of such an important interpreter of Black American life. With this naming, Jeffers signals to the reader her conviction that culture and creative work can convey serious ideas.

Throughout The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers elevates the work of Black intellectuals while also contributing her own ideas about Black American life, work, and culture. Through her compelling characterization and sophisticated narrative-building, Jeffers uses both the form and content of her novel to argue for the intellectual significance of creative products. Intellectual historians are sure to find this epic novel thought-provoking beyond its sheer emotional resonance as a literary masterpiece.

[1] Jeffers describes her book as such in a December 2021 interview with Noel King of NPR [https://www.npr.org/2021/12/14/1064067022/reinventing-the-epic-with-the-love-songs-of-w-e-b-du-bois].

[2] W.E.B. Du Bois. “”The Sorrow Songs,” from The Souls of Black Folk”. Book excerpt, 1903. From Teaching American History. [https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-sorrow-songs/]

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

So beautifully measured and written. Thank you for this, Emily. I’m gonna read this novel now. It sounds like a profound expression of historical consciousness that in the same breath creatively does intellectual history. The ritual cleansing and prayer after the archives–just stunning.

Your essay made me think how, it seems to me one of the quandaries of what some people have called “the novel of ideas” happens in the expression of those ideas in the speech and dialogue among the characters, you know? (How the novelist sets that up.) There has to be some elegant vehicle for the thought of the thinkers considered (form) such that it makes sense within the world of the text (content). This can go really wrong in some hands. Judging from what you’ve written here–this attention to form and content–it sounds to me like this novel gets it right. Can’t wait to read it.

Thank you for taking the time to read and share your thoughts on the piece, Pete! I think the scale of this novel (800 pages, following the protagonist from childhood to adulthood) allows the author to infuse Du Bois’s real-world ideas without seeming too didactic, simplistic, or rushed. The reader learns about Du Bois alongside Ailey as she matures and ages, so the ideas seemed to evolve naturally along with the narrative. Of course, prior knowledge of Du Bois’s work certainly helped me notice when his ideas were at play. I wonder how such a balance could be achieved in a more concise format of fiction-writing!