I write today to mark the passing of Richard H King, who died this week. What follows isn’t a summation of his career. It’s more of a personal recollection of what he was like to know. I hope this gives some people solace. For those who didn’t know him,I wish you could have met him. Richard was beautiful. Now he’s gone, and I don’t know what to do.

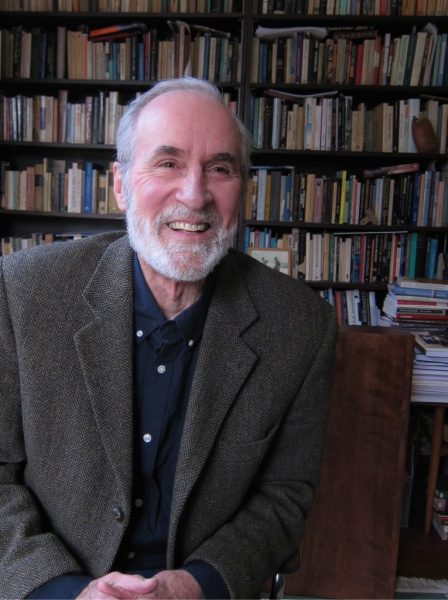

I suspect some of us in the Society got to know Richard over the years at least in some way. Maybe you all saw him at the odd USIH conference. He was that tall, thin, straight-backed, white-bearded Southern gentleman who loved to read books and talk about ideas. He read this blog regularly until he couldn’t nearer the end. I can hear that wonderful voice of his in my head as I write these lines. (“Any howlers in here?” Meaning: any purple turns of phrase or just plain contradictions in this one? Or “that dog won’t hunt.” Meaning: that argument doesn’t hold up, buddy.)

Richard was a mentor and friend to me, although I don’t know that he would have liked me calling him “mentor.” I knew him for around twenty years. It started when I was a graduate student at Vanderbilt in the early aughts, where he worked for a few-year stint between his many years at the University of Nottingham. He taught lots of students at Nottingham, and helped put together an unusually strong tradition of US intellectual history in the United Kingdom. I was introduced to the British Association for American Studies (BAAS) through Richard. I know that many people across the pond are mourning his loss. He opened me up to a world of cross-cultural comparisons and friendships.

For some years, we had a traveling conference show with a changing cast of characters. We were on lots of panels together. Those were always great. An image comes to mind of Richard at a table. He adjusts himself, clears his throat, lets out that characteristic light cough that lingered with him. He then launches into an impossibly erudite, at turns serious and wry, witty discussion of this or that topic, categorized usually according to three or four big concepts or themes. He finishes, nods his head at me, maybe sticks his tongue out to see if I liked the jokes. Not too bad, Richard. He plied that bit of understatement if something he read struck him as really good stuff: “That’s not too bad!”

Richard genuinely loved ideas. That sounds precious, but it’s not. The big ones, the persistent ones. He loved to explore them, grapple with them, experiment with them, tell jokes about them, ponder their implications. He introduced me to just about everything worth knowing. He wouldn’t have liked me using the word “mentor,” because he never liked the power dynamics in words like that. He never wanted a school of thought around him, and he was wary about the careerist side of the academy. Yet, he helped any number of people on their career paths. After his last book on Hannah Arendt, he spent some time on the concept of goodness. Just what did it mean to be good?

Richard read more widely than anyone I knew. If you said you were interested in some question he would just say something like, “you could maybe do worse than read x, y, or z for more of those ideas.” Or if you told him you were reading this or that book, he would say, “if you’re into that, you might could check this one out. It’s good.” He was always reading something interesting or going back over books in philosophy or literature. We read books together and talked or emailed about them, or we shared ideas we found in things we read independently. He had much longer term friendships like this with others, especially Steve Whitfield and Larry Friedman. I heard about those conversations mostly second-hand. I would love to read just some of those someday. He said he never felt right if he didn’t read for a few hours a day. Toward the end, he could no longer read, and I shudder to imagine how that felt to him. At turns he could be hard on himself.

He never saw the allure of, say, Jamesean pragmatism. I don’t think he ever quite appreciated why I kept going back to William James. Why read Bill James when there were so many ideas written by German thinkers to figure out? Why not Arendt or Freud, the Frankfurt School, or Faulkner, or CLR James? He was always game to read things together, though. I recall once we had the idea to read Heidegger’s Being and Time with a group of grad students I put together back in the Vanderbilt days. (For those in the know, Heidegger is properly pronounced “Haah-degur.”)

The thing is, we read that just to read it. The first meeting we had around ten people. The next, maybe eight. Eventually, one morning it was just me and Richard. He said something like “well, I suppose we keep on?” Maybe some of us were fortunate enough to be in one of his reading groups. A longstanding one he began with Michael O’Brien in the UK still goes on today. The pre-conference reading group we sometimes have at USIH conferences originated from that group.

Richard thought with rigor, and he judged others’ work with rigor. He was honest. He didn’t suffer bullshit or false praise. He was encouraging when it mattered. I came to think Richard thought it a moral obligation to give people genuine feedback. It would be condescending not to do that. That was love in the fullest Aristotelian sense of friendship.

I thought he hung the moon, but I never let on too much, because it would have been weird for me to say that. (I think he figured it out. I suspect there were rumors.) Richard had exquisite manners, but he wasn’t a stick in the mud either. He didn’t take himself too seriously. His sense of humor was warm and self-deprecating. He enjoyed a good turn of phrase—especially Southernisms—and a good joke. He liked to kid around. His musical inclinations tended to country, bluegrass and jazz music among other things. We had a long stretch of conversation about Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray’s letters to one another about music, Trading Twelves. He met in a regular group over in Nottingham where they listened to music and talked about it.

Richard never could get along with some of the “alt-country” or punk rock-inspired stuff I was into when I met him, but he listened to it anyway when I forced it on him. Why listen to that stuff when the “possum” George Jones still trod the earth? He loved George Jones like some kind of Nietzschean monumentalist. There was something inimitable about George’s pain in that voice, why he drank, was so self-destructive, and so on. No one could hit you in the gut like George Jones.

To haze him a little, one time I sent him the metal band Mastodon’s song “Blood and Thunder” owing to it being about Melville’s Ahab. His response was classic: “I listened to it three times, Peter, and I couldn’t make out the half of it.” He listened to it three times. We agreed on most jazz and minimalist music. I tended to get more out there, but he always listened to things I turned him on to, and I listened whenever he sent me things.

Most every time he came to Nashville, we ate barbecue. I customarily came with a Memphis rib rub for him and his partner Charlotte when I came to visit. I don’t think he could get a great barbecue rub over there. He made Southern style ribs in the oven and shared it with people. He and Charlotte’s hospitality was always so gracious in that beautiful old house crammed with books and art. A great part of the fun visiting over in Nottingham was talking to Charlotte over breakfast or lunch. She is an endlessly brilliant, curious person, which was something they shared.

There is so much more to say, but I don’t know how to say it. He changed my life and many others besides. His passing feels like the end of something irreplaceable in the world. I don’t know what to do.

I suppose we keep on.

9 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Pete: Thanks for this wonderful reflection. My longest sustained, in-person interactions with Richard came in 2018 at the Dallas conference. In the pre-conference book club we discussed Arendt’s *The Human Condition*. In listening and observing Richard with the group, over several hours, I obtained a small but delectable taste of what you have described above. We can’t have too many congenial, welcoming, and generally friendly historians in S-USIH. It’s a trait that’s become unfashionable over the past few years, due to a variety of circumstances. I think all of could use a strong dose of Richard’s personality and presence these days. – TL

Thank you, Peter, for this vivid, charming, accurate and apt profile of Richard. You capture his special and especially his generous qualities. We knew one another since the early fall of 1964, in graduate school at Yale; and a few years later, I remember telling a mutual friend, who asked me about Richard, that “he has no faults.” I still think, after nearly six decades of close friendship, that that offhand remark was right. Your reminiscence also gets right how much Richard was at ease in both western European thought and in American Studies. My only quibble with your piece is that the breadth of Richard’s musical tastes were remarkable. He loved chamber music too. Your capacity to capture his mind and spirit and legacy is cherished. As ever, Steve

Thank you Steve. That’s right. He did love chamber music. We talked about Alex Ross’s book on twentieth century music more than a few times. (He liked it quite a lot.) Richard also had astute opinions about visual art. His curiosity and breadth of observation was pretty much boundless.

I grew up with Richard in Chattanooga back in the 50s. In the memorable summer of 62, he and I drove to Washington state and worked in the Ora fields for a time. In our off times we read a lot. He has been my best friend for these many years and his passing leaves me in tears. Words fail me. Jim Hilton

My condolences, Jim. I would love to hear more of that story and many others besides some time, when you can.

I made a typo in my submission. It was pea fields not Ora.

Richard is a great loss. In 1994, I organised a conference at The University of Warwick, ‘Contemporary Perspectives on US Southern Culture’. Richard spoke at it and afterwards I asked tentatively if he’d be prepared to co-edit a volume of the talks. The book, Dixie Debates: Perspectives on Southern Culture, was published by Pluto Press in 1996, and received considerable acclaim. Richard was a wonderful co-editor. We wrote a joint introduction and he wrote a splendid Afterword; his editing was masterful and his collaborative spirit and work remarkable. I didn’t know him well before, but I grew very quickly to admire and like him. He was courteous and thoughtful, and a fountain of knowledge and references. We lost touch but I recall him with great fondness.

Thank you for this wonderful eulogy, Peter. You made me cry, honestly. You’ve summed up my own thoughts and feelings about Richard and you have captured his kind and generous essence as a man and a scholar. I didn’t know him as well as you did – we met in person only a handful of times – but we had lengthy email conversations that ranged across history, politics, philosophy and other more personal subjects. We talked for a long time about Winthrop Jordan, who had been my teacher at Ole Miss, for a retrospective Richard wrote for the USIH blog. I first met him, as you did, at Vanderbilt but have seen him more often here in the UK (I am in Liverpool) and last saw him in 2018 in Nottingham. Anyway, Richard wrote a letter of reference for me so I owe him my job, and so much more beside. We will all miss him and the values he carried with him so much. Thanks again,

Richard was a wonderful human being. I was married to him for 12 years and will always treasure those memories. We lived in Charlottesville, VA where he completed his PhD, then Washington DC and then Nottingham, England. We continued to keep in touch over the years. Nancy