If you are not Extremely Online, 1) congratulations, but 2) you probably missed the conversations prompted by this remark from Kieran Healy, a sociology professor at Duke:

A somewhat odd trend in Academic Twitter discourse is TT faculty who say they won’t consider giving an ordinary departmental talk in their own discipline unless there’s an honorarium involved, and who insist that being invited to dinner by your hosts is a really a sort of insult.

— Kieran Healy (@kjhealy) November 3, 2021

Lots of people weighed in, and lots of comments addressed important issues. Is the implicit expectation that scholars will speak at one another’s institutions without remuneration a relic of a vanished political economy of higher education? A sign of immense privilege and security? As more and more scholars find themselves precariously employed or tenuously connected to institutional stability, shouldn’t they be paid for their labor? What might seem a fairly low-stakes use of time and talents for some can actually be very costly and draining for those upon whom the burdens of academic labor already fall more heavily. Is “doing it for exposure” just another name for exploitation?

There’s validity in all of these observations and objections.

I would say that it’s not helpful to assume that a scholar of any status should be willing to give a talk without remuneration, but it’s also okay as a scholar of any status to choose to give a talk without remuneration if they are able to do so and wish to do so. But I hope they will be explicit with their hosts about that choice, encouraging them to try to pay the next guy.

Now I’m gonna lay my cards just right down on the table…

I am currently positioned entirely outside the economy of academe because I lost my job. (Google it.) However, I still want to take part in the scholarly community, and that depends entirely on a few things, including these: being invited or included, and being able to afford it.

I’ve been blogging here since January of 2012. Blogging is a way of participating in the scholarly community, though it’s not scholarship—and it’s not paid. Everyone who has written for this blog or edited this blog or made a guest contribution has done so as a volunteer. For some, it is “service to the profession” that may count for promotion and tenure. For most, though, it has been unpaid labor.

That’s not to say that writing for a thoughtful audience of general educated readers and fellow specialists isn’t rewarding. Every writer appreciates a readership—or they should! And of course the gig pays in that volatile currency we academics use for scrip or for scandal in equal measure: “exposure.”

And “exposure”—or, more politely, reputation—is absolutely essential for participation in the scholarly community. We must know one another, we must learn what others are working on, others must know what we are working on, and writing for a public audience is one way to get the word out and to help create and sustain a community of people who share a mutual interest in each other’s research. Conferences are another way to do that—putting together a proposal, attending a session and asking questions, saving up all our extrovert minutes so that we can handle walking up to strangers and introducing ourselves and making acquaintances and friends. Building connections is important, professionally, and the less prestigious your position the more important those connections are.

But, looking back, I’m actually glad that I didn’t really understand this about academe when I started commenting here pseudonymously and even when I started writing here. I was just very happy to find people who were interested in stuff I was interested in, and who would put up with my thinking-things-out-through-writing, and who were fun to be around in person. Had I started out with the idea of “developing contacts” or “building an audience for my scholarship” I don’t think I would have built the lovely relationships that I have with so many people in academe. When you set out to instrumentalize others, you may get use out of people, but you won’t make friends of them.

I would rather have friends.

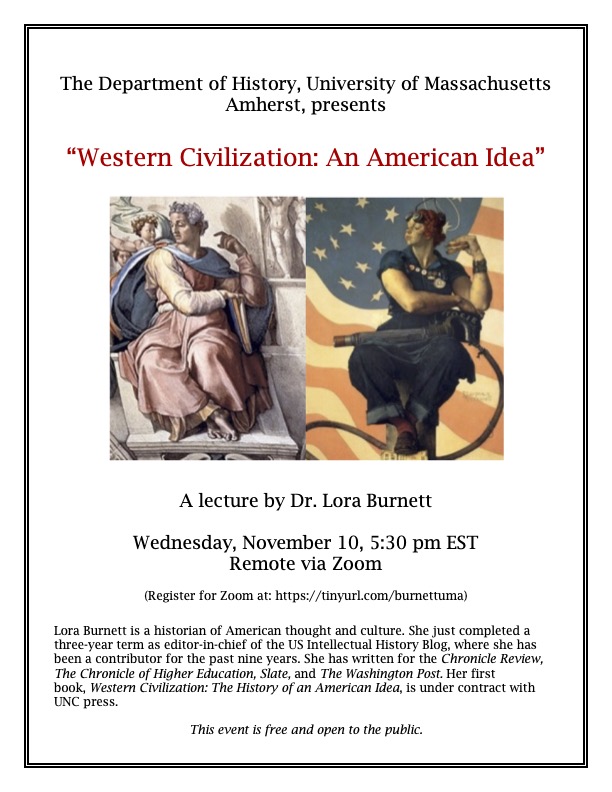

I am giving a talk via Zoom on Nov. 10.

Now, that’s a sincere sentiment. But that’s also my privilege talking: I could afford to be in academe with the aim of making friends because I was not the sole wage-earner in my family. I could participate in the scholarly community without having to make it also pay the bills. That said, losing my academic job means that I no longer have the resources to participate at the level I would like to. Accepting an invitation to participate in an academic conference or be part of a panel or give a talk means finding the money somewhere, and it’s a lot harder to find in a one-income household.

But back to my cards…

When it comes to giving a talk, or presenting my research, or attending a brownbag, or even participating in an invited panel, I will accept an honorarium when one is available, but I will do my best to show up anyhow when an honorarium isn’t offered. Not because I need any more “exposure”—I’m good; thanks!—but because I enjoy taking part in this scholarly community and I want to pay it forward as I can.

And I think this gets back to Kieran Healy’s bemusement. Academics who are in a position to reciprocate professional courtesies—they have institutional financial support, job security, the freedom of a flexible schedule, the freedom to cancel a class or be out of town for a day—might normally choose to give a talk without an honorarium and then extend an invite to another similarly secure scholar for a similar event at their own institution. I mean, I don’t know for sure that this is how it works—never been in those positions. But I can see that kind of ethos operating in a certain segment of the academic economy.

Unfortunately, I’m not in a position where I can reciprocate any professional courtesies. I have no institutional affiliation I can use to help someone else find an interested audience for their work. I have literally nothing of professional worth to offer anybody now. I can’t invite you to speak to my department. I have no department.

I’m busted.

But I’m not broken. I still work as a scholar, and I still want to share my work. So even though I’m in a more precarious situation financially than I was at this time last year, I will still accept invitations to speak whenever I can even when there’s no honorarium.

Please invite me to share my work with your class, your department, your college, your conference. Yes, I value my time and my intellectual labor, and I also value every opportunity to participate in the scholarly community. Whenever I can afford it, I will choose to participate. When an honorarium is offered, I’ll gladly accept it. But when remuneration isn’t available, I will still show up as I can.

But that’s my calculus, and it’s not broadly applicable. “Middle-aged upper-middle-class white woman scholar with no teaching load because she got canned” is a really unique position to be in. One should not draw general conclusions or rules of thumb from my situation…I hope!

What I draw from the recent discussion about honoraria is this: offer one whenever you can, whenever your institution or your department or your program has the resources to do so, however small the amount may be. The political economy of academe is collapsing, so it’s always good to pay folks in real dollars in addition to exposure. If you can’t afford to offer money, maybe there’s something else you could offer: visiting scholar status, access to research resources, review and critique of a work in progress. But it’s not gauche or somehow insulting to the Spirit of Academe to offer somebody money in return for even a casual speaking appearance. And it’s absolutely okay if, when you offer money, your invitee actually accepts it.

So yeah: I will give a talk for free, whenever I can, wherever I can. My access to and participation in the scholarly community now depends entirely upon the willingness of others to invite and include me. And honestly? Sometimes just being invited feels like winning the lottery.

Yes, it’s true: I still want to sit with you nerds. Please save me a place at the table.

0