The rules of Password are pretty simple. You divide up into teams with one two or more players on each team. One member of the team draws a card with a secret word or phrase, and they must describe the word—which could be noun, verb, or adjective—without using any part of the word or phrase being described. If your team guesses the word while the egg-timer runs, you get a point. If after the end of your team’s turn the other team guesses the word, they get a point.

So, for example, if you drew the phrase “happy days,” you could say something like “they’re here again, and the skies are looking clear again.” Or you could say, “A 1970s TV show with Fonzie and Richie.” But you couldn’t say “jubilant days” and you couldn’t say “happy 24-hour-periods,” because both of those descriptions borrow a term from the term you’re definining. That’s the big no-no, the key restriction of the game.

When I was learning Spanish, my third year teacher played a version of this game in class. He called it “definiciones,” definitions. The rules were pretty simple. He would call on you, give you a vocabulary term, and ask you to define it in Spanish. So, for example, if he gave you the term “anteojos,” meaning “glasses” (literally “before the eyes”), you couldn’t say “los lentes que se ponen ante los ojos para ver” (the lenses you put in front of the eyes to see). You had to use completely different terms than the ones given to you. So you might have to say something like, “los lentes de vidrio que se ponen en frente de los organos de ver para mejorar la vista” (the glass lenses that you put in front of your organs of sight to improve your view).

Your definition might be super clumsy. It might be inaccurate. It would definitely be periphrastic. And that was precisely the point. The crucial idiomatic skill this drill fostered was the abilty to describe something for which you did not know the word. That’s a path to and a marker of real fluency in another language.

There’s another name for using part of the term you’re defining to define the term you’re defining: begging the question. It is so hard to avoid.

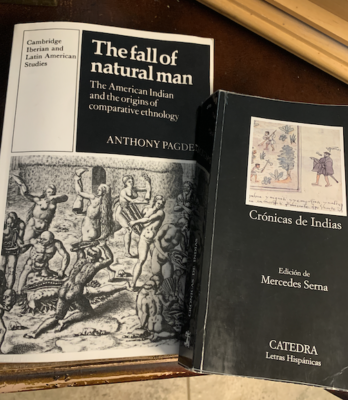

I am currently reading Anthony Pagden’s monograph, The Fall of natural man: The American Indian and the origins of comparative ethnology (Cambridge, 1982). This is a work of intellectual history very much of the Cambridge school, paying close attention to the meaning of words within the context of their larger discursive milieu. This kind of history focuses almost exclusively on formal propositional thought—theology, philosophy, law, and so forth.

I am currently reading Anthony Pagden’s monograph, The Fall of natural man: The American Indian and the origins of comparative ethnology (Cambridge, 1982). This is a work of intellectual history very much of the Cambridge school, paying close attention to the meaning of words within the context of their larger discursive milieu. This kind of history focuses almost exclusively on formal propositional thought—theology, philosophy, law, and so forth.

Pagden’s work explores how sixteenth-century Spanish arguments over the nature of Indigenous people, drawing from and modifying the anthropological theories of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, ended up situating Indigenous Americans squarely among the larger family of mankind, but situating them as people whose potential for fully actualized life had not yet been realized and could only be developed as they adopted Christian ways of thought and living. Crucially, though they may have been “men of nature,” they were not “natural slaves”—and drawing the difference between these two concepts, in order to reject the latter as it purportedly applied to Indigenous Americans, was a key contribution of the Salamanca school of Spanish thinkers.

The scalpel-like precision with which a figure like Francisco de Vitoria handled the terms of Aristotelian political and anthropological theory pointed the way for a much less subtle, much more polemical argument from the same terms by the self-appointed defender of “los Indios,” Bartolomé de las Casas.

One of the issues tackled by the scholastics and the polemicist alike was the prejudicial meaning of the term “barbarian” as applied to Indigenous Americans.

Pagden writes,

The trouble with a term like ‘barbarian’ is, of course, that it is both a classification and an evaluation. It does not derive from the need to categorise something ‘out there,’ as botanical and zoological terms do, but, as we have seen, merely serves to express a sense of the difference felt by one cultural group when confronted with another of which it has had no prior experience. (124)

Though Pagden here discusses what the trouble is, as if “barbarian” is a historic constant in terms of its meaning, I think this particular “is” operates within the context of 16th century European thought. In other words, I think Pagden’s present-tense here is not our own day with our own senses of the meaning of “barbarian.” Rather, Pagden’s statement describes the problem as it appears in its 16th century milieu.

Indeed, Pagden returns us to that milieu just a few sentences further down the page.

When with the discovery of America this ill-controlled tem was put to use as a precise social category, some confusion and a great deal of concern over definitions were bound to result.

For although barbarism was evidently a cultural condition, the term was, as we have seen, frequently used simply to describe non-Christians. Unless, therefore, he was of the opinion that all non-Christians were culturally deficient, a position which in view of the Christian debt to the ancient world it was hard to maintain, the user of such a word was faced with the necessity of saying more, sometimes much more, than he intended.

So far so good for Pagden, who takes us back to what barbarism “was.”

But then, with just two more sentences, Pagden slips, and he pulls the 20th century world of thought into the sixteenth century, anachronistically naturalizing an antonym for “barbarian” that rolled easily enough off his own pen but not so easily off the quill of the source he quoted.

Here’s where he slips:

This [uselessness of the term ‘barbarian’] was apparent to contemporaries. Cortés, for instance, wondered how it was that a people such as the Mexica could create a sophisticated material culture, ‘considering that they are barbarians and so far from the knowledge of God and cut off from all civilised nations.’ (124-125)

If you read that sentence, you would be excused for thinking that I have been misleading you here, in my long-running argument that the concept of “civilizations” or even “civilized nations” was not available to the European mind in the sixteenth century, particularly when invoked as the opposite of “barbarians” or “barbarism.”

But you would be mistaken.

Pagden is quoting here from a translation of Cortés. In fact, in one of those droll little exercises of self-citation, Pagden is quoting here from his own translation of Cortés.

And Pagden’s translation of Cortés, at least here, renders the conquistador comprehensible to a contemporary audience at the expense of fidelity to Cortés’s thought in its own time.

Here’s what Cortés actually wrote: “considerando esta gente ser bárbara y tan apartada del conocimiento de Dios y de la comunicación de otras naciones de razón…” (from Crónics de Indias, ed. Mercedes Serna, pg. 271).

You can see the Spanish cognate of “barbarous” there, but you will look all day and never find the cognate of “civilized.” It wasn’t around for Cortés. He couldn’t have used it. Instead, he described “other nations of reason,” or, “other rational nations.”

I am not taking issue with Pagden’s scholarship on the 16th-century battle over appropriately labeling Indigenous Americans. Indeed, I am leaning heavily on it. But even a historian as brilliant and incisive and attentive as he is to the nuances and complexities of a discursive context can occasionally fall into anachronism. Pagden’s translation of Cortés was an unfortunate anachronism because it naturalized the barbarism/civilization dichotomy of the 18th century and later and plunked it into a 16th century context.

This is perhaps a small issue for Pagden’s argument, but it’s a big issue for mine. When I said earlier that I was rowing against the current of our entire discipline, this is the kind of thing I meant. Every time a scholar describes someone from the 16th century as discussing or mentioning “civilization,” I have to go back and check the language of the original source. And there’s more source than I’ve got language, I’m afraid.

Sure, to us today Cortés’s language reads like a rather awkward paraphrasis for “civilization,” and it would be easy enough to drop in that word so familiar to us to make the text flow smoothly. But this translation, which is Pagden’s choice, elides exactly what was so unsatisfactory about the term “barbarism,” never mind that it completely obscures the crucial knowledge that “civilization” is a concept that comes out of these sixteenth-century European debates. It’s not there for them at the start.

Urbanity, civil society, politeness, decorum, ceremony—all those concepts were ready to hand for Columbus, for Cortés, for Vitoria, for Las Casas. Out of the clash of those concepts with other terms, including “barbarity” and “barbarian,” a more modern conception of “civilization” emerges. But that takes time, and the passage of time in which this occurs makes for a very particular historical contexst.

So, getting back to Password, you can’t use the word you’re historicizing to describe the context in which that word developed. I can’t historicize “civilization” by drawing from sources that describe people invoking the term before it existed for them. Maybe Pagden can beg my question, but I cannot.

This brings me to my problem:

Do you have any idea how many works of history written since the 18th century use the word “civilization” as if it were a natural category of thought not only for us but also for all who came before us?

Almost all of them. Honestly. Almost all of them.

And I’m here to tell you that they’re. all. wrong.

To use another phrase Cortés could not have thought, I am tilting at one hell of a windmill.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Having been confused by your previous post on this subject, let me thank you for this essay. Now that you have made some of the translational issues apparent, I think that I get it. I just read a section of Mary Beard’s SPQR where she uses the word “civilization” in a way that reminded me of your writing and puzzled me. I don’t think she was quoting an ancient author at the time but I am pretty sure that she could be read as saying that the Romans thought of themselves as the “civilization.” It is a convenient shorthand for a modern reader and I’m sure Prof. Beard has to take many shortcuts to tell the history of Rome in a few hundred pages. “Civilization” becomes something new for me to keep my eye open towards and to think carefully about.

Thanks for your thoughtful essays on work in progress.

This is the most encouraging comment I have ever received on anything I’ve written. Not kidding. You give me hope that my argument will make sense to someone.

And of course anyone who is NOT focused on historicizing the idea of “civilization” can use the word in their writing as a shorthand term familiar to us all. If I were teaching a course in world history, I would have units on “Mesopotamian Civilization” and “Egyptian Civilization” and “Greek Civilization” and “Roman Civilization” and “Songhai civilization.” I might mention that “civilization” is a new-ish term and not what these peoples called themselves, but I would resort to the word as an anthropological term that implies a set of characteristics: cities, highly hierarchical society, system of writing or recordkeeping, division of labor, metropole with client/satellite polities, a systemic approach to justice (legal code or auditors/courts of some kind), etc, etc.

It’s a useful term for all kinds of historical writing…except for the kind of historical writing whose purpose is to historicize the shifting valence of the term “civilization”!

But thank you, so much, for letting me know that you see what I’m doing here. I am now writing this book for you.

Thanks for this interesting insight. Does Pagden discuss the linguistic argument centered around the original employment of the term “barbarian” by the Greeks (and their need to classify foreign-speaking peoples)? At least, that’s my understanding of the Greek/barbarian dichotomy. It seems like the American Indians’ physical differences (including their material lifestyle) were more noticeable than their language (although noticed). Are you arguing that the new idea of civilization is “new” in this different focus (by the Spaniards, etc.)?

Speaking of David’s comment on “shortcuts,”I do think there should be study of how evolution/Darwin created a Whig version of history (that is apparent in 19th-century anthropology paradigms for how the past was “organized” [to use Butterfield’s exact term]). Maybe there is one already; most works on historiography tend to treat this evolutionary framework in short bits and pieces, but never amounting to totalizing methodology.

Per Pagden: In his Apologia from the Valladolid debate, Bartolomé de Las Casas maintained four distinct meanings for the term “barbarian.” The first definition is a little different because it applies not to groups of humans but to individual people.

Barbarian, definition 1: an individual who has temporarily lost his reason, lost control of his passions, etc. Think of a soldier overcome by the rage of battle who begins to commit atrocities that fall beyond what is considered just or acceptable in warfare. A violently irrational man.

Barbarian, definition 2: a society characterized by a failure of men to understand one another, by a failure of language to bring about comity, and, more specifically, by the lack of written language to record or preserve laws. without a written lanugage, custom and tradition take the place of codified law, and the polity is governed through the charisma of its leaders

Barbarian, definition 3 (the rarest kind): those men who have no capacity for cultured or ethical life; the “natural slaves” of Aristotle’s conception. this was a category that Ginés de Sepulveda wanted to apply to most Indigenous people in the Americas, hence Las Casas’s argument for its rarity.

Barbarian, definition 4: all those who are not Christians

As you can see with definition 2, Las Casas refined the meaning of “barbarian” in re: language, so that it was not simply “those who don’t speak Greek” (or, for Las Casas’s time, Latin), but “those who don’t have a way of recording their speech, in whatever language it is.”

Later — and by later I mean during the 18th century — the presence of a written language becomes one of the criteria for identifying a “civilization.”

There’s still no conception of “civilization” in Las Casas’s time, though he himself kind of paves the way for it. Per Pagden, Las Casas’s key contribution to anthropological theory is the argument that the newer the polity, the more likely it was to be barbarian. He argued that the Indigenous Americans had come to their land later than all the other known peoples of the world, had had less time to develop customs, traditions, language, etc. Thus he argued that there was no essential distinction between Indigenous Americans and any other group of people–they simply needed time to develop.

This is the revolutionary contribution of Las Casas, per Pagden, to social thought. Two centuries later, we get Pufendorf and Adam Smith and their theories of stages of human development. But that situation of human cultures in historical time, and the explanation of cultural differences as being related to how long a society has existed (rather than to some essential difference between men of different cultures) is new, Pagden says, with Las Casas.

So if you want to find the origins of the evolutionary/Whig version of history, you need to start with the 16th century Indigenous and Spanish debates about the nature of the Americans. I say Indigenous and Spanish debates because a key interlocutor here is el Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, who proffered the model of sophisticated Indigenous cultures like the Inca “tutoring” less sophisticated cultures and bringing them along a developmental path to prepare them for the knowledge of God and the advent of Christianity. His apologetic task is similar to that of Las Casas, but far more personal, and his writing sets up a framework that Las Casas can use. (That’s not from Pagden; that’s from yours truly.)

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: the concept of “civilization” is born of the collision between the cultures of Europe and the cultures of the Americas. It is an American idea.

I wonder if Eric Wolf’s “Europe and the People without History” has anything to say about this? I’ve been wanting to look at that (for my own personal studies). If I ever get a chance to read it (or maybe you’re familiar with it), I’ll be sure to let you know.

“Thus he argued that there was no essential distinction between Indigenous Americans and any other group of people–they simply needed time to develop.”

I do think the geological invention of “deep time” has has profound effects on all theoretical thinking in the social and (especially) physical sciences. Consequently, this assumption of billions (at least for the overall cosmos) and millions of years is why modern evolutionary paleontologists have had to constantly change the datings of their (very few) bone fragments purporting to tell the “out of Africa” scenario (and why I find it led to racist ideas). If their (African humans) history is the “oldest” (the first to develop from the missing link), they should (according to the “equalitarian” idea that there is no “essential distinction” between early African and newer post-African evolved groups), have developed certain technological and conceptual practices way before the more recently-evolved humans (Asian, European, etc.). As a result, some bones have been dated later by these professionals seemingly for ideological reasons (to show that they are not being guided by racist thinking).

This provacative discussion is redolent of Peter Harrison’s account of the ancharonistic usage of “science” (and religion) in the classic texts in the history of science.