Recently, I posed a question for my fellow writers and scholars: if you had to pack a writerly “bug-out bag,” something you could grab in case you had to vacate your home quickly in an emergency, what would you put in it?

This task was much on my mind because I was then faced with the problem of setting aside just one box full of books that I could keep with me throughout this summer of dislocations and relocations. The night before packers came to my home to box up all our earthly possessions and send them to storage, I was assembling a collection of books that I could use throughout the summer to continue my work on my manuscript.

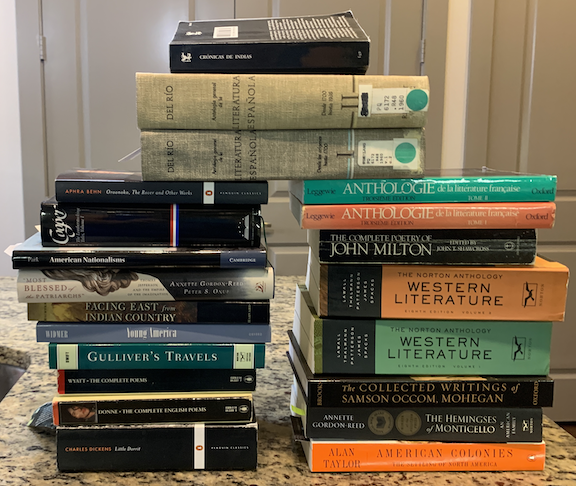

I call this collection my “chapter in a box.” Here are the books I packed:

My “chapter in a box” books. Titles are listed in the post below.

- Mercedes Serna, editor, Crónicas de Indias

- Ángel del Río and Amelia A. de del Río, editors, Antología general de la Literaturea Española, 2 vols.

- Robert Leggewie, editor, Anthologie de la littérature française, 2 vols.

- Aphra Behn, Oroonoko, The Rover and Other Works

- James Fennimore Cooper, The Leatherstocking Tales, Vol. I**

- Benjamin E. Park, American Nationalisms**

- John T. Shawcross, editor, The Complete Poetry of John Milton

- Annette Gordon-Reed and Peter S. Onuf, Most Blessed of the Patriarchs**

- Daniel K. Richter, Facing East from Indian Country

- The Norton Anthology of Western Literature, Eighth ed., 2 vols.

- Edward L. Widmer, Young America**

- Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels

- Thomas Wyatt, The Complete Poems

- Joanna Brooks, editor, The Collected Writings of Samson Occom, Mohegan

- John Donne, The Complete English Poems

- Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello**

- Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit**

- Alan Taylor, American Colonies

There are some titles missing here, clearly. I forgot to grab Montaigne and Rousseau, I don’t have the Quixote here, and my Bevington Shakespeare got loaded into one of God only knows how many book boxes and moved to storage.

Still, this collection of books represents a solid foundation of primary sources for a chapter on ideas of “civilization” from the Early Modern period to the Enlightenment.

The books in this photo are stacked in the reverse order in which they were packed. Thus, I regard Spanish literature, including the literature of conquest, as foundational to the construction of the idea of civilization. A few years ago, I argued on this blog that the first written sources for American intellectual history were and still are written in Spanish, while the deepest founts of American thought are Indigenous in origin. We can write no history of American thought from its beginnings without delving into Spanish sources and Native narratives.

So I must live up to my own expectations here.

In the midst of a whirl of activity that shows no signs of abating for the better part of a year, I have managed so far to read the Spanish literary anthology all the way up to La Celestina. At that point, I switched to the anthology of chronicles of “the Indies” to bring myself up to the same era but via the writings of the “discoverers” and colonizers of the “New World.” (I know we had this discussion on the blog before, but having read these sources in Spanish anew I find it interesting that Columbus did not describe his work as that of “discovery” until his fourth and final letter to the Catholic Monarchs, and that was primarily in connection to his navigational theory that the earth was pear-shaped, a theory widely mocked by map-makers in his own time.)

An interesting point that has emerged so far from my reading is what strikes me as a very early use of the term “pacification.” For instance, in his second report to the Spanish Crown, Hernán Cortés apologized for not having written at length sooner, giving as an excuse the fact that he was “ocupado en la conquista y pacificación de esta tierra”—“occupied in the conquest and pacification of this land.” The word as he used it there seems to have changed very little in meaning up to the present day, so that if Cortés had heard talk of the “pacification” of the Vietnamese countryside, he would have understood both the goal and the methods of the effort. This is hardly a novel insight on my part; historians of colonialism and conquest must have made this point many times over. Without access to JSTOR and/or an academic library, it’s hard for me to give the idea proper attribution, but it is surely not original with me.

I asked a colleague of mine who translates from Spanish to English if this was the earliest use of the term “pacification,” or if it had been part of the language of the Reconquista in relation to the Moorish population of Spain. My colleague, Dr. George Henson, identified the earliest use, from 1422, in an anonymous source discussing “the pacification of the neighbors of Escalona,” a village in the northern part of the province of Toledo. So this term as an abstract noun describing an action does indeed date from the Reconquista period, though as Dr. Henson points out, these abstract nouns derived from Latin are Renaissance terms that entered the Romance languages and English at about the same time.

If only I had access to the OED at the moment to identify the very first use of “pacification” in English! My compact OED—the single greatest reason to join the Book of the Month Club—is languishing in a warehouse with my other books. The best I can do now in my long liminial lounging is Merriam-Webster online, which indeed identifies the first use of the term as occurring in the 15th century.

Thus Europeans had some idea of “pacification” before they encountered a whole New World to “pacify.” Whatever the meaning of that term had been prior to 1492, did it take on ethnic or racial as well as religious or military overtones? What is the connection between “pacification” and “civilization” as nouns describing a process?

Scout says, “What books go in YOUR chapter-in-a-box? Also, can I have a treat?”

I don’t know yet. But I aim to find out.

If a kind reader who does currently have access to the OED would care to comment on the usage of “pacification” and “civilization” in English, that would be wonderful.

And if anyone would care to share what they would pack in their own “chapter in a box,” that would be wonderful as well.

In the meantime, I’m going to finish reading Cortés and then switch back to La Celestina

, which ought to be read—as all literature ought to be read—in relation to its historical context. My poor New Critical professors are rolling in their graves, I’m sure. Just wait until I get to the historical context of the 1980s!

__

**for the next chapter, but in the mix now for variety

5 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I possibly have online access to the OED in more than one way (I rarely use it, I must confess), but I chose to access it via the online resources of my local public library.

OED gives first use of “pacification” in English (is it Middle English, whatever) as follows:

“1437 in H. Nicolas Proc. & Ordinances Privy Council (1835) V. 64 (MED) Þe general counceil..was gedered..for extirpacion of herresies, pacificacion of reaumes & princes, and reformacion of maneres exhorbitantz.”

“Reformacion of maneres exhorbitantz” — what the **** are exorbitant manners? My paperback Merriam-Webster defines “exorbitant” as “exceeding what is usual or proper” (these days I think the word is used mostly in relation to prices). Anyway, neither here nor there.

Sorry, no time right now to do “civilization.” Will try to do that tomorrow unless someone comes in with it first.

Don’t know offhand what I would put in my “chapter in a box.” Not writing much of anything at the moment (except something that I’m writing for myself, not for circulation of any kind).

Btw, a quick run through Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality, might be indicated, including the passage about “the Carib” who (according to R’s source) lacks foresight to such an extent that he sells his cotton bed in the morning and then comes weeping to buy it back in the evening so he has something to sleep on.

Hi Louis, thanks for this. No need for you to do “civilization” — that lexical history in English I know. “Civilization” shows up in English almost two centuries after “pacification.” My surmise is that this holds true across the board for the key powers of colonization in Western Europe, but that i’ll need to check. It is of interest that “pacification” comes first.

At one point in Cortés’s relación to the court, he is contrasting the manners of “los naturales” (natives) with those of Spaniards and other Europeans. But the term “civilized peoples” does not yet exist in Spanish, apparently, so the term he uses is “gente de razón”—rational people, people of reason, sensible people.

The earliest decades of conquest and colonization were proceeding apace without that catch-all word for how the Spaniards and others saw themselves. They were “cristianos,” or “católicos,” not yet “europeanos.” They were “gente de razón,” not yet “gente civilizadas.”

My hypothesis is that “civilization” is born of the New World, not the Old World, and born in the crucible of conquest. But after more reading, we shall see.

Interesting, thanks.

P.s. re “pacificacion of reaumes and princes”

“reaumes” presumably is kingdoms (Fr. royaumes) or maybe realms (?).

I didn’t go down that far in the entry, but maybe there is some further explanation.

For your hatchet job on the Schlafly’s and by extension, Father Stephen Dunker c.m.:

M indszenty Group

Hos 4,0 0 0 Units

Kansas City, Mo. — Father

Stephen Dunker, C. M., chairman and spiritual director of

the’ Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation, has withdrawn from the

posts to devote full time to the

Vincentian Foreign Mission Society, in St. Louis. No successor

has been named.

In the past three years, the

organization, which was formed

in St. Louis in 1959 to combat

Communism “with knowledge

and facts,” has seen the formation of more than 3,000 Cardinal

Mindszenty study groups and

many seminars for the public

and for schools.

The foundation’s weekly radio

program called “Dangers of

Apathy” is now broadcast in 10

major cities from coast to coast.

A monthiy release has a growing circulation and, through

pubiication in Catholic and secuiar newspapers, has reached in

a single month an audience of

4,000,000.