The Book

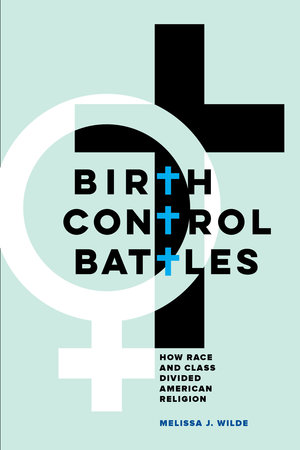

Birth Control Battles: How Race and Class Divided American Religion (University of California Press, 2019).

The Author(s)

Melissa J. Wilde

Women’s reproductive rights are often centered in current conversations about access to birth control, especially by progressive religious activists. Advocates for birth control frequently contend that women should have the ability to choose if and when they want children. Yet concern about women’s rights had little, if anything, to do with early debates over legalizing birth control in the 1930s. Instead, as sociologist Melissa J. Wilde asserts in Birth Control Battles: How Race and Class Divided American Religion, decisions to support legalizing access to birth control had more to do with “whether [religious groups] were believers in the white supremacist eugenics movement and thus deeply concerned about reducing some (undesirable) people’s fertility rates” (1-2). Utilizing examinations of thirty-one denominations, Wilde posits that theology did not influence their decisions to support, refute, or remain silent about birth control legalization (23). Instead, it was these groups’ relationships with white supremacist ideologies that drove their decisions.

Wilde refers to her research method as “comparative-historical sociology,” which attempts to “examine history as systematically as possible” (5). Further, she utilizes a “complex religion” argument that contends that “religion is part and parcel of racial, ethnic, class, and gender inequality” (4). These frameworks provide complicated reasons for why some groups liberalized, some unofficially supported, and some avoided comment on birth control legislation (5). Primarily dependent upon published religious periodicals, Wilde heeds religious leaders’ publicized words. She examines how debates over the social gospel as well as fundamentalist/modernist perspectives influenced groups’ posture on birth control legalization.

Considering the breadth of research and the number of religious groups being analyzed, these arguments could potentially become confusing. Fortunately, Wilde includes extensive charts and maps to ensure that readers understand each group’s alignments, regions, and changes over time. Separating the book into three parts, Wilde analyzes shifts in denominational beliefs about birth control legalization, placing emphasis on nine “‘focus’ years,” beginning with 1926 as a baseline and examining how debates extended into the 1960s (22). She traces developments of denominational interpretations and ends with current discussions about birth control, including Hobby Lobby’s recent refusal to provide employees access to specific contraceptives. Wilde contends that these stories are more complicated than people, particularly religious progressives, might think.

In the early portions of the book, Wilde outlines religious groups’ concerns about “race suicide” and how their support for eugenics and for “[breeding] better humans” undergirded their support for birth control legalization (58, 66). For Protestants who liberalized on birth control, particularly those in the north, the category of better humans excluded Catholic or Jewish immigrants (71). They saw birth control as “essential to eliminating the reproduction of poverty,” which they held new immigrants responsible for, as well as a method for maintaining political power (101, 121). Further, Wilde examines how liberalizers’ concerns about “poverty, war, and social injustice” led to their support of birth control because it meant limiting the reproduction of impoverished, oppressed peoples—groups they saw as inferior (97).

Just as denominational ties influenced support for birth control legalization, Wilde asserts that regional ties also played a role. In particular southerners, though certainly “devoted to eugenics in relationship to blacks,” did not believe in “race suicide,” and saw white immigrants as “potentially adding to the white genetic ‘lifestream,’ rather than destroying their racial stock” (140, 147, 141). They were among several critics. Some denominations were not concerned with the social gospel and did not believe that they had a religious duty to promote birth control legalization, or any other measures outside of the spiritual realm. Other denominations found that those with liberalized views on birth control were working “under the guise of welfare work” in order to limit the reproduction of working class and poor people “all over the country” (133). Though critics differed in their beliefs, Wilde notes that they all concluded that “birth control reform did not make sense racially or religiously” (152). Legalization would not have their support.

Separate from supporters and critics were those who remained silent about birth control. Wilde contends that this silence was not out of “apathy” but because they could not promote birth control for the same reasons as their “fellow religious activists” (155). These silent groups, like the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc., questioned eugenic thought and were critical of “racist thinking in general” (180, 161). Thus, they could not throw their support behind efforts to legalize birth control; they knew activists’ support meant the eventual elimination of those they deemed non-white and unamerican. While silent parties often believed in “the importance of progressive religious activism,” they could not work for a progressive agenda that subscribed to white supremacist ideologies (168). They deemed it prudent to say nothing.

Yet, readers are left wondering if there are deeper implications to this silence. Though Wilde concedes early on that this examination is “not to say that theology plays no role in the explanation that follows,” little theological analysis is provided (12). These silent groups repeatedly emphasized “the love of God and social justice” and declared that they must “take Christ and His gospel of love seriously” (166, 168). They would likely contend that theology, perhaps even more than progressive religious activism, motivated their silence. Animated by the gospel and their belief in a compassionate, just God, they remained silent on birth control and continued other social justice efforts. While theology deserves further reckoning here, Wilde’s thorough research and analysis remain convincing.

By the 1960s, many of these denominations “reluctantly [converted]” to become supporters of contraception, though they originally rejected or were disconnected from first wave birth control activism (198). For some, this meant reframing the argument and focusing on their own parishioners’ use of contraceptives rather than encouraging birth control use for others. By placing the focus on their own constituents, they could adopt this platform without supporting eugenics. Though the research is exhaustive and extensive, Wilde’s organizational methods and explicit explanations enable readers to follow her assertions. Readers can come away from the work understanding that progressive and conservative thought have not always existed monolithically, that religiously motivated political activism is complex, and that historical perspectives remain important in understanding current political conversations.

About the Reviewer

Allie Roberts is a graduate student in the history department at Baylor University.

0