Editor's Note

As part of our #USIH2020-#USIH2021 publications, today we’re proud to share a paper by Wendy Wong Schirmer (Temple University). Check out our full #USIH2020-#USIH2021 conference program and updates here.

“John Jay,” Gilbert Stuart, 1794, National Gallery of Art

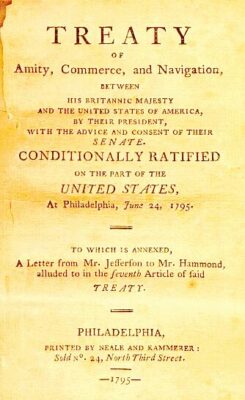

In a union with slaveholders, public clamor about foreign relations could raise divisive questions about the compatibility of slavery and republican government that affected different quarters of that union differently. On April 15, 1794, President George Washington appointed John Jay as envoy extraordinary to London to negotiate a treaty of amity and commerce. Anglo-American relations had been tense since the Treaty of Paris in 1783, and the officially neutral United States struggled to steer clear of the Anglo-French War that embroiled the Atlantic World.

The American Revolution had been won, but the need for the Jay Treaty arose from mutual violations of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which concluded the War for Independence. Britain contended that mistreatment of Loyalists returning to America to regain their estates and the refusal of many states to remove legal impediments to the collection of prewar debts constituted a breach of the peace. Americans retorted that British subjects “abducted” American property in slaves, and continued to occupy the northwestern posts. The United States demanded evacuation of the northwestern posts, but the Articles of Confederation could not compel obedience from the states regarding British debts. In 1785 Prime Minister William Pitt informed U.S. minister in London John Adams that Britain would remain in the northwest unless America paid up. Britain also excluded U.S. ships from the carrying trade to the British West Indies. The July 2, 1783 Orders in Council had forced American produce to enter the islands only in British or colonial bottoms, which Americans deemed deliberately hostile to their ability to carry American goods in American bottoms to every port in the Empire. The November 6, 1793 Orders in Council ignored prior international practice by rejecting the rights of neutrals to carry peaceful cargo.

Negotiations between Jay and Foreign Secretary William Grenville were cordial. Yet, while preserving peace between the United States and Great Britain, the Jay Treaty proved highly divisive at home. The public brouhaha over the treaty brought together Americans’ concerns over foreign powers (or even their own government) “enslaving” them, as well as over the place and future of chattel slavery in the new republic.

While the Jay Treaty debate is notoriously complex, it’s a topic that affords opportunities for thinking about media, reception, and their larger implications in the body politic. If “political, partisan, social, cultural, sectional, and economic concerns repeatedly forced slavery into politics in unforeseen ways,” foreign relations and the functioning of print media provided some of the catalysts.[1] I am therefore using this S-USIH blog post to highlight aspects of work in progress with which I am still grappling how to connect various pieces more effectively. I suggest that thinking about fears of metaphorical “enslavement” in conjunction with the politics of slavery in the Early Republic provides a useful framework for fleshing out connections between public clamor about foreign relations in the Early Republic and the politics of slavery. Conceptually, I am taking my cue from literary scholar Mary Nyquist’s observation that the intersections of political “slavery” and chattel slavery are a complex, understudied, but “foundational feature” of rights discourse.[2] I therefore present my thoughts more as a preliminary sketch—rather than anything definitive— of my attempt to connect those pieces.

My approach to foreign relations in the case of the Jay Treaty debate is therefore vehicular: instead of emphasizing negotiations between Jay and Grenville, I foreground the issues that foreign relations raised for Americans at home, not just about how to achieve certain ends vis-à-vis other powers, but about the nature and process of republican self-government. In comparison and contrast to earlier scholarship on the Jay Treaty that emphasized international politics and diplomacy, more recent scholarship on the Jay Treaty debate emphasizes the expansion of participatory democracy: public opinion erupted once the treaty was made public, and familiar accounts of treaty opponents burning John Jay in effigy and copies of the treaty roasting over bonfires on the Fourth of July fill letters and print from Boston to Charleston. I thereby treat foreign relations as a meeting ground between high politics and the further development of popular politics.

Difficulty in discussing slavery as metaphor in relation to the politics of slavery in the Early Republic lies in articulating how they intersected. For the sake of brevity, I concentrate mostly on the anti-treaty, Democratic-Republican side of the debate. Anti-treaty Republicans often attacked the secrecy surrounding the treaty with words such as “slavery” and “despotism.” Moreover, what Jay was and was not able to secure for the United States contested slavery in the union and threatened Southern slaveholders. What connects raucous public commentary and outcry with the slavery issue not long after Jay embarked for London in April, 1794 until the end of April, 1796 was a combination of medium, message, and meaning: the press and its function, the rhetoric Americans used to decry secrecy, and the wider implications of the treaty’s contents when finally revealed in a scoop by Benjamin Franklin Bache, editor of the Philadelphia Aurora—a leading anti-treaty and Democratic-Republican voice.

In the Early Republic, media had a function as well as conveyed particular messages. An antidote to secrecy, print—and the print exposé— played an important role in shaping public opinion in the Early Republic. At a time of diplomatic and domestic crisis, the exposé constituted a site of what philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre has called “rights, protest, and unmasking.”[3] Newspaper editors such as Bache saw the purpose of their medium as “diffus[ing] light within the sphere of its influence – dispel the shades of ignorance, and gloom of error, and thus tend to strengthen the fair fabric of freedom on its surest foundation, publicity and information.” Republican anti-treaty discourse often took the form of unmasking and protesting violations of the people’s rights. Outraged treaty opponents complained of a lack of transparency: they howled that Jay had left the United States “supine,” fearing that Britain deemed Americans too weak and ignorant to defend their rights. That the Senate debate over the treaty took place behind closed doors meant that the Washington Administration intended that the treaty’s contents—however suspicious—would be rammed down unsuspecting Americans’ throats. Moreover, the role of Washington’s popularity in getting the treaty signed raised concerns that the President was a monarch in disguise, and Americans were thus meant to labor under the Constitution “like slaves.”[4]

In the Early Republic, media had a function as well as conveyed particular messages. An antidote to secrecy, print—and the print exposé— played an important role in shaping public opinion in the Early Republic. At a time of diplomatic and domestic crisis, the exposé constituted a site of what philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre has called “rights, protest, and unmasking.”[3] Newspaper editors such as Bache saw the purpose of their medium as “diffus[ing] light within the sphere of its influence – dispel the shades of ignorance, and gloom of error, and thus tend to strengthen the fair fabric of freedom on its surest foundation, publicity and information.” Republican anti-treaty discourse often took the form of unmasking and protesting violations of the people’s rights. Outraged treaty opponents complained of a lack of transparency: they howled that Jay had left the United States “supine,” fearing that Britain deemed Americans too weak and ignorant to defend their rights. That the Senate debate over the treaty took place behind closed doors meant that the Washington Administration intended that the treaty’s contents—however suspicious—would be rammed down unsuspecting Americans’ throats. Moreover, the role of Washington’s popularity in getting the treaty signed raised concerns that the President was a monarch in disguise, and Americans were thus meant to labor under the Constitution “like slaves.”[4]

Rhetorically, print discourse used metaphorical “slavery” either explicitly, or alluded to it through adjacent words like “despotism” and “tyranny.” Tyranny and despotism in Americans’ moral and political imagination killed republics everywhere, leading to “slavery”—and they long got the message that this was the fate that awaited all who failed to govern themselves. Before, during, and after the Revolution, the use of “slavery” as a metaphor had ties of association with chattel slavery. Colonists and then Americans complained about being “driven like negroes” whenever they felt “tyrannized,” which had prompted Samuel Johnson’s famous quip in Taxation No Tyranny (1775) about “[hearing] the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes.” Far from trivial, mention of the word, even if slight, signaled a text’s emotional highpoint, even if seemingly absurd or hypocritical to modern ears. The enslaved, both in the Empire and in the new republic, stood outside of civil society. They were also unable to exercise political autonomy, were subject to arbitrary power, and thus enslaved individuals—and nations—were the opposite of independent.[5]

Fears of enslavement by a foreign power reverberated within a union with slaveholders regarding trade and the understanding of the law governing slavery. George Van Cleve has called it a “slaveholders’ union”—“a union where protection of slavery was an integral part of law and government.”[6] To “govern the United States was to govern slavery, as John Craig Hammond puts it, “and governing slavery always entailed political conflict.”[7] And Jay’s Treaty challenged that governance of slavery. When Bache’s Aurora published the contents of the treaty in full and without warning on June 29, 1795, Southern slaveholders could not but notice how the Jay Treaty threatened slavery in various ways. Article 12 was a bone of contention. It limited access to the British West Indies to ships of seventy tons or less. It permitted U.S. ships of seventy tons or less to trade with the West Indies but prohibited re-exportation from U.S. territory of molasses, sugar, coffee, cocoa, and cotton, whether or not they were the products of the British West Indies. Americans profited from a considerable re-export trade that brought these products to the United States to be shipped to France and the rest of Europe. Article 12 would effectively kill the re-export trade in these products of slave labor, and prematurely halt the growing export trade in cotton significant to Georgia and South Carolina.

In addition, the Jay Treaty failed to address compensation for enslaved people freed by the British after the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1783). Refusing American claims for compensation, the British interpretation of the treaty was that its stipulations applied only to those who fled to British lines after the signing of the treaty, and that those already promised freedom could not be re-enslaved. American slaveholders demanding compensation argued that enslaved people who claimed British protection after the signing of the treaty were still slaves because they had not yet been carried beyond the borders of the United States. When Jay wrote to Secretary of State Edmund Randolph from London that he and Grenville “couldn’t agree about the negroes,” he remarked that he did not see it as worth breaking up negotiations. Randolph warned that if Jay failed to mention them at all, certain parts of the Union would feel aggrieved. The issue of enslaved people carried away by the British provoked strong protest in the House of Representatives from early March 1796 to the end of April 1796. Republicans strongly asserted that the terms of the 1783 peace treaty intended the slaves to be left behind: Britain had violated the terms of the treaty first. In the House, James Madison argued that until the Jay mission, Britain had openly recognized the justice of American demands. The Aurora also claimed that if Southern slaves had not been carried off, they could have been used to repay British debts—an argument Thomas Jefferson also made in 1792.[8] For slaveholders, dismissing compensation for slaves would mean subordinating American independence to British readings of law regarding slavery, which opponents of slavery also utilized in order to make their antislavery claims.[9]

Attending how use of “slavery” as metaphor intersected with the international and national politics of slavery through print media allows us to view the Jay Treaty debate in terms Americans grappling with the unfinished business of revolution. Whatever peace Jay had secured between Britain and the United States that was supposed to help secure American independence abroad, alarmed voices at home such as those appearing in the Charleston City Gazette expressed a desire to “get rid of the most infamous of all infamous treaties—of Mr. Jay’s manacles, of his fetters, of his shackles!” [10] In addition, response to the publicized squabbling and newspaper battles over the Treaty revealed the strength of a Southern voting bloc: Southern slaveholders typically presented a united front when they sensed an external threat to their ability to control and govern their human “property.” Slaveholders could imagine themselves “enslaved” by a treaty with a monarchical power that marginalized their interests, and a federal government that itself threatened to backslide into “monarchy.” The Jay Treaty debate and the manner in which it unfolded reminds us of the ways slavery affected everything it touched, to more and lesser degrees. Foreign relations, if not diplomatic crises, presented Americans with a confluence of language, ideology, and politics that served to highlight the various ways in which it could.

[1] John Craig Hammond and Matthew Mason, “Introduction: Slavery, Sectionalism, and Politics in the Early American Republic,” Matthew Mason and John Craig Hammond, eds., Contesting Slavery: The Politics of Bondage and Freedom in the New American Nation (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011), 1-8.

[2] Mary Nyquist, Arbitrary Rule?: Slavery, Tyranny, and the Power of Life and Death (University of Chicago Press, 2013), 4.

[3] For some scholarship on the diplomatic negotiations surrounding the Jay Treaty, see Charles R. Ritcheson, Aftermath of Revolution: British Policy towards the United States, 1783-1795 (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1969); Jerald Combs, Jay’s Treaty: Political Battleground of the Founding Fathers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970); Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990). For scholarship emphasizing print and democratic participation see Donald H. Stewart, The Opposition Press of the Federalist Period (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1969); James Tagg, Benjamin Franklin Bache and the Philadelphia Aurora (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991); David Waldstreicher, In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776-1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997); Jeffrey L. Pasley, “The Tyranny of Printers”: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002); Todd Estes, The Jay Treaty Debate, Public Opinion, and the Evolution of American Political Culture (Amherst: University of Masschusetts Press, 2008); for a systematic treatment of secrecy that mentions the Jay Treaty within its framework, see Katlyn Marie Carter, “Denouncing Secrecy and Defining Democracy in the Early American Republic,” Journal of the Early Republic, 40.3 (Fall, 2020): 409-433, especially 427-430; Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984), 68.

[4] Aurora and General Advertiser (Philadelphia, PA), November 8, 1794; Aurora Jun. 16, 1795; “Atticus,” Independent Chronicle (Boston, MA), Sep. 3, 1795, reprinted in the Aurora (Philadelphia, PA), Sep. 12, 1795.

[5] Samuel Johnson, Taxation No Tyranny (London: 1775); for work on slavery as metaphor, see Patricia Bradley, Slavery, Propaganda, and the American Revolution (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999) 22; Peter A. Dorsey, Common Bondage: Slavery as Metaphor in Revolutionary America (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2009), specifically xvi. For a discussion of how the patriot cause linked British tyranny to fears about violent Indians and slave insurrection, see Robert G. Parkinson, The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

[6] George William Van Cleve, “Founding a Slaveholders’ Union, 1770-1797” in Matthew Mason and John Craig Hammond, eds., Contesting Slavery: The Politics of Bondage and Freedom in the New American Nation (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011), 118.

[7] John Craig Hammond, “Race, Slavery, Sectional Conflict, and National Politics, 1770-1820” in Jonathan Daniel Wells, ed., The Routledge History of Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Routledge, 2018), 20.

[8] John Jay to Edmund Randolph, September 13, 1794, Feb. 6, 1795, in Lowrie and Clarke, American State Papers: Foreign Relations, 1: 485, 518; Edmund Randolph to John Jay, Dec. 3, 1794, Ibid., 509.

[9] Frederic Austin Ogg, “Jay’s Treaty and Slavery Interests,” Annual Report of the American Historical Association, 1901, 1:291-292; James Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2014), 121-25, 128, 187 fn22; Eliga H. Gould, Among the Powers of the Earth: The American Revolution and the Making of a New World Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 162-64.

[10] “To Messeurs Freneau and Paine,” City Gazette (Charleston, SC), Oct. 28, 1795.

0