I’m wrapping up a chapter on what the term “civilization” meant during the Revolutionary Era and in the Early Republic. My primary sources are not multitudinous, but they’re representative: Voltaire, Gibbon, Jefferson, Adams, Equiano, Washington, various appearances of the concept/term in the Gazette of the United States. (Suggestions for additional sources welcome!)

This chapter goes from the mid-18th century to the founding of the University of Virginia, which is a nice place to leave things: Thomas Jefferson wanted all the students to learn Old English and study Anglo-Saxon civilization. (I have a piece about “Anglo-Saxonism” that should be coming out in the Washington Post “Made By History” section on Monday. I will not be reading the comments.)

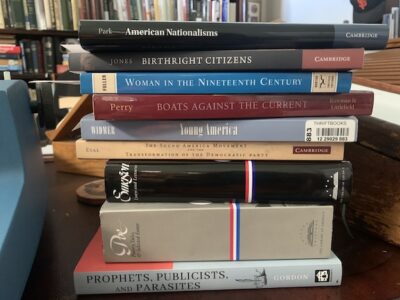

Some sources for the next chapter.

Initially, I thought that the next chapter should cover 1820 to the end of Reconstruction. That’s a long span. It seems to me that, for this project—which is now, thankfully, a history of the idea of “Western Civilization”—the chapter breaks should only come where there is a distinctive development or shift in the meaning of the concept under scrutiny. If I were to break it somewhere, it would probably be the U.S. / Mexico war. I can see a shift in American thought here. “Civilizing the west” and Manifest Destiny include a vision of one kind of “western civilization” that looks toward the Pacific and even across the Pacific to the “markets” of Japan and China. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the geopolitical stakes of the Crimean War mark a moment when, for Americans, “western civilization” is an object of thought that comes into view when looking across the Atlantic and deciding which powers in Europe were part of civilization and which were not.

My hesitancy to break the chapter in two is partly due to the potential narrative arc provided by one of my key primary sources for this longer periodization: the various editions of George Bancroft’s history. The first volume of the first edition appeared in the mid 1830s, while the last edition revised by Bancroft himself was published in the mid-1880s. By looking at major stages of Bancroft’s ongoing project—the first edition, the centennial edition, the “author’s final revision,” it will theoretically be possible to track subtle changes to the meaning of “civilization” or even note the rise of the term “western civilization,” should it appear anywhere in these volumes.

However, that’s assuming that Bancroft’s thinking or writing over that span of many decades reflected or refracted these shifts in thought that are easily visible elsewhere. Maybe Bancroft was a hidebound monomaniac who never entertained a single new idea between 1830 and 1885. I don’t know yet, because I have never read him; I have only read about him.

But I’m fixing to find out. En route to my home is about twelve hundred dollars’ worth of George Bancroft: the first edition, an edition from 1851, an edition from 1855, the centennial edition, and the final revision. This may turn out to be a really bad bet on my part. What if George Bancroft is of absolutely no use to me at all?

For anyone saying, “You can read him online”… I cannot. I can’t read anything online longer than a blog post or a magazine article. Can’t focus, and can’t retain or process anything I’m reading. I could download .pdfs of various scattered volumes of Bancroft and print them out, but it’s actually cheaper to buy the originals than it would be to print the .pdfs. And traveling to special collections around the country to read Bancroft on the page would also cost more than just buying the books—if special collections were even open yet.

Am I trying hard to justify to myself this extravagant and frankly unhinged pandemic purchase by insisting that there was just no other way to access this text? Absolutely. Is it working? Nope. I am out of a job come mid-May, and here I am buying books like I am made of money AND have empty shelf space. (I am not and I do not.)

But I can say this: after that kind of outlay, George Bancroft is damn sure going to be of use to me. I just don’t quite know how yet.

0