Editor's Note

The views expressed in this blog post do not reflect the views of the blogger’s employer.

Since returning to my home state last March and taking up a position at the State Historical Society of Iowa (SHSI), I’ve frequently thought about the role of state history in broader historiographical conversations. State history finds itself sandwiched between larger historiographical conversations at regional, national, and international levels and those at the level of local history. Those of us working in state history often have opportunities to tell diverse stories, yet our state-specific focus can limit what histories we tell.

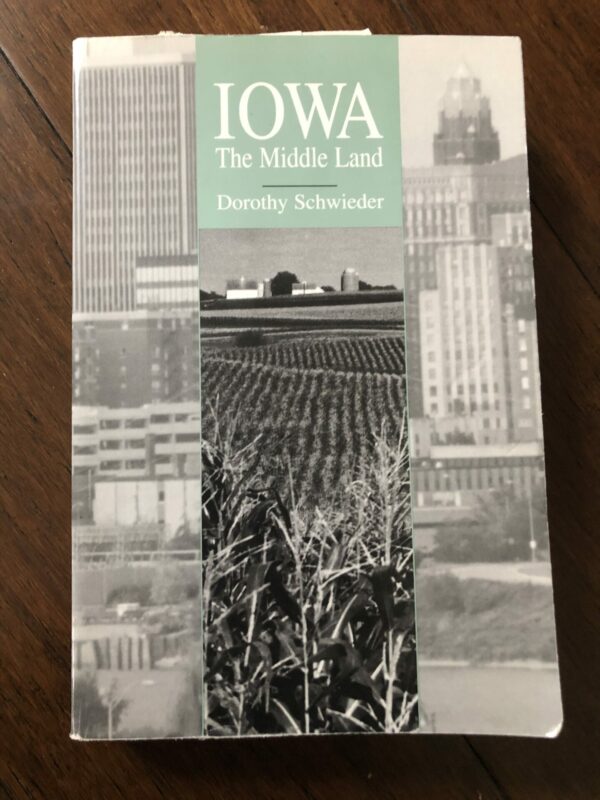

Earlier this month, I hosted (virtually, of course) the State Historical Society of Iowa’s first Iowa History Book Club. The conversation focused on an absolute classic in Iowa history—Dorothy Schwieder’s Iowa: The Middle Land. The book itself is a mainstay in Iowa history, even 25 years after its publication.

My recent return to Schwieder’s work reminded me of state history’s peculiar position. In the book, published in 1996, Schwieder engages with several historiographical developments.

Most broadly, Schwieder writes a sweeping social and cultural history of Iowa, which was notable at the time. She tells the stories of everyday people. Readers encounter the history of men, women, Native Americans, immigrants, Black migrants, Asian refugees, and a host of others who made Iowa their home. Historiographically, this book reflects the turn toward social and cultural history that had been taking place in the broader field at the time. Schwieder acknowledges her place in this turn. In very intentional and explicit ways, her state history engaged with methodological and historiographical interventions taking place throughout the field and applied them in Iowa.

Alongside this connection to broader historiographical developments, Schwieder’s work also self-consciously built on a long legacy of Iowa history. She acknowledged the influence of major figures in the field, such as the founder of the SHSI Benjamin Shambaugh, and she also conceptualized her work within a broader, state-specific program outlined by one of her predecessors, Leland Sage. In the mid-1970s, Sage had laid out an ambitious program for revitalizing and expanding the field of Iowa history, and in no uncertain terms, Schwieder understood her work to be a contribution to that broader program. This is to say that her project was also tied to an intellectual and historical tradition rooted in Iowa specifically.

Schwieder, a longtime professor of history at Iowa State University, would be on the Mount Rushmore of Iowa historians (if such a monument existed). Through her scholarship and mentorship, she shaped generations of historians working on Iowa and the Midwest. For decades, Schwieder was the undisputed dean (or as some referred to her, the den mother) of Iowa history. Even seven years after her death, she towers over the field.

Despite this, Schwieder acknowledged that state history could be a hard sell in academic history circles. When she started her work in state history in 1970, many of her colleagues in the history department at Iowa State looked down their noses at the subject, seeming to buy into ideas that “state history had little value for professionals” or that it was “only for untrained historians who enjoyed researching local or minor topics with little broader importance.”[1] Despite the naysayers, she remarked that serendipitously a Texan chaired her department, and like all proud Texans, he didn’t need any convincing that state history mattered.

Schwieder’s experience with her chair reflects my own years of living in Texas. In the Lone Star State, there is little doubt that state history matters and that Texas historians can produce serious, impactful and broadly interesting scholarship.

My return to Schwieder’s work earlier this month brought to the fore the question of the role of state history in broader historical conversations. It may be because of my five-year sojourn in Texas, my role at the SHSI, or my engagement with the brilliant scholars working on Iowa history, but I don’t need to be convinced that state history can make broad and significant contributions.

In the field of intellectual history, I continue to think about what such contributions look like, especially given that ideas have little respect for state boundaries. In Iowa history, for instance, there is a clear intellectual tradition that begins with scholars like Benjamin Shambaugh and continues through to historians like Schwieder. There’s also a long and storied record of scholarly history in journals like the one I edit, The Annals of Iowa. Other states have similar state-specific intellectual legacies.

Yet, there are also trickier questions. Like what role did Iowa and Iowans play in the ideas and beliefs of Iowans like Carrie Chapman Catt, Henry A. Wallace, or Norman Borlaug? How were the ideas of men and women who spent formative years in the state, such as scientist George Washington Carver or historian Glenda Riley, influenced by their time in Iowa?

These are complicated questions, but they are also questions that can be richly queried by state historians. In some ways, state historians are uniquely positioned to explore these questions.

For instance, how was the Iowa Supreme Court’s landmark (and unanimous) 2009 decision to legalize same-sex marriage influenced by the Court’s specific legacy of being at the forefront of civil rights? This decision made Iowa only the third state to recognize same-sex marriage, the first to do so outside of New England, and the first to do so with a unanimous ruling. To many outside of Iowa, the decision was surprising, but the state’s Supreme Court has a long history of rulings that make the 2009 ruling far less unsuspected. The Iowa Court’s rulings to integrate schools (1868), allow women to practice law (1869), ban discrimination in public accommodations (1873) and desegregate lunch counters (1949) often predated similar decisions by the US Supreme Court by several decades. The 2009 decision on same-sex marriage fit this well-established pattern. Without a rich understanding of Iowa’s history, though, a key ideological through line that contextualizes this decision would be lost.

Dorothy Schwieder was a trailblazing historian. The first woman appointed to the history faculty at Iowa State, the first woman to earn the rank of full professor in the department, and the only history faculty member to earn the rare honor of being named a University Professor. Her work is careful, thoughtful, and engaged in ways that make state history shine. It also allows us to ask these bigger questions about how a deep knowledge of a place and the people and ideas who shaped it might provide insights that help us understand histories that extend far beyond a state’s borders.

0