The 1619 Project is, among other things, a hypervisible illustration of the ways that activism and scholarship are affecting one another in the era of Black Lives Matter. The debate among historians about this intersection has been both interesting and painful to watch, as members of the profession line up in two opposing camps.

One camp insists that activism has hijacked scholarship on race and racism, stretching the existing evidence into grotesque shapes to accommodate a simplistic and sinister vision of the American past that reads more easily as a demand for change. Bulldozing the irony and tragedy of the nation’s history, the BLM-inspired historians will not present the whole story because it will rob their case for activism of an uncomplicated historical mandate—that, essentially, is the argument coming from this camp.

The other camp counters that the relationship between scholarship and activism has in fact been far more mutual: it would be disingenuous to deny that the protests of our moment have inspired historians as they research and write, but—this second camp argues—this inspiration comes from the undeniable parallels and continuities to be found in the history of Black protest and resistance. Furthermore, scholarship has itself been an inspiration and a resource for activists; rather than a junior or subordinate partner, academics have created both broad analytical paradigms as well as more specific case studies for thinking through the dynamics and manifestations of racism that have been widely influential and have helped determine the shape that protest takes. Scholars are not taking dictation from the movement nor are they trimming their histories to fit its propagandistic needs.

The most straightforward articulation of the first camp that I have seen was published recently by Daryl Michael Scott in the new journal Liberties

, which is edited by the ex-New Republic writer and editor Leon Wieseltier.[1] Scott has coined the term “thirteentherism” to designate a kind of conspiracy theory that was, he says, incubated among prison abolitionists but that has now infected much of the scholarship on race and prisons since the Civil War.

In brief, “thirteentherism” is the idea that forms of penal labor—especially the post-Reconstruction practice of convict leasing in the South—have amounted to a second form of slavery, and that this outcome was planned and intended when the Thirteenth Amendment was drafted—thus the exception clause, “except as a punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” This idea has led some activists to agitate for the repeal of the Thirteenth Amendment along with its replacement: a new anti-slavery amendment that does not have the exception clause. But while some people—it is questionable whether someone like Kanye West is properly labeled as an “activist,” much less a scholar—have articulated that desire for a repeal-and-replace deal, Scott insinuates that historians who have written about convict leasing also identify this as a goal and have adjusted their histories to support the effort. (He’s not remotely correct.)

Scott was also interviewed in The Chronicle of Higher Education, expanding upon his thoughts about activist scholarship and its prioritization of political convenience and correctness over truth and accuracy. “[I]f a lie will set you free, they will take the lie,” he states.

[I’ve already unpacked these two pieces on twitter, and if you’re interested, you can read my analysis there (thread 1

and thread 2), as well as the very fact-based rebuttal that Khalil Gibran Muhammad wrote to Scott’s more specific claims about the history of convict leasing.]

In the essay and the interview, Scott takes the epistemological position that lies about history are generally straightforward and unambiguous, while the truth is always complex and rife with irony. Historians who tell their stories in ways that can support activism are therefore immediately suspect: if you are really looking at all the evidence, you’re certain to find many things that will be inconvenient, that will introduce too many qualifications and involutions to be ideologically useful or inspiring.

That is his general perspective, but Scott is also very specific in his comments about the way his skepticism toward the 1619 Project has pushed him toward new research (well, “research”—he doesn’t produce any hard evidence in his essay or in the interview) about the intellectual history of prison abolitionism in the belief that he will find a basis for discrediting what he sees as the fallacious arguments put forward by historians of prisons and policing. He’s hoping to challenge what we know about the new scholarship in order to reestablish the validity of the older scholarship which anti-racist historians have been contesting. The goal is not so much to engage with the new scholarship as to delete its intervention—what I would call reactive revisionism. It is revisionist insomuch as it diagnoses a systematic error within a body of scholarship caused by a worldview held in common by the historians in the community producing that scholarship, but it is reactive (if not objectively reactionary) because the desire is not to move forward to a better understanding of the available evidence but rather to move backward to a previously “settled” consensus.

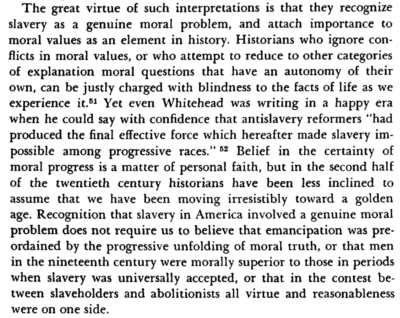

The nature of that former consensus can be characterized generally within a framework most successfully articulated by David Brion Davis: the “problem” paradigm. Here is one of the most important programmatic passages in Davis’s oeuvre, and it defines pretty well the general tenor of this way of viewing both history in general and—perhaps most especially—the history and legacy of African slavery in America.

DBD, Problem of Slavery in Western Culture, page 27

This way of looking at history assumes that, if they are doing the job correctly, the historian will not only find but adeptly convey the moral complexity of the past—its ironies, its tragedies, its ambiguities. It is a way of thinking about human nature that owes much to mid-twentieth-century literary criticism, and, perhaps even more directly, to mid-twentieth-century Christian theology, especially to Reinhold Niebuhr. It is very similar to a mindset that was recently critiqued by Jennifer Wilson, in a review of George Saunders’s new book on “the Russians” (Gogol, Chekhov, et al.); Wilson calls it the “Empathy Industrial Complex.”

To be honest, I have already laid out far too many ideas for me to wrap this post up neatly, so I will postpone trying to do so for a second post. But what I hope to have accomplished here is to have connected one example of the backlash against the 1619 Project to a more general reactive dynamic and to have identified what kind of history it is to which this reaction wishes to return. More later.

Notes

[1] I cannot link to the essay, unfortunately, because Liberties took the essay off-line. This appears to be a standard practice for the purpose of getting people to subscribe to the print version of the journal.

0