Editor's Note

Today’s guest post is by Jeffrey Ludwig, who earned his PhD in history from the University of Rochester in 2015. His dissertation was an intellectual biography of late social critic, Christopher Lasch. He now works at the Seward House Museum as Director of Education. This is the second in a series of two posts relating to William Seward for USIH.

Twice previously for this blog (here and here), I have submitted posts asking whether William Henry Seward (1801-1872) has anything to offer intellectual history. In both, I explored how the former Secretary of State adopted intellectual trappings and deployed intellectuals for foreign policy gains. Another way to consider Seward is an early globalist figure. An apostle of expansion, Seward was also well-travelled, completing four lengthy international journeys during his lifetime including a full circumnavigation of the globe in his retirement. Out of that trip came Seward’s last intellectual act— a sprawling travel narrative, William H. Seward’s Travels Around the World, published posthumously in 1873.

For the majority of Seward’s biographers, his retirement trip and the book it spawned are treated as little more than afterthoughts.[1] This late chapter in Seward’s life has been ignored at their peril, and to the detriment of the field. As historian Jay Sexton argued in 2014: “Both an account of Seward’s world tour and an affirmation of the nationalist principles he promoted throughout his political career, Travels

is a key text in the transnational history of the Civil War era.”[2] Curious, and curiously overlooked, Travels provides a unique source for historians of ideas and globalization.

Travels meant a great deal personally to Seward, who was still tinkering with his nearly-completed manuscript on the day he died. Abandoning in-progress memoirs, he dedicated his final months in the summer and fall of 1872 to recounting his world tour. Seward desperately relied upon his family to help him write; hobbled by injuries from an assassination attempt, he had lost use of both of his arms. Dictating his memories and sprinkling in “philosophical” ruminations on foreign cultures, Seward expended his last energies to bring Travels forward in an octavo volume of almost 800 pages.[3]

The result was a striking book. Seward’s family negotiated a sumptuously high production value with the New York publishing house D. Appleton and Company, which bore the costs of printing a massive tome with over 200 detailed illustrations and a large trifold map in the appendices.[4] Before his manuscript reached galley form, D. Appleton executives sent word to Seward of “being much pleased with the book” and “confident of a large sale.”[5] They were right. The first run of Travels sold 60,000 copies and netted the Seward estate more than $50,000 in royalties.[6] Seward’s book caused a sensation at a time when few Americans possessed the means to afford international travel. Yet a popular appetite clearly existed. The publication of Seward’s Travels coincided with the release of Jules Verne’s adventure novel, Around the World in 80 Days

, and William Perry Fogg’s serialized Round the World chain of letters printed in major newspapers.[7]

The voyage posed real challenges for the aging Seward. Altogether, over the course of 14 months abroad, he travelled over 44,000 miles. Beginning from his home in Auburn, NY in August 1870, Seward ventured westward, cutting overland across the U.S. via the transcontinental railroad to San Francisco, where he boarded a mail steamer for Japan. From there Seward trekked south through China, down the Straits of Malacca, and into South Asia. Taking another steamer, this time through the Near East, he crossed into Egypt, the Holy Land, Greece, and into the Ottoman Empire. The final leg of his tour brought Seward through Austria-Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, France, Germany, and Great Britain. Seward concluded the trip in October 1871, sailing west across the Atlantic bound for America.

The trip was possible thanks to extraordinary advances in transportation and communication. He took advantage of the U.S. Transcontinental Railroad, transpacific and transatlantic steamship lines, the Suez Canal, and new railways in Japan and India. He kept a map of telegraph lines with him throughout his journey, sending and receiving cables all along the way.[8] For Seward, a lifelong advocate for internal improvements, the modernizing infrastructure seemed as much a vindication as a marvel. “You can buy your ‘through ticket’ in New York,” Seward bragged upon his return, “and go from steamer to railway, and railway to steamer, stopping at ports occasionally, where you will find hotels and tourists, merchants and missionaries, people talking English, and dinners and tea parties.”[9]

Seward viewed his travels through the lens of a man who was at once accustomed to power and invested in empire. Travels reflects the prejudices of its author’s class, gender, race, and era. Passages read like classic examples of Orientalist western text, with Seward exoticsizing otherness, ranking cultures into a hierarchy, and affixing his gaze towards elephant fighting pits, concubinage, and other sights of exploitation. Then too, for a man who staked his career on ending slavery, Travels is full of racism. Disappointing but not surprising. Seward travelled just as social Darwinism was becoming an American vogue. His own publisher, D. Appleton, was its leading source of distribution; likely much of the reason D. Appleton could afford Seward for its catalog owed to the fortune it made selling copies of Darwin and Herbert Spencer.[10]

By the same token, Seward used Travels to denounce the mistreatment of women and to argue for their greater legal autonomy and equality. Touting his own adopted daughter and travel companion, Olive, as an example, he argued for the benefits of educating and elevating women to the highest places in society. Though not always consistently, Seward lamented examples of the “degradation and debasement of women,” criticizing customs that “not only exclude her from society, but render her incapable of it.”[11] Nor did Seward always afford Olive treatment as an equal; for all of her elevation, she spent a good deal of the journey serving as her adopted father’s amanuensis and helpmate, here taking hours of dictation, there cutting his food or assisting with other basic needs.

Ultimately, for Seward’s contemporary readership, his bromides and ruminations probably registered less than the overall thrill-seeking and dramatic portions of his narrative. These were generously apportioned for Victorian audiences. Seward seems to have modeled his prose style for Travels after his favorite novelists, Daniel Defoe and Jonathan Swift. “The best two novels I know of are Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver’s Travels,” he noted from his writer’s desk. “The test of their excellence may be found in the fact that they are equally delightful to the comprehension of a child and the intellect of a sage.”[12]

Seward likely succeeded at his own standards of combining a touch of light narrative with analysis of foreign cultures and economies. Yet, the simple and the profound did not always overlay seamlessly. His attempts to appeal to both the child and the sage often undermined each other. Perhaps the contradictions at the heart of Travels are the most revealing to historians today. Like the juggernaut of American imperialism rising late in Seward’s career, his final book contains multitudes of simplicity and complexity.

William Seward’s globe, courtesy of the Seward House Museum

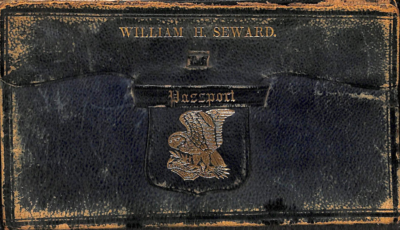

William Seward’s passport, courtesy of the Seward House Museum

[1] Seward’s Travels

, as well as the lengthy 1870-1871 trip that informed it, have been under-considered by his biographers. Of the three most recent full-length biographies of Seward, the saga behind his book have received a sum of 4 pages of out 547 (Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012), 3 out of 310 (John Taylor, William Henry Seward: Lincoln’s Right Hand (New York: HarperCollins, 1991); and 5 out of 566 (Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967). Representative of this cumulative disinterest is Van Deusen’s assessment: “Its historical interest is slight” (563). Likewise, Taylor regards Travels rather coolly as “a lucrative if somewhat shallow literary enterprise” (295). Better attention has more recently been paid by Jay Sexton, who argues that “(t)he significance Seward— the most notable U.S. public figure to that point to complete a world tour— accorded to his travels stands in contrast to scholars’ neglect, if not dismissal of them.” See Jay Sexton, “William H. Seward and the World,” Journal of the Civil War Era 4.3 (September 2014): 398-430.

[2] Sexton, 398.

Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William Seward v. 2 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1900), 524.

[4] Van Deusen, 562.

[5] Frederick Seward to William H. Seward, 30 August 1872 & 4 September 1872. The Seward Papers are archived in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Rush Rhees Library, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York. Many have been digitized: http://www.sewardproject.org/

[6] This from Seward’s friend at D. Appleton & Co, James Derby. See James Derby, Fifty Years Among Authors, Books, and Publishers (New York: G.W. Carleton and Company, 1884), 84.

[7] See Lynne Withey, Grand Tours and Cook’s Tours: A History of Leisure Travel, 1750-1915 (New York: Morrow, 1997), 268-270, and Sexton, 403.

[8] Sexton, 400-401.

[9] This anecdote came from Seward’s “Table Talk” notes, drawn from dinner conversations he had over the years, and in this case from July of 1872. See Frederick W. Seward, Seward at Washington as Senator and Secretary of State: A Memoir of His Life with Selections from His Letters, 1861-1872(New York: Derby and Miller, 1891), 503.

“Appleton dominated the new intellectual movement,” Richard Hofstadter reminds us, “and rose to unchallenged leadership in the publishing world on the tidal wave of evolutionism.” See Hofstadter, Social Darwinism in American Thought (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944), 22-23.

[11] Seward, Travels, 508.

[12] Frederick W. Seward, Seward at Washington, 498.

0