Fifty years ago this month, Curtis Mayfield and a four-piece band appeared at the Greenwich Village nightclub, Paul Colby’s Bitter End. A small room, a small band, an intimate atmosphere. In the recording made of the performance, one hears the sound of the audience by hearing the individual sounds that comprise it—pairs of hands clapping, appreciative shouts, calls out from here and there, “Right on!” “Right on!” When Mayfield speaks to the crowd, his tone is mild, relaxed, conversational. He doesn’t have to raise his voice even when the band continues to play behind him.

At one point, introducing “We’ve Only Just Begun,” a song not associated with him, Mayfield acknowledges the odd choice. “A lot of folks think this particular lyric may not be appropriate for what might be considered underground,’” he says. “But I think underground is whatever your mood or feelings may be at the time so long as it’s the truth.”

“We’ve Only Just Begun” had itself only just begun. It had started as a jingle in a bank commercial a year earlier; currently it was a smash hit for a new group called The Carpenters. This sort of data can be discovered on the internet in a matter of seconds. More difficult to decipher would be what Mayfield meant by the term “underground.” This was an artist who, as principal singer and songwriter for The Impressions, had had numerous hits on the R&B and pop charts for the better part of a decade.

“We’ve Only Just Begun” had itself only just begun. It had started as a jingle in a bank commercial a year earlier; currently it was a smash hit for a new group called The Carpenters. This sort of data can be discovered on the internet in a matter of seconds. More difficult to decipher would be what Mayfield meant by the term “underground.” This was an artist who, as principal singer and songwriter for The Impressions, had had numerous hits on the R&B and pop charts for the better part of a decade.

But these matters don’t necessarily play into the feeling I have when I hear those scattered shouts of “Right on!” and when I hear the particular pronunciation Mayfield gives to the phrase so long as it’s the truth. The specificity of these aural artifacts transports me not only into the room but into the political-cultural moment. It may be the closest thing to time travel that I’m able to know.

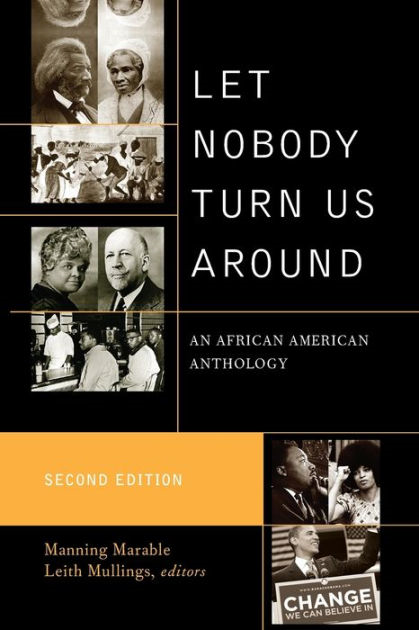

In his anthology of African American social and political thought, Let Nobody Turn Us Around (2009), Manning Marable divides the Black Freedom movement of 1955-1975 into two roughly decade-long phases: “the campaign for desegregation and the struggle for Black Power” (352). Mayfield has a presence in both phases. His hits with The Impressions, “Keep on Pushing” and “People Get Ready,” released in 1964 and 1965 respectively, associate with the first phrase in the years of its great legislative victories. These songs emphasize the moral legitimacy of the movement and the religious underpinnings behind its commitment to integration and non-violent resistance.

The Impressions’ movement songs, while memorable, were a very small part of the group’s catalog. “We’re a Winner,” released in November of 1967, marks a transition. As a seeming call for black pride, it preceded by nine months James Brown’s “(Say It Loud) I’m Black and I’m Proud.” Its chorus calls more explicitly for activism than do the group’s earlier songs. During the Bitter End set, Mayfield remarks on the political blowback he’d received for the song: “You may remember reading in your Jet and Johnson publications, whole lot of stations didn’t want to play that particular recording. Can you imagine such a thing?” To this Mayfield adds a rhymed couplet, his primary lyric mode:

I would say, like I’m sure most of you would say

we don’t give a damn, we’re a winner anyway.

“Right on! Right on!” shout a number of individuals in the crowd.

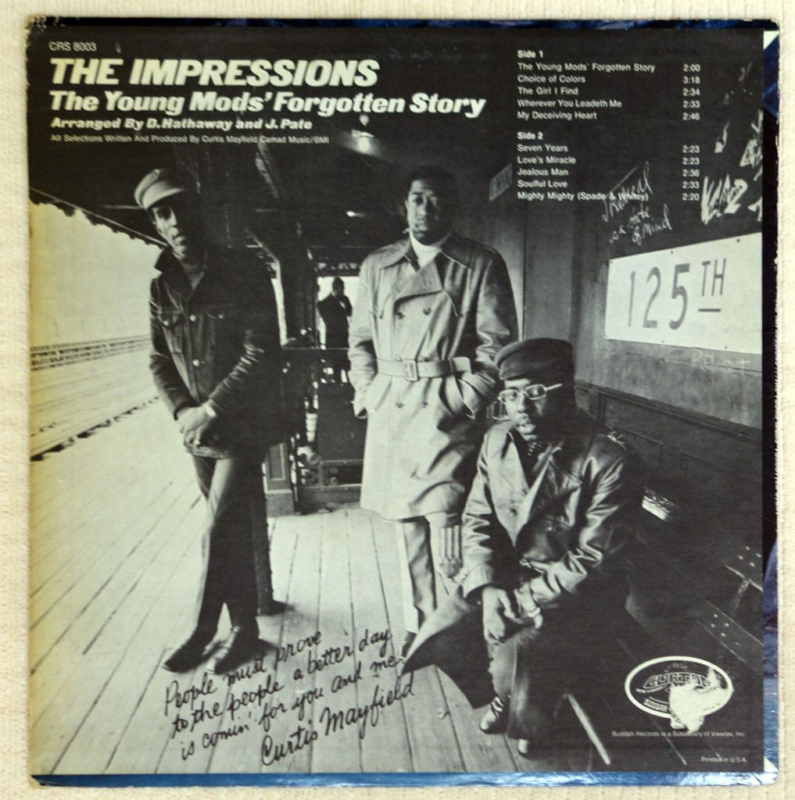

Mayfield, like any perceptive commercial artist, adjusted to the changing times. Starting with “We’re a Winner,” The Impressions’ took on a more socially conscious image and urban style. Gone was the formal, prosperous, nightclub presentation. The photo on the cover of This is My Country (1967) posed the vocal group in a crumbling cityscape; The Young Mod’s Forgotten Story

Mayfield, like any perceptive commercial artist, adjusted to the changing times. Starting with “We’re a Winner,” The Impressions’ took on a more socially conscious image and urban style. Gone was the formal, prosperous, nightclub presentation. The photo on the cover of This is My Country (1967) posed the vocal group in a crumbling cityscape; The Young Mod’s Forgotten Story

(1968) showed them again on the street, in leathers and brimmed cloth caps.

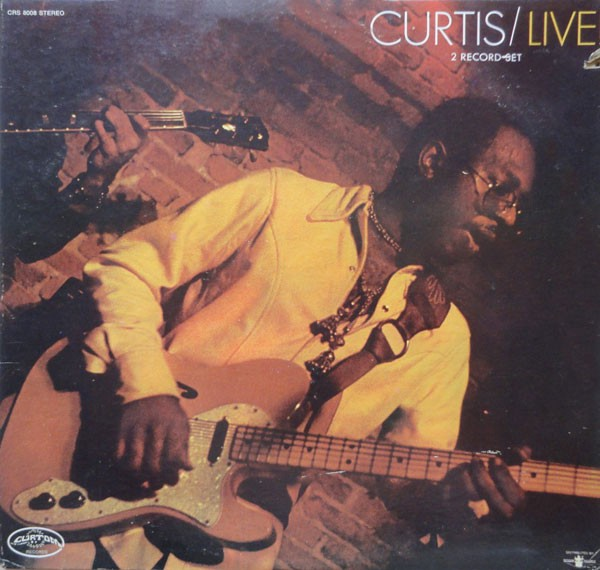

At the same time, Mayfield began a soft break from his group. Curtis/Live! was his second solo record, following Curtis in 1970, on which he continued both this stylistic and topical transition, as well as his experiments in psychedelic soul. Arrangements were complex, hand drums more prominent; he ran the guitar through a wah-wah pedal and other effects. But playing at the Bitter End, live with a small band, did not allow Mayfield the studio elaborations he’d been dabbling in. The sound was less busy, more organic. The players are wide-awake but never aggressive. They weave a warm, improvisational nest in which to hold Mayfield’s gentle falsetto. This distillation of Mayfield’s sound paved the way for his crossover triumph in 1972, the soundtrack to Superfly.

In naming adjunct components of the first phase of the Black Freedom movement, Marable includes “the deracialization of popular music.” I’m not sure I understand what he means. Interracial exchange and appropriation—love and theft—had always driven the genius of American music, though the degree of racial segregation of performance sites and the market waxed and waned. Genres are largely market-driven and racialized; they are often the tail that wags the dog. On the other hand, 1955 is a pretty good marker for the birth of rock and roll, one of the most explicitly recognized moments of love and theft. A lot of change followed in its wake, both in terms of the development of the music, and the embrace of black artists by white audiences. Music was an unmistakable cultural component of the desegregation campaign, and its contribution was simultaneous with a kind of desegregation of the popular music market. If all of these aspects are included in what Marable means by “the deracialization of popular music,” then yes, the result was an enormous cultural achievement, a vast catalog of songs and recordings that can scarcely be overpraised.

In naming adjunct components of the first phase of the Black Freedom movement, Marable includes “the deracialization of popular music.” I’m not sure I understand what he means. Interracial exchange and appropriation—love and theft—had always driven the genius of American music, though the degree of racial segregation of performance sites and the market waxed and waned. Genres are largely market-driven and racialized; they are often the tail that wags the dog. On the other hand, 1955 is a pretty good marker for the birth of rock and roll, one of the most explicitly recognized moments of love and theft. A lot of change followed in its wake, both in terms of the development of the music, and the embrace of black artists by white audiences. Music was an unmistakable cultural component of the desegregation campaign, and its contribution was simultaneous with a kind of desegregation of the popular music market. If all of these aspects are included in what Marable means by “the deracialization of popular music,” then yes, the result was an enormous cultural achievement, a vast catalog of songs and recordings that can scarcely be overpraised.

In this sense, Curtis/Live! and Superfly—along with There’s a Riot Going On (1971) and Fresh (1973) by Sly and the Family Stone, and What’s Going On (1971) by Marvin Gaye—are transitional. They are among the many jewels in the crown of this deracialization. But in them we can also see the beginning of a reversal. By the end of the decade, with a major inflection point coming with the anti-disco debacle, genres would become more racialized and politicized. Black music and white music would again be largely segregated on radio and in the marketplace.

This may have something to do with the theme of ambiguity Marable identifies in the second half of the Black Freedom movement, the struggle for Black Power. Black Power “replaced liberal integrationism as the dominant political ideology and discourse for many African Americans,” Marable writes. Yet it “never consolidated itself as a coherent social philosophy or strategy” (348). The united front of the desegregation campaign fragmented over the concept. But what did Black Power mean and what form of radicalism did it call for?

Marable indicates several “overlapping tendencies” that gathered in answer to these questions (349). Included are religious and cultural nationalisms, both of which Mayfield gestures toward lyrically on Curtis/Live! There’s the liberation gospel of “People Get Ready” and the emphasis on self-definition and solidarity in “We the People Who Are Darker Than Blue.” Marable sympathizes most with the tendency he calls revolutionary nationalism. Curtis/Live!’s most progressive sentiment may be the one expressed in “Stone Junkie,” the final cut on the record. The song points out the classist and racialized stigmatization surrounding the use of drugs and other stimulants, a critique that would become more pointed as the emerging War on Drugs took its toll.

Mayfield mostly floats atop these crosscurrents. Does he take any particular stand? Songs are different from persuasive prose. Compared to the speeches and essays that populate anthologies such as Marable’s, songs allow for much hedging and evasion. Yet in “Choice of Colors,” one of the socially conscious, late Impressions tunes that Mayfield performs on Curtis/Live!, his message is a little too slippery. The song asks a series of questions, and both their asking and their answering are never quite nailed down. It’s usually a strength that Mayfield’s rhymes don’t sound long thought-over, but in this case, the artlessness loses some of its charm.

I can only understand the song in the context of those that address the same topic, songs such as “Mighty Mighty (Spade and Whitey)” and “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Gonna Go.” On these songs, Mayfield is carrying the ideals of the first phase’s united front into the ideologically contentious second period. Mayfield has made some legitimate and productive concessions to the greater aggressiveness of Black Power and to its demands for full autonomy. I’ve mentioned the style change, and the music’s complex, improvisational space. Significant too is the greater grittiness, the cursing, and the appropriation of racial epithets for new purposes. All this points to the future. But on the question which Mayfield seemed to see as the question of the day—the question of racial separation advocated by the crosscurrents of Black Power—he upholds some form of King’s integrationist message, its spiritual core, and its insistence that the destinies of all Americans are intertwined.

0